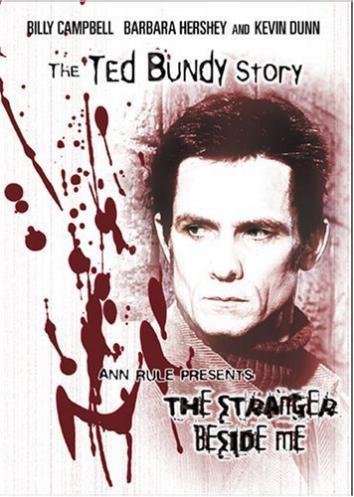

Icon of furtive ladyreading Ann Rule died on Sunday at the age of 83. If my Facebook feed is any indication, she will be remembered fondly by roughly every woman over the age of 15 who enjoys reading. True crime, the genre Rule ruled, has a remarkable shelf life for relatively timely journalistic endeavors—true-crime books are passed down among generations and snatched up in used-book stores. A glowing obituary in the New York Times touches on all the highlights—particularly The Stranger Beside Me, Rule’s 1980 smash about Ted Bundy, whom she befriended when they worked on the same suicide hotline before she discovered he was a serial killer. The obit also had one detail about Rule’s career I hadn’t known before:

She began writing for True Detective in 1969 under the pseudonyms Arthur Stone, Chris Hansen and Andy Stack, using male names at her editors’ insistence. She wrote two 10,000-word articles a week for the next 13 years.

That’s True Detective, the glorious tabloid rag of the 20th century, not True Detective, the dreary HBO show whose self-seriousness is tarnishing the True Detective name.

It’s interesting to consider, all these years later, that editors worried about readers not taking female writers of true crime seriously, especially since the genre is such a women’s genre. There aren’t hard numbers on this, alas, but if you see a shadowy cover image of a scary house interspersed with smiling yearbook photos of victims and a grisly title in a high-impact font, it is highly likely that a woman is behind that cover reading that book.

Why did ‘60s-era editors shy away from letting female-heavy audiences know that their fellow lady humans were writing the grisly stories they loved so much? Did they think the stories would have more impact if they were perceived as coming from an authoritative male voice? Was it about upholding the illusion that women are too delicate for such matters, even though editors must have known that women made up the bulk of the audience? The answers are lost to the mists of time.

Another mystery is why women are the dominant fans of true crime in the first place. There have been completely implausible “evo psych” explanations for it, with researchers speculating that women are searching the texts for tips on how to stay safe, even though men are actually more likely to be victims of violent crime. (Slate’s Jessica Grose once cast cold water on this theory, reminding us of the obvious: that people read true crime to be titillated, not to assess their own risk profile.) Maybe estrogen makes you more macabre.

Or maybe one clue can be found in an Ann Rule quotation from CNN’s obituary. In a 1999 CNN interview, Rule said she once feared that writing about murder all the time would leave her jaded, but it hadn’t. “I am not a cynic, because I find at least three dozen heroes for every bad guy or gal I have to write about,” she said. “The good in humanity always comes out way ahead.” Perhaps women, for whatever reason, are more keen on stories that take you to the darkest edges of humanity, but then reassure you that, amid the violence and horror of a few of us, most of us are good and decent people.