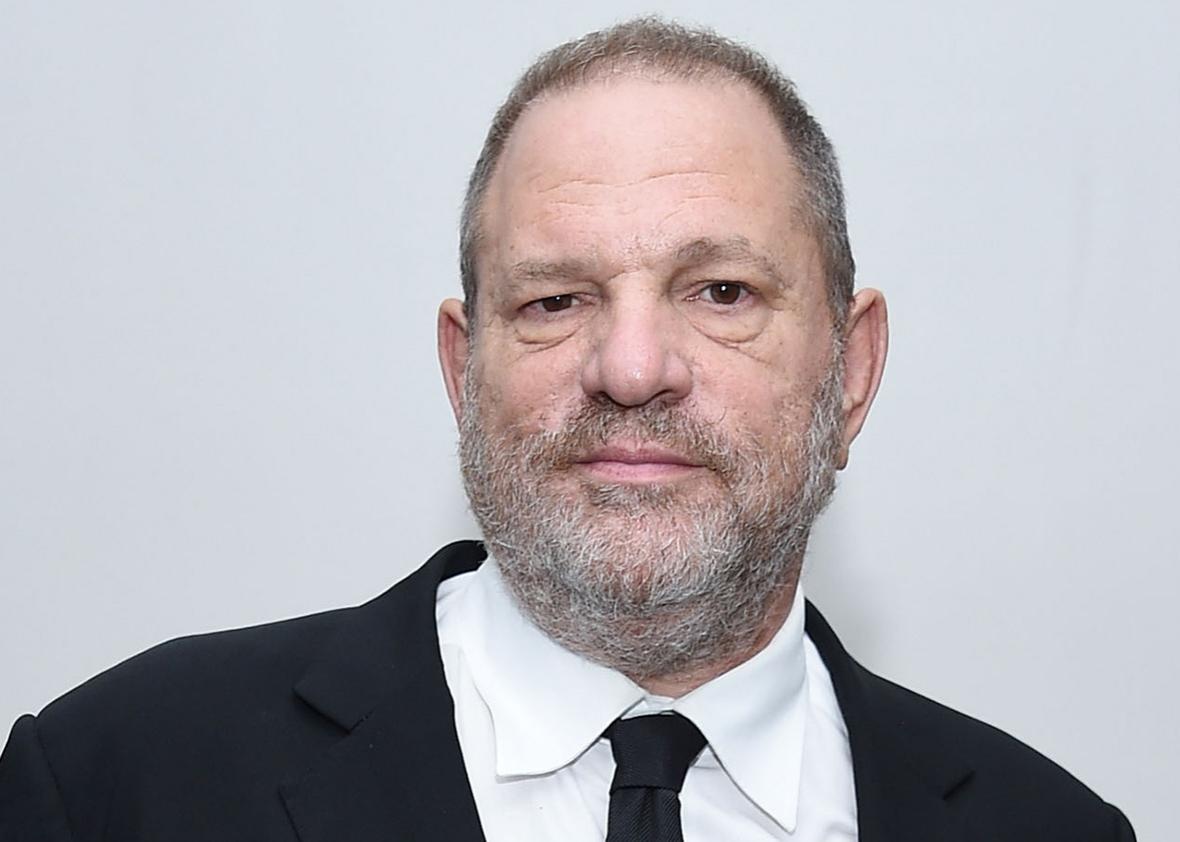

Harvey Weinstein set off on his private jet to Europe on Tuesday night, where he intends to enter a rehab facility for sex addictions, according to TMZ. The escape, which came after mounting allegations of sexual harassment and assault from A-listers including Gwyneth Paltrow and Angelina Jolie, and removal from his company, is a progression on his assertion last week that, with a team of therapists he had brought on, he would take a leave of absence from his company and use his time to “conquer [his] demons.”

Last week, after the New York Times’ first report about his misconduct, the idea that Weinstein’s “punishment” would be hours and hours of “counseling” was simply another frustrating manifestation of the extreme privilege given to powerful men like him. This week, after it became apparent that Weinstein’s pattern of sexual misconduct included sexual assaults, the idea that Weinstein gets to deflect these accusations with But I’m a sex addict! feels downright absurd. Sadly, though, it’s not surprising. “This is a very typical psychological defense of people who are initially discovered or caught or held accountable,” said Douglas Braun-Harvey, a sex educator and counselor. “That’s one of the great appeals of the addiction model—it provides the person something outside of themselves to initially place responsibility. It’s very common.”

It’s also, frankly, a bad excuse. As psychologist and sex therapist David Lee put it, “sex addiction is a moralistic pseudoscience that is used to excuse the selfish behaviors of those who hold sexual privilege, in order to protect them from the consequences of their choices.” There is no formal diagnosis for “sex addiction.” It is not listed in the “bible” of the American Psychiatric Association, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM V), and in December, the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists crafted a statement to clarify its position that sex addition is not clinically meaningful. “AASECT 1) does not find sufficient empirical evidence to support the classification of sex addiction or porn addiction as a mental health disorder, and 2) does not find the sexual addiction training and treatment methods and educational pedagogies to be adequately informed by accurate human sexuality knowledge,” the organization wrote. There are, of course, people who have problems with sexual compulsions, and there is indeed debate within the profession on the AASECT’s position, but the sex therapists that I spoke with agree that it is not a useful diagnosis—particularly when it is used as a get-out-of-jail-free card for behavior that is harmful to others.

Which brings us to the real issue when it comes to Weinstein. The problem is not that Weinstein was having sex with too many people, and that he tried to stop himself and found that he couldn’t—something you might expect from someone struggling with addiction. The problem is that he abused his position of influence and forced many, many women to subject themselves to sexual acts that were obviously nonconsensual or, more complicatedly, could never be truly consensual. And nonconsensual sex is psychologically very harmful—it’s a “violation of human behavior,” as Braun-Harvey put it.

What would cause someone to continuously engage in nonconsensual sex? “This type of sexual violence isn’t about sex. It’s about power,” Samantha Manewitz, a certified sex therapist who specializes in sexual trauma, told me. And there are all kinds of reasons why someone would abuse power. Indeed, the remarkable thing about the Weinstein case is not the form his abuse of power took—people frequently act out their power struggles through sexually problematic behavior. The remarkable thing is how protected he was from consequences. “This behavior is going on every day all the time,” Braun-Harvey said. “When a very visible person does it, we make the error of thinking it’s done by people of power. But this is not an uncommon human behavior—people who are in positions of power just have more avenues to get away with it, and that repulses us as a society.”

Other people may not have had unlimited access to hotel rooms and settlement cash. Other people may not have had such ease luring victims. Other people may not have had the same potential rewards to offer. Weinstein did, and that enabled him to carry on for such a long time that now the list of victims is in the dozens and includes a few of the most powerful women in Hollywood. That is shocking, and that draws back the curtain on an aspect of our human behavior that is difficult to reconcile, and deserves serious attention.

That shock can lead people to believe that these destructive compulsions are unusual. It’s easy to think that there are some monsters like Harvey Weinstein, and if we remove them from society, then we will be safe. This type of thinking is understandable, but it’s primarily a defense mechanism, of sorts. It allows us to classify these kinds of actions as aberrations when in fact they are a part of the human condition, and something we must constantly guard against—in others and in ourselves.

Both Manewitz and Braun-Harvey acknowledged that there are psychological treatments available for people who have abused and harmed others. Indeed, given the commonness of the action, it would be horrifying to think there might not be. “You have to separate the person from the behavior,” Manewitz said. “You can be a good person and inflict harm. So the question isn’t if you’re a bad person. It’s if you inflicted harm, and how are you going to change that behavior.”

Braun-Harvey, who helped write AASECT’s statement about sex addiction, noted that it is possible for people who have participated in nonconsensual behavior to seek counseling, and that some therapists work specifically in this area, though it is separate from “sex addiction rehab.” But just because the counseling exists does not mean it will work in every case. “I have given up trying to predict how people will respond and who might change and who might not,” he said. “There’s no way of knowing, and that’s the difficult part to accept.”

Even if Weinstein were serious about therapy, that would not absolve him in any way of his crimes—and they are crimes. He abused women for decades, and he should have to answer for the harm he caused regardless of whatever psychological demons compelled him to do it. It seems unlikely, however, that he will actually be brought to justice: One of the more depressing revelations of this week has been the realization that even the woman who went straight to the police could not hold him accountable.

The law likely won’t force accountability on Weinstein. At least in this case, society is trying to make up for that. He’s lost his job, his reputation, his access, perhaps his place in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science. But when it comes to reform, there’s only one type of accountability that matters: his honesty with himself. And he doesn’t seem to even be trying. He’s just looking for somewhere else to place the blame.