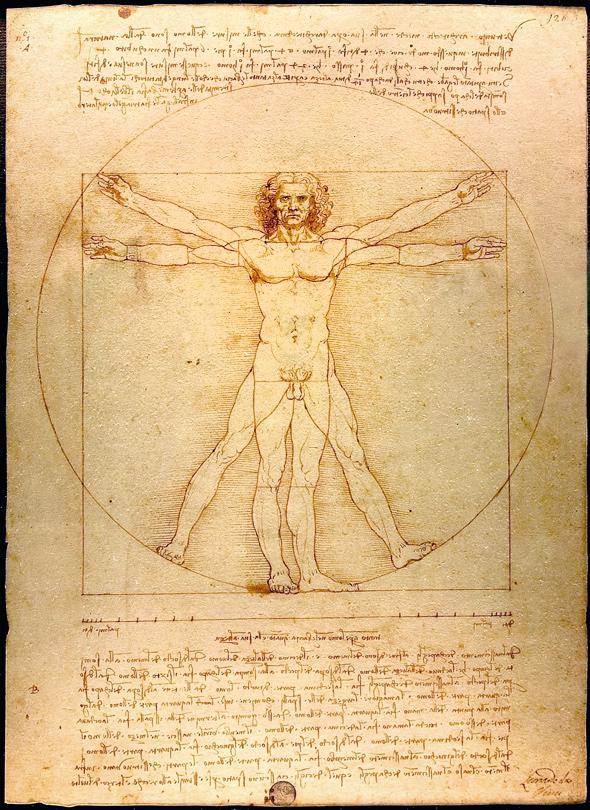

Around the year 1487, Leonardo da Vinci sketched what would become one of the most famous illustrations in the world. In it, a perfectly drawn circle sits atop a square. Perfectly framed within those shapes, with arms and legs outstretched in two different orientations, is a curly-haired, slightly frowning, and very naked man now commonly known as “Vitruvian Man.”

Perhaps no piece of art illustrates the beauty of the human body better than Vitruvian Man. Leonardo obsessed over the perfect proportionality of the human body. He pored over the calculations of the Roman architect Vitruvius, who had labored in the 1st century B.C. to describe the beauty of human proportions. In Book III of his treatise De Architectura, Vitruvius wrote:

For if a man be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centered at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square figure may be found from it.

Depicting the human form in this way expressed Leonardo’s belief that humankind represented a microcosm of the universe. Fitting within a circle, humans were a reflection of the celestial. Fitting within a square, humans were also a reflection of the Earth. By inhabiting both shapes, symbolizing different aspects of the universe, humans could bridge the gap between the terrestrial and the divine. As Leonardo wrote in a notebook entry dated to around 1492:

By the ancients man has been called the world in miniature; and certainly this name is well bestowed, because, inasmuch as man is composed of earth, water, air and fire, his body resembles that of the earth.

But there’s a bump in the story. In 2011, Hutan Ashrafian, a lecturer of surgery at Imperial College London, noticed an odd thing about Vitruvian Man. You can be forgiven for not gazing much at Vitruvian Man’s package. But not everyone has been so modest, and while looking at Leonardo’s illustration, Ashrafian noticed an odd bulge near Vitruvian Man’s bulge. This protuberance, slightly above the left side of his groin, looks exactly like a medical problem that plagues about 30 percent of men and 3 percent of women in their lifetimes: an inguinal hernia.

Throughout history, anatomical illustrations have been made using the recently deceased as models, and many of Leonardo’s sketches were no exception. Ashrafian says that the man who served as Leonardo’s model for his illustration of human perfection probably had a hernia. If the model was a corpse, the hernia may have been what killed him. If he was a live model, he may ultimately have died from its complications. Other experts agree with Ashrafian, including Jeffrey Young, director at the University of Virginia’s Trauma Center, and Michael Rosen, director of the Comprehensive Hernia Center at University Hospitals Case Medical Center. “If it isn’t a hernia,” says Rosen, “then I really have no idea what it would be.”

The possibility that Vitruvian Man had a hernia is just that, a possibility. “The cool thing with art is it is all in the eye of the beholder,” says Peter Hallowell, director of bariatric surgery at the University of Virginia. If you squint, tilt your head, and look closely at his groin, you might be able to see what the fuss is about. But if you’ll indulge me, the significance of Vitruvian Man now becomes all the more profound. It illustrates not just Renaissance ideas of our place in the universe, but it also takes us down a labyrinthine path deep into humans’ evolutionary history.

Vitruvian Man c. 1492.

Leonardo da Vinci/Accademia of Venice

Humans, along with killer whales, deer, and pangolins, are mammals. Our fuzzy, milk-producing lineage evolved about 225 million years ago from reptilian ancestors. For reasons that remain obscure, male mammals usually have their man-parts swinging out in the breeze instead of snuggled comfortably within their bodies.

As a male mammalian fetus develops, his testicles start near the kidneys, and over the course of several weeks take a meandering trip through the inguinal canals before finally being pushed through the abdominal wall to their final resting spot in the scrotum. Females’ reproductive organ development is slightly less complicated, but also involves a passage through the inguinal canals.

Because this process compromises our lower abdominal tissue, our intestines have only a flimsy tissue layer supporting them inside of our body cavity. This isn’t much of a problem for most mammals because they get around on four legs, with their bodies positioned in such a way that the stomach muscles support the weight of the intestines.

But in the human lineage, which has been walking upright for a little longer than 4 million years, the weak layers of lower abdominal wall tissue must bear the brunt of our intestinal weight. When a bit of intestine bulges through a thin layer of lower abdominal tissue, a hernia is born.

Humans have mused about the origins and relationships of living creatures for millennia. But it wasn’t until Charles Darwin that we figured out how evolution produces structures as elegant as the eye, as bizarre as the proboscis of a butterfly. Natural selection, often described tautologically as “the survival of the fittest,” is the process that allows a new mutation—say the ability to digest lactose in dairy products—to persist and spread through members of a species across generations.

Evolution by natural selection is an unconscious process, but it is often described metaphorically as being like a tinkerer, messily working away with odds and ends that are already lying around, with no grand plan in sight. Because natural selection can only work with what already exists, evolution can’t simply take apart faulty structures and rebuild them from the ground up. It is stuck with what’s around and must make the best of it.

This means many of the traits found in our bodies are effectively jury-rigged. These imperfect traits work well enough most of the time, but when we look closely we can see chinks in our armor. Case in point: Natural selection has tinkered with the four-legged mammalian body plan to make the human two-legged plan. It lets us tap dance and high five, but hernias are just one of many problems that arose as a byproduct when we began walking upright.

Full-time two-legged walking demanded skeletal changes from head to toe. The spine of our four-legged mammalian cousins forms an arch. Our spines serve as weight-bearing structures for our entire body, and they have adopted some wavy S-shapes to do so. Our feet developed an arch. Our pelvis widened and flattened into a saddle shape.

All of the evolutionary changes to our skeletal structure put pressure on the delicate joints of our lower spine, our pelvises, and our feet, causing frustrating health issues like pinched nerves, fallen arches, and the back and neck pain that plague so many of us. Changes to the shape of our pelvises also explain why childbirth is such a dangerous endeavor for women, often requiring a phalanx of helpers.

And these are just issues that arose when we began walking on two legs. If we explore other adaptations from our evolutionary past, we can find explanations for why laughing while eating is a dangerous pastime, why we should all suffer from octopus eyeball envy, and why you might react just fine to blood thinners while I react adversely.

Leonardo da Vinci created a piece of art more elegant and profound than he knew when he sketched the Vitruvian Man. In the half-millennium since his death, we have learned that humans (and all living creatures) do indeed bridge the gap between the terrestrial and the celestial. Most of the buzzing atoms that make up our bodies have called our planet home since our solar system formed in a great swirling gaseous mass more than 4.5 billion years ago. These atoms have even loftier origins, born in the violent deaths of the universe’s early stars.

But in selecting his model for human perfection, Leonardo also managed to depict how our perfect bodies, upon closer inspection, are never so perfect after all. His sketch also reminds us that there is a certain futility in humans’ historic search for an exemplar, the one individual we can all point to and call the pinnacle of the human form. Unlike Leonardo’s neo-Platonic ideals, there are no archetypes in biology, beyond those we hold in our own minds.

Vitruvian Man simultaneously displays the elegance of our body and the deep-seated imperfections and old-fashioned workarounds that we inherited from our ancestors over the course of 3.8 billion years of life on Earth. Through him, we can tell parallel stories: the story of the evolution of our bodies, and that of the evolution of our understanding of the universe.

He allows us to marvel at how the universe and its natural laws, working through such an imperfect, iterative process as evolution, could produce an organism as curious, intelligent, and self-reflective as Homo sapiens. A hairy, awkward, sometimes violent, sometimes peaceful creature who can gaze up at the sky and ask: Who am I, and why am I here?