Lifespan has doubled in the United States in the past 150 years. This ridiculously wonderful change in the nature of life and death is something we tend to take for granted. When we do think about why we’re still alive, some of the big, fairly obvious reasons that come to mind are vaccines, antibiotics, clean water, or drugs for heart disease and cancer. But the world is full of underappreciated people, innovations, and ideas that also save lives. A round of applause, please, for some of the oddball reasons, in no particular order, why people are living longer and healthier lives than ever before.

Photo by Thinkstock

Cotton. One of the major killers of human history was typhus, a bacterial disease spread by lice. It defeated Napoleon’s army; if Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture were historically accurate, it would feature less cannon fire and more munching arthropods. Wool was the clothing material of choice before cotton displaced it. Cotton is easier to clean than wool and less hospitable to body lice.

Photo by NASA via Getty Images

Satellites. In 1900, a hurricane devastated Galveston, Texas. It killed 8,000 people, making it the deadliest hurricane in U.S. history. In 2008, Hurricane Ike hit Galveston. Its winds were less powerful at landfall than those of the 1900 storm, but its storm surge was higher, and that’s usually what kills people. This time we saw it coming, thanks to a network of Earth-monitoring satellites and decades of ever-improving storm forecasting. More than 100 people died, but more than 1 million evacuated low-lying coastal areas and survived.

Fluoride. There were plenty of miserable ways to die before the mid-20th century, but dying of a tooth abscess had to be among the worst—a slow, painful infection that limits your ability to eat, causes your head to throb endlessly, and eventually colonizes the body and kills you of sepsis. Now it’s a rare way to go, thanks to modern dental care, toothbrushes, and (unless you’re in Portland) fluoridated water.

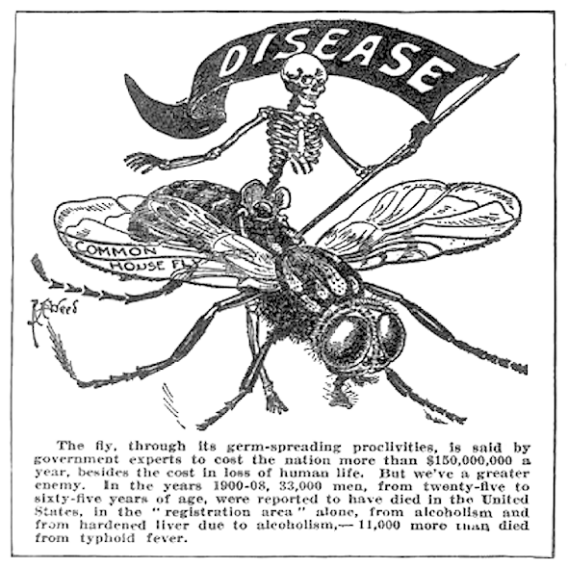

Image courtesy Library of Congress

Window screens. Houseflies are irritating today, but they used to be major vectors of deadly diarrheal disease. Clean water and treatment of sewage eliminated the most obvious means of transmitting these diseases, but pesky houseflies continued to spread deadly microbes. By the 1920s, according to James Riley in Rising Life Expectancy: A Global History, a growing aversion to insects and the introduction of window screens reduced this risk.

The discovery of unconscious bias. The reason we trust double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials to tell us which medical treatments actually work is that we know we can’t trust ourselves. If you take a sham drug that you think will alleviate your symptoms, it will—that’s the placebo effect. If you think the drug will cause side effects, it will—that’s the nocebo effect. If you’re a clinician and think you’re administering a real drug, you will send all kinds of signals, unintentionally, to tell the patient you think the treatment will work. If you’ve seen anecdotal evidence for a treatment, you notice confirmatory evidence rather than cases that make you revise your original hypothesis. When analyzing the data, it’s all too easy to squint at the numbers in a way that confirms your expectations. Double-blind trials overcome these biases by preventing both patient and clinician from knowing whether a tested drug is real or not.

Photo courtesy Frank Chan/Flickr via Creative Commons: http://www.flickr.com/photos/geekstinkbreath/5767003752/

Botts’ Dots. Those raised ceramic reflectors between road lanes were invented by Elbert Botts, a chemist who worked for the California Department of Transportation. The dots help motorists see the edge of their lane even in the dark or when it’s raining. Botts died in 1962, four years before the first Botts’ dots were installed on California highways.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. That’s the no-nonsense name of one of the most important publications most people have never heard of. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been publishing it since 1952 to provide “timely, reliable, authoritative, accurate, objective, and useful public health information and recommendations.” When a new disease or danger emerges—such as AIDS or a new strain of influenza—the MMWR is often the first to identify it.

Air-conditioning. As Dan Engber pointed out in a two-part ode to A/C last summer, heat is deadly and we don’t respect it enough. A Chicago heat wave killed more than 700 people in one week in 1995. The National Weather Service issues heat alerts, and cities have started to offer air-conditioned cooling centers for people who would overheat at home. A recent study shows that air conditioning has cut the death rate on hot days by 80 percent since 1960.

The residents of Framingham, Mass. In 1948, researchers signed up more than 5,000 adults for a long-term study of heart disease. Nobody anticipated just how long-term the study would be—it’s still going strong and now includes the children and grandchildren of the original cohort. It taught us much of what we know about heart disease. Before the study, high blood pressure was thought to be a sign of good health; now it’s recognized as a risk factor for heart attacks and strokes. Thanks to the generosity and commitment of volunteers in Framingham and other studies, we know the dangers of high cholesterol, obesity, inactivity, and smoking.

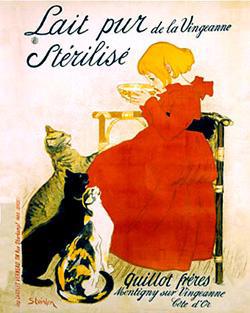

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Pasteurization. This should be an obvious lifesaver, right up there with hand-washing and proper nutrition. But the rise of the raw milk movement suggests that a lot of people take safe dairy products for granted. Contaminated milk was one of the major killers of children, transmitting typhoid fever, scarlet fever, diphtheria, tuberculosis, and other diseases. One of the most successful public health campaigns of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was for pure and pasteurized milk—so successful that we don’t really remember how deadly milk can be.

Shoes. Hookworms are parasites that enter the human body through bare feet—often by biting into the soft skin between the toes (shudder). The disease was common in the Southeast, spread when people walked barefoot across ground that was contaminated with feces of people who were already infected. Education initiatives at the beginning of the 20th century encouraged people to build sanitary outhouses and wear shoes.

Cows. I mentioned in an earlier story that the Midwest—including Michigan!—once had some of the worst malaria outbreaks in the country. Anopheles mosquitoes had always flourished in the damp lowlands around streams and melting snow, and when settlers came, some of them carried Plasmodium parasites that the mosquitoes spread widely. The settlers’ farming practices made for even more stagnant water, and their sod and log houses were perfect habitat for biting pests. After farmers had exhausted the soil, they started raising cows rather than crops—and mosquitoes prefer to suck bovine blood even more than that of humans, helping break the malaria cycle. In the South and other parts of the country, larvicides, pesticides, better drainage, bug-proof housing, mechanized agriculture that replaced human labor, and fewer people living in lowlands helped eliminate malaria.

Image courtesy CDC via Wikimedia Commons

Oppressive, burdensome, over-reaching government regulations. People like to complain about the government, but when you start looking through the alphabet soup of agencies, you realize that most of them are there to save your life. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration runs the National Weather Service and warns you about hurricanes. The Environmental Protection Agency enforces the Clean Air Act and has dramatically reduced the amount of deadly pollutants in the air you breathe. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration keeps you safe at work. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and National Transportation Safety Board investigate vehicles and accidents and make recommendations so accidents don’t happen again. The Food and Drug Administration keeps deadly microbes out of your food. The Consumer Product Safety Commission recalls toys that could kill your child. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks and tries to cure or avert basically any health hazard, and the National Institutes of Health supports some of the most important biomedical research in the world.

Goodness. Philosopher Daniel Dennett had an epiphany after emergency surgery a few years ago. It wasn’t a religious epiphany—instead of thanking God, he realized he should thank human goodness:

“To whom, then, do I owe a debt of gratitude? To the cardiologist who has kept me alive and ticking for years … the surgeons, neurologists, anesthesiologists, and the perfusionist, who kept my systems going for many hours under daunting circumstances. To the dozen or so physician assistants, and to nurses and physical therapists and x-ray technicians and a small army of phlebotomists so deft that you hardly know they are drawing your blood, and the people who brought the meals, kept my room clean. … I remember with gratitude my late friend and Tufts colleague, physicist Allan Cormack, who shared the Nobel Prize for his invention of the CT scanner. Allan—you have posthumously saved yet another life, but who’s counting? The world is better for the work you did. Thank goodness. Then there is the whole system of medicine, both the science and the technology. … So I am grateful to the editorial boards and referees, past and present, of Science, Nature, Journal of the American Medical Association, Lancet, and all the other institutions of science and medicine that keep churning out improvements, detecting and correcting flaws.”

These are just a few of the countless ways people have made life safer, healthier, less painful—and longer—than we ever could have imagined a few centuries ago. Thank goodness.

Read the rest of Laura Helmuth’s series on longevity.