When best-selling true-crime writer Ann Rule died earlier this week, it was hard to miss the irony that, at the time of her death, she was embroiled in a true-crime drama of her very own. No, no one in her life was revealed to be a serial killer, like her former co-worker Ted Bundy, whom she wrote about in her first and best-known crime tale, The Stranger Beside Me. In fact, it wasn’t murder at all.

Instead, the criminal activity was a much more common and mundane sort. Earlier this year Seattle prosecutors had charged two of Rule’s sons with theft. The victim? Their ailing, elderly mother, whom they had bullied and tricked into giving them more than $100,000 over an 18-month period, prosecutors alleged.

News of Rule’s troubles came about a month after Alabama authorities declared that To Kill a Mockingbird author Harper Lee was not a victim of elder abuse, and able to consent to the controversial publication of Go Set a Watchman—this, after a lifetime of claiming she would not publish another word, ever.

The Alabama decision, to say the least, has not been universally applauded. Many remain convinced there is something not quite right with the story Lee’s lawyer, Tonja Carter, has told about finding the book’s manuscript —the New York Times, for instance, made the case that Go Set a Watchman was discovered not last year as claimed, but in 2011. Last week Marja Mills, a journalist who wrote a memoir about her friendship with Harper Lee—known as Nelle to her family and friends—and her late sister and lawyer Alice Lee, came forward in the Washington Post. “Poor Nelle Harper can’t see and can’t hear and will sign anything put before her by anyone in whom she has confidence,” she quotes Alice Lee as writing before her own death. Joe Nocera, also writing for the New York Times, flatly declared the episode “one of the epic money grabs in the modern history of American publishing.”

It’s likely we’ll never know where the truth lies. It’s also likely we’ll be hearing about these sorts of disputes much more in the future.

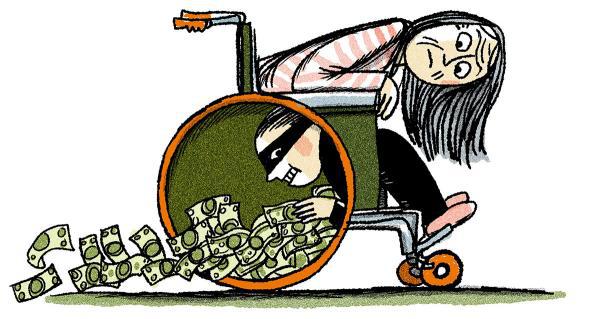

According to the experts, financial abuse of the elderly—or suspected financial abuse—is set to become a defining fraud of the next several decades. The motivation is basic: As Willie Sutton famously observed about the banks, the elderly are, increasingly, where the money is. Seniors have assets, and they often own their homes outright. Combine that with the estimate that people who make it past the age of 85 suffer about a 50 percent chance of suffering from a significant cognitive decline like Alzheimer’s, and you can see why the problem is so large.

Think of it this way: Monetary abuse of the elderly is, in some ways, the financial equivalent of date rape, often leaving victims shamed, embarrassed, and blaming themselves for their own victimization—and, as a result, unlikely to come forward. Others aren’t even aware anything is wrong, or that what happened to them was illegal. It’s also often committed by intimates, like paid or family caretakers or trusted advisers. Even when it’s a scammer, it’s someone—a contractor, or magazine salesperson—who has gained the victim’s trust. That, of course, only makes their situation worse.

It also leaves us in the dark about the true size of this particular financial-abuse problem. Experts have widely varying estimates—which is what happens when few report it. At the low end, the MetLife Mature Market Institute claimed in 2011 the elderly were taken for $2.9 billion annually, but the group’s director of research subsequently admitted he believed the group’s study had likely significantly underestimated the extent of the problem, since it relied on published reports to draw its conclusions. “What we’re seeing is the tip of the iceberg,” he told Consumer Reports two years later.

At the high end, True Link, a company specializing in protecting seniors from fraud and that, obviously, has a vested interest in making the problem seem huge, claims men and women over the age of 65 lose an astonishing $36.48 billion annually to everything and everyone from Nigerian emails to children and other caretakers. That study was based, in part, on online polling, which isn’t exactly known for its methodological soundness. The truth is almost certainly somewhere between these two numbers.

Certainly, these cases are not exactly hard to find—last week Deadline Hollywood highlighted the sad fate of Eunice Bellah, the widow of the late and acclaimed television and film art director Ross Bellah. A few years after her husband’s death, the longtime family accountant deposited Eunice Bellah in a nursing home, sold her residence, and listed possessions ranging from wheelchairs to artwork on Craigslist, with longtime family friends powerless to intervene.

And while a 2012 poll conducted by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards found more than half of those polled had elderly clients they suspected had been victimized by financial abuse, many financial advisers are also part of the problem. The free-lunch circuit—where seniors are treated to a meal at a place like Ruth’s Chris Steak House in return for listening to a financial pitch—is notorious, so much so that when AARP studied it in 2009, the group discovered almost half of those they surveyed who attended such a meal had the host ask for a private follow-up appointment at their personal residence, where they attempt to sell them on investments that may or may not be right for them.

It’s not like authorities aren’t attempting to put a stop to this sort of behavior. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is attempting to educate seniors and their caretakers about what they need to look out for when managing their funds. The Department of Labor’s push to expand the fiduciary standard—that is, the requirement that financial advisers act in their clients’ best interests at all times—to cover retirement savings will likely put a stop to a certain percentage of shady financial behavior, as well.

But, ultimately, human nature is human nature. It’s not like this is a new problem. Historians say that wills from the 18th and 19th centuries frequently contained language that said bequests were contingent on the recipient having taken care of the deceased in old age.

It’s the personal accusations that rip families and friends apart on a seemingly regular basis, after all. A few years ago, it was socialite Brooke Astor’s grandson who stepped forward to j’accuse his father of letting his grandmother spend her final days in squalor while he helped himself to her not-inconsiderable funds. In Rule’s case, two sisters and a brother pointed the finger at their other two siblings.

As for Lee, this is the second go-round. In 2013 she settled a suit with former agent Samuel Pinkus, one claiming he tricked her into signing over the copyright to To Kill a Mockingbird to his firm, Veritas Media, in 2007, and demanding a return of royalties.

Among the lawyers who helped Lee sort that mess out? One Tonja Carter.

All in all, a story Ann Rule would have loved.