In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United States suffered through a skyjacking epidemic that has now been largely forgotten. In his new book, The Skies Belong to Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking, Brendan I. Koerner tells the story of the chaotic age when jets were routinely commandeered by the desperate and disillusioned. These troubled souls, who hijacked nearly 160 American flights between May 1961 and January 1973, were able to create such mayhem thanks to airport security that ranged from porous to nonexistent.

In the run-up to his book’s publication on June 18, Koerner has been writing a daily series of skyjacker profiles, focusing on some of the lesser-known air pirates who made the Vietnam Era such a perilous time to fly. Slate will be running the final dozen of these “Skyjacker of the Day” entries.

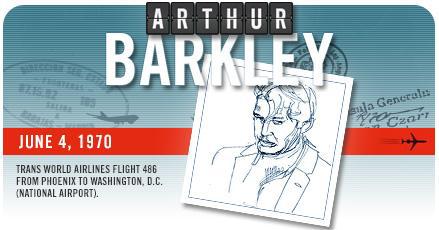

Name: Arthur Gates Barkley

Date: June 4, 1970

Flight Info: Trans World Airlines Flight 486 from Phoenix to Washington, D.C. (National Airport).

The Story: Like many of his fellow skyjackers, 49-year-old Arthur Gates Barkley was motivated by a complicated grievance against the federal government. In 1963, the World War II veteran had been fired as a truck driver for a bakery, after one of his supervisors accused him of harassment. Shortly after his dismissal, Barkley became involved in a bitter dispute with the IRS; he contended that the agency had overcharged him by $471.78 because it had miscalculated his wages. He traveled to Washington, D.C. on numerous occasions to plead his case to indifferent bureaucrats. He eventually asked the Supreme Court to hear his appeal, opening his legal brief with a memorably bombastic line: “I am being held a slave by the United States.”

When the Supreme Court declined to hear his case, Barkley resolved to take drastic action. On the morning of June 4, 1970, he kissed his wife goodbye and told her, “I’m going to settle the tax case today.”

Barkley did not undergo any sort of security screening at the Phoenix airport; TWA’s ticket agents, who were at that time solely responsible for selecting which passengers would be checked with metal detectors, did not deem him suspicious. As Flight 486 passed over Albuquerque, N.M., Barkley casually walked into the cockpit holding a .22-caliber pistol, a straight razor, and a steel can full of gasoline. He threatened to incinerate the passengers unless he was given $100 million, to be taken directly from the coffers of the Supreme Court that had ignored his plea for justice.

TWA officials were blindsided by this demand for ransom. Up until that point, American skyjackers had only been interested in obtaining passage to foreign countries, particularly Cuba. No one had envisioned a scenario in which a skyjacker might try to swap passengers for money.

With scant time to ponder the long-term implications of submitting to extortion, TWA made the fateful decision to try and mollify Barkley with money. The airline rounded up $100,750 from two banks near Dulles International Airport, where Barkley had forced the plane to land. TWA assumed that Barkley would be reasonable and settle for this lesser sum, but he was enraged at being shorted by a factor of 1,000. He poured the cash on the floor of the cockpit, ordered the plane to take off at once, and radioed back a message that he addressed directly to President Richard Nixon: “You don’t know how to count money, and you don’t even know the rules of law.”

After circling Dulles for two hours, during which time he made numerous suicidal threats, Barkley decided to give TWA one last chance to deliver his $100 million. This time the chastened airline let the FBI take charge of the situation. At Barkley’s behest, FBI agents lined the runway with a hundred mail sacks, each allegedly stuffed with $1 million. (They were actually full of newspaper scraps.) As soon as the Boeing 727 landed and rolled to a stop, marksmen shot out its landing gear. A panicked passenger reacted to the gunfire by kicking open one of the jet’s emergency exits and scrambling out over a wing; the other passengers, many of them quite inebriated after drinking for most of the hijacking, followed his lead. The FBI raided the plane moments later and engaged in a gun battle with Barkley. The hijacker was shot in his right hand during this melee, and the co-pilot was wounded in the stomach.

That night, reporters descended on Barkley’s shabby home in Phoenix, where his wife struck a defiant tone, insisting that her husband “believes in his country and the Constitution.”

The Upshot: Barkley was the first of many American skyjackers whose primary interest was money; by 1972, the majority of the nation’s hijackings would involve demands for ransom. Barkley himself was declared incompetent to stand trial in November 1971, at which point he was committed to a psychiatric hospital in Georgia.