Read the rest of Laura Helmuth’s series on longevity.

The best person I know almost died in childbirth. We met during college when we both volunteered at a commune in Georgia, the place Habitat for Humanity grew out of. Being a do-gooder was an anomaly for me, but it’s how Gwen has spent her life—she’s wise and kind and generous. She works in a mental health agency for HIV-positive people. When she was seven months pregnant, her diaphragm, the band of muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen, split, and a piece of stomach pushed up through it and necrotized. She went into labor, gave birth to her daughter, and had emergency surgery followed by massive doses of antibiotics. If this had happened even a few decades ago, she and the baby would both be dead. Instead, she’s fine, and her daughter is a wise, kind, generous child who wants to be a scientist.

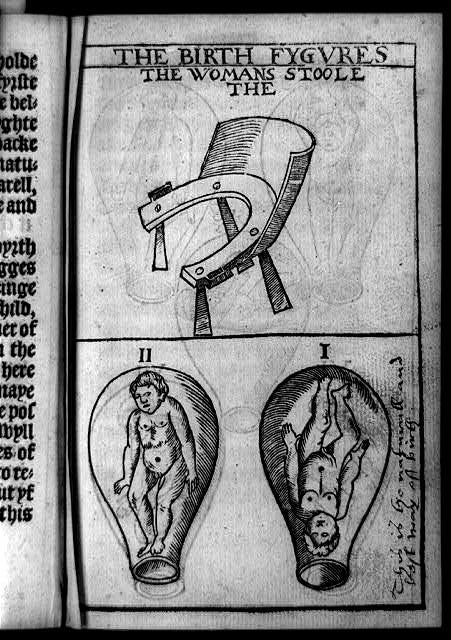

Courtesy of Thomas Raynalde/Tradition of Science/Leonard C. Bruno/Library of Congress

Bearing a child is still one of the most dangerous things a woman can do. It’s the sixth most common cause of death among women age 20 to 34 in the United States. If you look at the black-box warning on a packet of birth control pills, you’ll notice that at most ages the risk of death from taking the pills is less than if you don’t take them—that’s because they’re so good at preventing pregnancy, and pregnancy kills. The risk flips only after age 35 because birth control pills increase the risk of stroke. (Psst, guys, you know what makes an excellent 35th birthday present for your partner? Getting a vasectomy.)

In the United States today, about 15 women die in pregnancy or childbirth per 100,000 live births. That’s way too many, but a century ago it was more than 600 women per 100,000 births. In the 1600s and 1700s, the death rate was twice that: By some estimates, between 1 and 1.5 percent of women giving birth died. Note that the rate is per birth, so the lifetime risk of dying in childbirth was much higher, perhaps 4 percent.

Evolutionarily, childbirth seems like an exceptionally bad time to die. If by definition the ultimate measure of evolutionary success is reproducing successfully, the fact that women and newborns frequently died in childbirth suggests that powerful selective forces must be at work. Why is childbirth such an ordeal?

Compared to other primates, human infants are born ridiculously underdeveloped; they can’t do much more than suck and scream. They would be better off if they could gestate longer—but the mother wouldn’t be. The classic explanation for why human infants are born at such an early stage of development has to do with anatomical limits on women’s hips. If the fetal head had time to grow any larger in utero, the baby wouldn’t fit through the pelvic girdle. And the pelvic girdle can’t get any wider or women wouldn’t be able to walk efficiently.

This is called the “obstetric dilemma” hypothesis and it’s been dominant for years, but it’s almost certainly wrong, or at least not the full story. Anthropologist Holly Dunsworth and her colleagues found that broadening the pelvis wouldn’t actually interfere with walking, and they point out that gestation is actually pretty long in humans compared to other primates (even though newborns’ brains are relatively less developed). Other researchers suggest that the problem of “obstructed labor”—when a baby basically gets stuck in the birth canal—seems to have become common fairly recently in human history.

The real reason women give birth when they do, Dunsworth says, is that it would take too much energy to feed a fetus for any longer. This is the “metabolic hypothesis” and it’s based on the finding that the maximum metabolic rate people can sustain is about 2 or 2.5 times their standard rate of using energy. During the third trimester, that’s exactly how much metabolic activity the pregnancy demands. Carrying a fetus for those final few months “is like being an incredibly good athlete,” Dunsworth says. No wonder it’s so exhausting.

* * *

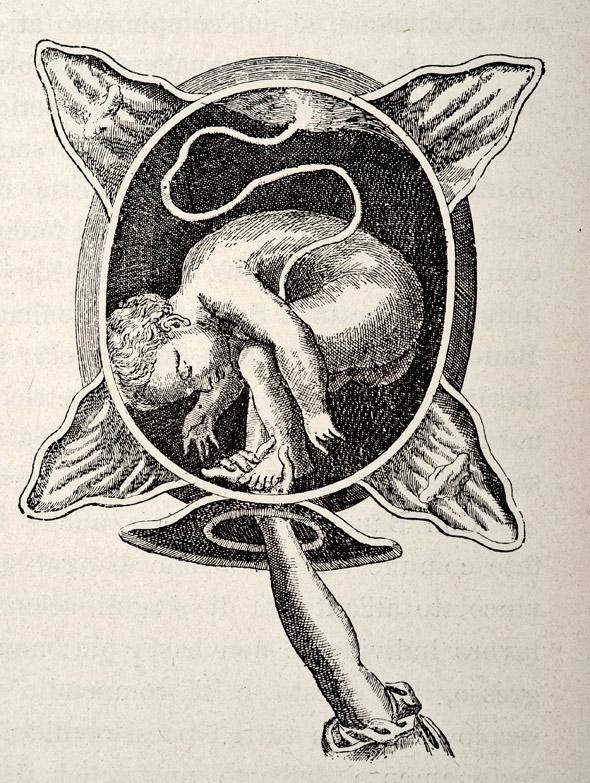

Photo by VintageMedStock/Getty Images

By the late stages of pregnancy and during childbirth, almost anything can go wrong. Pregnant women are sapped of energy. They are susceptible to infectious disease. The baby’s head is enormous. Labor takes much longer in humans than in other primates; women often pushed for days. Historically, women died of puerperal fever (also called childbed fever, or postpartum sepsis, an infection usually contracted during childbirth), hemorrhage, eclampsia (dangerously high blood pressure and organ damage; that’s what killed Sybil on Downton Abbey), and obstructed labor.

Given all the dangers, how did deaths in childbirth fall to about one-fiftieth of the historic rate? Life expectancy in the United States and the developed world basically doubled in the past 150 years, and a decrease in maternal mortality is ultimately a big reason for our longer, healthier lives. But the history of childbirth death rates is complicated and disturbing. It’s a story of hubris, mistrust, greed, incompetence, and turf battles that live on today.

The death rate in the overall population started dropping at the end of the 1800s, and it dropped most dramatically during the first few decades of the 20th century. Childbirth deaths were different. They actually increased during the first few decades of the 20th century. Even though pregnant women had less exposure to disease and were more likely to have clean water, proper nutrition, safe food, and comfortable housing than at any previous time in human history, they died in droves in childbed.

It was doctors’ fault.

For most of European and U.S. history, midwives had attended births. Some were incompetent, some were skilled. The best ones wrote and read reports on techniques and treatments, and there’s some evidence they were becoming better trained and having better outcomes during the early 1800s. Doctors had little to do with childbirth—they were all men, and it was considered obscene for a man to be present at a birth.

As the profession of medicine grew during the 1800s, though, doctors started to edge their way into the potentially lucrative business of childbirth. The first ones were general practitioners who had no training and little experience in childbirth. It was considered a low-status specialty and wasn’t taught well or at all in most medical schools.

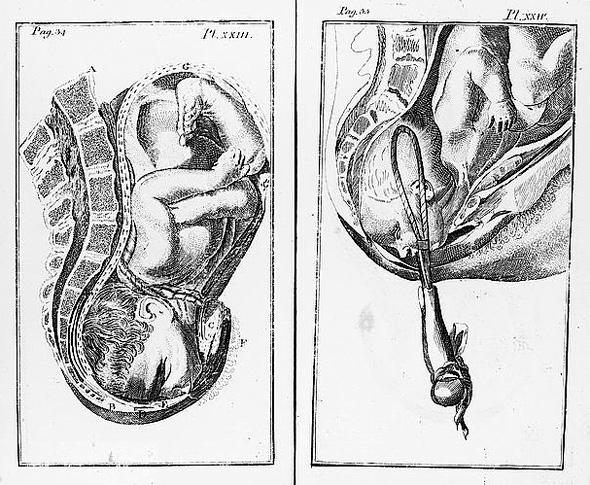

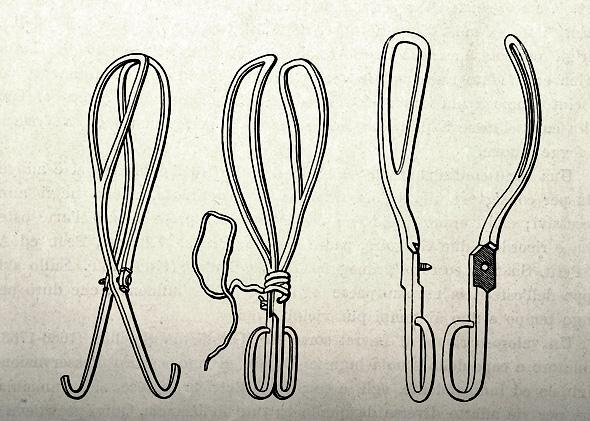

Courtesy of William Smellie and John Norman/Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division

In the delightfully named book Get Me Out: A History of Childbirth from the Garden of Eden to the Sperm Bank, Randi Hutter Epstein describes the state-of-art treatment: “Before forceps, babies stuck in the birth canal were dragged out by the doctor, often in pieces. Sometimes midwives cracked the skull, killing the newborn but sparing the mother. Sometimes doctors broke the pubic bone, which often killed the mother but spared the baby. Doctors had an entire armamentarium of gruesome gadgets to hook, stab, and rip apart a hard-to-deliver baby. Many of these gadgets had an uncanny resemblance to medieval torture tools.”

Photo by VintageMedStock/Getty Images

The biggest danger to expectant mothers was infection. Before the germ theory of disease, people suspected puerperal fever could somehow be contagious, and they knew that some midwives and doctors had worse records than others, but no one knew how it was transmitted. (“Putrid air” was one popular hypothesis.) To avoid blame for maternal deaths, doctors lied on death certificates—they’d attribute a new mother’s death to “fever” rather than “puerperal fever” or mention hemorrhage without mentioning that the hemorrhage was caused by childbirth.

In the mid-1800s, Ignaz Semmelweis discovered that doctors in his hospital in Vienna were spreading puerperal fever when they went directly from performing autopsies to delivering babies—but his work was mostly ignored. There were many reasons for this: He was apparently a real pill, the methods he suggested for sanitizing the hands were caustic and difficult, and most doctors attending births at home hadn’t been near a corpse. Doctors were also offended by the accusation that their filth was responsible for deadly disease: Gentlemen didn’t have dirty hands.

The best source of historic information on this subject is a book called Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality 1800-1950, by Irvine Loudon. (If you are pregnant, whatever you do, do not read this book.) It’s a very serious work, rich in data and graphs and analysis, but you can tell he’s furious about all the unnecessary deaths at the beginning of the 20th century. Here’s how he described puerperal fever: “A woman could be delivered on Monday, happy and well with her newborn baby on Tuesday, feverish and ill by Wednesday evening, delirious and in agony with peritonitis on Thursday, and dead on Friday or Saturday.” During the 1920s in the United States, half of maternal deaths were caused by puerperal fever. For a disease that was “preventable by ordinary intelligence and careful training,” he wrote, “these figures were a reproach to civilized nations.”

One piece of evidence Loudon uses to attribute blame for unnecessary early 20th century deaths to doctors is that rich women were more likely to die in childbirth than poor women. (Mary Wollstonecraft was one victim of an incompetent doctor; she died of puerperal fever after delivering a daughter who would grow up to write Frankenstein.) For almost any other cause of death, the poor were more likely to die than the rich. But for childbirth, poor women could afford only midwives. Rich women could afford doctors. Doctors in turn had to justify their fees and distinguish themselves from lowly midwives by providing new tools and techniques.

Things got worse as obstetricians started professionalizing and coming up with new ways to treat—and often inadvertently kill—their patients. Forceps, episiotomies, anesthesia, and deep sedation were overused. Cesarean sections became more common and did occasionally save women who would have died of obstructed labor, but often the mother died of blood loss or infection. (Fun fact: Julius Caesar wasn’t born of a C-section. As Hutter Epstein points out in Get Me Out, until recently the technique was used to extract a baby from a dying woman. “Cesarean sections were death rituals, not lifesaving procedures. If a doctor suggested a cesarean, you knew you were on the way to the morgue.”) Women giving birth in hospitals were at greater risk than those delivering at home. Disease and infections spread more readily in hospitals, and doctors were all too eager to use surgical equipment.

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Too many doctors and midwives were chasing after a limited number of pregnant women, and they gained market share by touting dazzling new techniques and bad-mouthing their competitors. Exacerbating the problem, there was little government oversight of medical care or education in the early part of the 20th century. As Loudon explains, “Medical care in the United States was dominated by the belief in the virtues of competitive free enterprise combined with an intense distrust of government interference.”

“If I was forced to identify one factor above all others as the determinant of high maternal mortality in the USA,” Loudon wrote in Death in Childbirth, “I would unhesitatingly choose the standard of obstetric training in the medical schools.” They instilled an attitude of carelessness, impatience, and unnecessary interference. These deaths were “a blot for which the leaders of the medical profession are wholly to blame.”

* * *

Death rates in childbirth finally began to drop in the 1930s with the introduction of sulfa antibiotics that were highly effective against the streptococcal bacteria responsible for most cases of puerperal fever.

Doctors cleaned up their acts, too. A series of reports in the 1940s linked high death rates to improper medical procedures. Training improved, and doctors abandoned the most dangerous techniques. Complications from C-sections declined steadily. Medical researchers now rigorously evaluate success rates and risks of new techniques and drugs.

As nutrition improved, there were fewer women with rickets, which causes bone deformations; many obstructed births in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were caused by abnormal pelvic bones in the mother. Prenatal care became a standard part of medical practice.

Reliable, safe, and legal birth control allowed women to limit and time their pregnancies, and it led to a decrease in illegal abortions, a leading cause of death in pregnant women historically.

Improved maternal survival eventually did turn into one of the great public health and medical achievements of the 20th century—it just took an unconscionably long time. The good news today is that, globally, maternal mortality is continuing to decrease. More women are surviving childbirth, and that’s a big reason—and one of the most joyful reasons—why lifespan is continuing to climb in the 21st century.

* * *

The midwives and doctors, though—they’re still tangling. Midwives accuse doctors of endangering women by continuing to perform too many unnecessary procedures. Doctors accuse midwives of allowing pregnant women and newborns to die of preventable deaths.

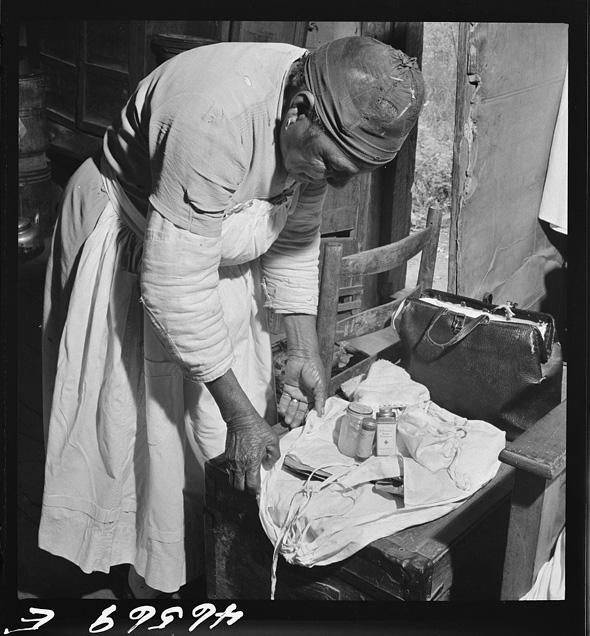

Courtesy of U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information/Library of Congress

The main battlefield today is over home births. About 1 percent of women in the United States choose to give birth at home. Counterintuitive as it may sound at first, they often cite safety concerns—they’re worried about unnecessary procedures if they give birth in a hospital. And they “trust their bodies’ inherent ability to give birth without interference.” Melissa Cheyney is an anthropologist at Oregon State University as well as a home-birth advocate and midwife. She reports that women who choose home birth “value alternative and more embodied or intuitive ways of knowing.” Home-birth advocates say women are better off giving birth in a comfortable environment, letting nature take its course.

I’m personally opposed to letting nature take its course—nature will kill you. And “intuitive ways of knowing” is just a flowery term for “ignorance.”

A meta-analysis of outcomes from home births and hospital births shows that women who give birth at home do have fewer procedures and complications—but their newborns are three times more likely to die. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advises that hospitals and birthing centers are the safest places to give birth, and they have published guidelines for how to talk pregnant women out of a home birth. Many states are considering or tightening restrictions on midwives and home births, including Idaho, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Indiana, often in response to heartbreaking and infuriating cases of women or infants dying due to incompetent treatment.

But it turns out home birth isn’t as clearly dangerous as I expected. The Cochrane Collaboration, a highly respected organization that carefully judges medical treatments, analyzed the available evidence—which is admittedly a bit of a mess. (Among other problems, if a home birth delivery goes wrong, the woman has to be rushed to the hospital, where the complicated case may be recorded as a hospital birth rather than a home birth.) But the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that planned home births with low-risk mothers are as safe as hospital births. Once more for emphasis, though: This is only for women who have an extremely low chance of complications and who have access to emergency medical treatment if anything goes wrong. It’s tricky to compare outcomes across countries—especially because licensing and training regulations differ—but a Canadian study showed that home births were safe. (In the United States there are two main types of midwives: registered nurses who specialize in midwifery and are highly medically trained, and certified professional midwives, whose training may be, ah, less medically rigorous.)

The conflict between doctors and midwives puts pregnant women in the middle and can be uncomfortable and dangerous in itself. And it turns both sides into caricatures of themselves. Doctors focus on risks and complications; midwives focus on a pregnant woman’s comfort. Midwives talk about intuition and say pregnancy is the most natural thing in the world. They accuse doctors of lacking empathy—which isn’t surprising since medical students get a lot of empathy squeezed out of them during their training.

For individual simple, low-risk births, having a home birth overseen by a highly trained midwife isn’t necessarily a clearly terrible decision. But when you take a world-historical look at childbirth, it’s not midwives and cozy home births that get credit for making maternal death such an unthinkable outcome today. One of the great victories of modern times is that childbirth doesn’t need to be natural, and neither does the maternal death rate. It’s modern medicine for the win. Doctors may have killed a lot of women in the first part of the 20th century, but they can save your life today.

Read the rest of Laura Helmuth’s series on longevity.