This is a story that is as old as humanity: Once upon a time, a woman was heavy with child. For nine moons, she was heavy, and at evening her time came to birth, and the labor pains came upon her. And the child was born, and lo, there was bleeding all the night. And she was nigh unto death.

This story could have taken place 3,000 years ago or last century, but it also could have been three weeks ago. It could have taken place far away, in the developing world, with little care; but also, rarely but sadly, in your suburban, high-tech, modern hospital.

Pregnancy and childbirth usually go well, but there is always risk. One of the largest risks for women, one of the leading causes of pregnancy-related mortality, has always been—and unfortunately still is—postpartum hemorrhage.

A few years ago, I delivered a beautiful baby at 3:06 a.m. after an uncomplicated labor. I put the baby on Mom’s chest, and everything went fine until 3:10 a.m., when the placenta delivered. Then, as sometimes happens, the uterus failed to contract. It was relaxed and floppy; it didn’t start to grow smaller as it should almost immediately after delivery. And as happens, the uterine bleeding started and wouldn’t stop. I tried medications and uterine massage. As less often happens, those did not work.

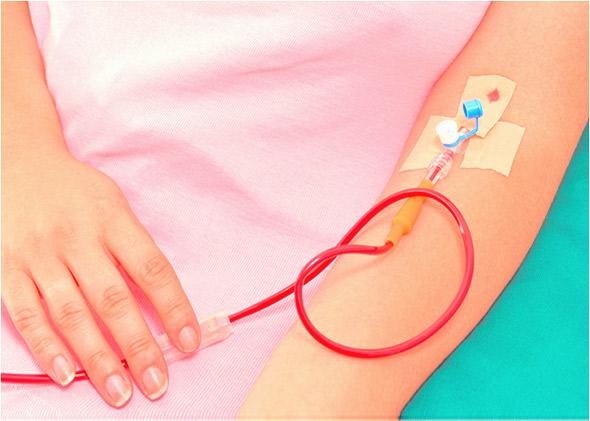

As our protocol states in such a situation, and as I’ve done many times before, I started transfusing the patient with blood when it was clear that our early interventions were not working quickly. While transfusing, I used various techniques and surgical equipment to slow the bleeding down. I used old ideas, such as manual compression of the uterus and a full examination to make sure that nothing else was causing the bleeding. I used new ideas, such as placing an intrauterine Bakri balloon for circumferential uterine compression, with bedside ultrasound to help position it properly. Nothing helped.

I called for anesthesia, and nursing help; when their help came, together we called for more help. We placed extra IVs. We tried more medications, more maneuvers. Nothing helped.

While working, I explained to the patient and her husband what was happening; I explained that we needed to go to the operating room. He was terrified; she was not able to talk to me much, which was itself terrifying.

We took the patient to the operating room. We put her to sleep. We opened her belly. We started to remove her uterus. Everything bled; places where we put stitches bled; places we touched with our cautery bled. Nothing stopped the bleeding. By 4:30 a.m. I had the terrible, nauseating, sinking feeling that I’ve only had a few times in my career: I was pretty sure this woman, this new mother, was going to die.

* * *

She didn’t die.

She didn’t die, but not because I’m such a smart doctor. It’s not because the anesthesia team was amazing, or because our excellent surgical backup team, the gynecologic oncologists, the premier surgeons of the female pelvis, were so rapidly available, although those things were true. She didn’t die primarily because we had a massive transfusion protocol.

What’s a massive transfusion protocol? I once joked to someone that it’s like an endless bento box lunch, except that we’re talking about something much less appetizing (and much more important): blood products. MTP essentially has two parts. Part 1 is that when the call goes out to my hospital blood bank activating the protocol, the blood bank sends me a cooler of blood products. Those products will be elegantly laid out; the box will have all of the red blood cells, clotting factors, and other things that my patient needs—the functional, preplanned, perfectly proportioned bento box. These lifesaving liquids will be arranged in a precalculated ratio—just the ones that the patient needs, just the ones that research has found to be most helpful in these situations—so that the surgeon does not have to stop to do math or look up how bad the patient’s labs have gotten.

And Part 2 of the MTP is the endless part: The coolers will keep coming—until the bleeding has stopped or the patient has died. They will keep coming until we can’t use them anymore.

The idea behind MTP came largely from trauma surgery, and most of that comes from a very different setting: soldiers and war. From those studies, modern medicine began to understand what was happening when people lost blood. Previously, medical thinking was that it was best to wait until the need for blood became demonstrable—until lab work or vital signs became markedly abnormal—and then start the transfusion. That was partly because the transfusion did not seem necessary yet, partly because blood products have always been a costly and limited resource, and partly because all blood transfusions run a risk of adverse reactions. But we’ve learned recently that by the time the body is showing the stress of blood loss, it is often too late. Because blood is an agent of clotting as well as oxygen delivery, by the time bleeding is dramatic, the body has entered a terrible spiral of poor clotting leading to more bleeding leading to instability and death.

So for the past decade or so, we have changed how we handle large-volume bleeding. We are no longer stingy: We give blood products earlier, and we give more of them; then we give more of them, and more of them. And sometimes the patient who would have died lives instead.

What is interesting to me about the MTP is exactly how non-technologic it is. It’s not robots, or lasers, or new pharmaceuticals. The only technology in play is blood transfusion, which is about 300 years old. All the MTP really is is a list, shared among the surgeon and the anesthesia team and the blood bank, and an agreement to do the things on that list. It’s committee work, really; dull and old-fashioned, and it’s the most powerful tool I’ve ever had the honor to wield.

It is because of that dull, old-fashioned committee work that one of oldest stories, on that terrible night, ended this way, instead, that morning: And lo, she came nigh unto death, but in the daylight, she was restored to life. And her family and her healers wept, and were thankful.