This article is an excerpt from the book Brazillionaires: Wealth, Power, Decadence, and Hope in an American Country, now available from Spiegel & Grau. It is the story of the rise of contemporary Brazil and our new era of global hyperwealth—told through the lens of that country’s glittering array of colorful billionaires.

For a few months after I moved to São Paulo, I lived a block from a freeway known as the Minhocão, which means Big Worm. People came up with the name because of the way it writhes for 2 miles through the city center, carving a path through exhaust-stained high-rises. Whole rows of windows are level with the traffic, close enough to spit on it, so residents keep shutters closed against the noise and the eyes of drivers. At 6 p.m., all four lanes are thick with lurching cars. Motoboys on their motorcycles cling to the fading paint lines, emitting brief honks that add up to an uninterrupted hum. Anywhere they can reach, in places it’s hard to figure out how they reach, kids paint the black runic-looking graffiti of pichação. There’s no neon, no billboards, because a few years back São Paulo banned most ads in public spaces. They called the law Cidade Limpa—”clean city.”

For a long time I just took the Big Worm for granted, another piece of São Paulo’s landscape of gray. As I learned the names behind the concrete, though, I came to see it as a symbol of something else: wealth. In Brazil, two of the oldest ways of getting rich are politics and public contracts. It’s an essential symbiosis, and to understand how some of Brazil’s richest families made their fortunes, you have to learn about the men who made government into a business opportunity. Progress never came unencumbered here: Mixed up in the quest for national development, you find an accumulation through exorbitant transfers of taxpayer money, outright theft, and even torture. It’s a contradiction at the heart of Brazil’s ambitions.

Paulo Maluf likes to take credit for the Big Worm. In a series of top government posts in São Paulo, Maluf oversaw the construction of hundreds of miles of tunnels and roads and overpasses. In his authorized biography—Him: Maluf, a Path of Daring—he declares, “No one can go a kilometer in São Paulo without running into one of my projects.” Some of his projects even helped speed up traffic—for a while.

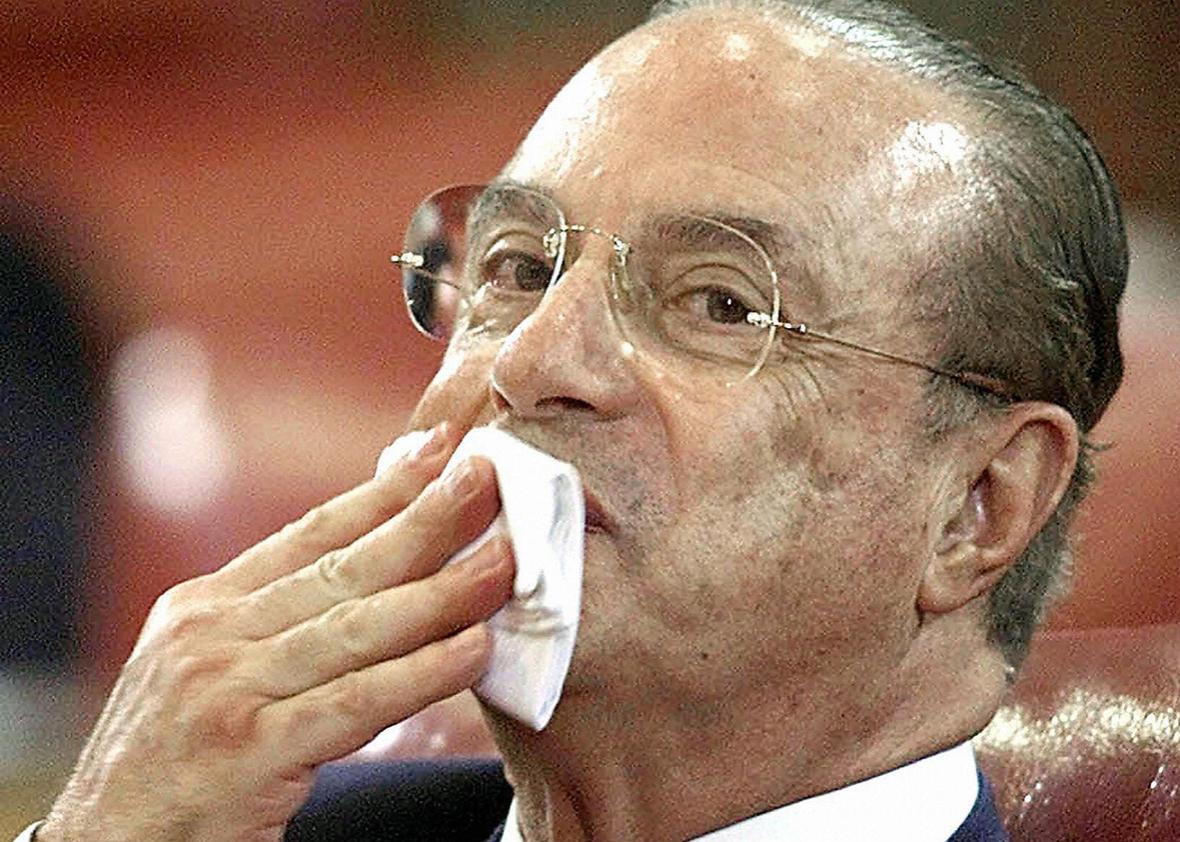

After half a century in government, Maluf has also been accused of spectacular feats of corruption. In agreeing to try a case against him in 2011, one of Brazil’s Supreme Court justices cited evidence that Maluf may have skimmed $1 billion from public works in just the four years he spent as mayor in the 1990s. Maluf is wanted by Interpol, the international police organization. For a while on Interpol’s website you could see a low-quality JPEG of his plump octogenarian face, with big rimless eyeglasses and a receding crown of slicked-back gray hair, his half-smile revealing a row of white teeth. He looks like a nice old uncle trying to hide his debauched side. He made it on Interpol’s list after the New York City district attorney indicted him on charges of laundering $11.7 million through the city’s banks. He’s got tendrils of cash snaking through bank accounts all over the world, allegedly.

Maluf has always denied it all. He denies ever even having owned an account abroad. And in Brazil, he’s a free man. Brazil doesn’t allow its citizens to be extradited, and in 2007, when he was elected to Congress, he won constitutional immunity from criminal prosecution by any court except the Supreme Court. At the time, he faced four different indictments for corruption, money laundering, conspiracy, and falsifying documents. Because the statute of limitations is halved when you turn 70, the court found Maluf too old to stand trial for the last two charges. Maluf’s lawyers argue he can’t be tried for money laundering because it became a crime in Brazil only in 1998, after the alleged crimes were allegedly committed. That’s their defense. But the Supreme Court justices agreed to try him—someday. It could take a while, considering their backlog: Dozens of other congressmen face corruption charges too.

Comedians love Maluf. In one bit, the presenters of a television comedy show called CQC meet him at his home in São Paulo, a 33,000-square-foot mansion half-obscured by sculpted trees, flawless hedgerows, and tall walls topped by electric wire. Maluf is passionate about cars—on weekends he’ll take a spin in his Porsche 996, the engine humming with horsepower jacked up to double the factory level—but he lets CQC take him around town in a minivan. He waits hidden inside as a comedian asks people on the street what they think of Brazilian politicians. “There’s a lot of malandragem,” one guy says. “They steal a ton, and they don’t care about the country.” What about Maluf specifically? “He’s bad.” And would the guy say this to Maluf’s face? “Definitely.” Then Maluf emerges from the minivan and approaches with outstretched arms and that goofy smile. The guy is freaking out, but he accepts the hug, and Maluf makes his pitch about all the roads he built. Of the allegations against him, Maluf asks, pointing his finger in the air, “Have you ever seen one bit of proof? One bit?”

“No one ever finds anything,” the guy concedes with a chagrined smile. He says this because most people don’t read court documents for fun. But one case from the British island of Jersey shows in detail how Maluf works: Brazilian prosecutors brought a civil suit in 2009 seeking to recover $10 million Maluf had stashed there. The suit centered on a road that gained fame as the most expensive in the world, mile for mile: Roberto Marinho Avenue. Completed in the ’90s, it spans 3 miles and cost $400 million. Maluf claimed it was simply a very high-quality road. But the project hid what I’d come to recognize as a typical Brazilian slush fund. The construction firms in charge, Mendes Júnior and OAS, presented inflated costs to the city government, a practice known as superfaturamento—charging an artificial markup on an order of cement, say, or billing for cement that was never even purchased. As mayor, Maluf signed off on the price increases. In the case of Mendes Júnior, the firm would transfer the extra money to a subcontractor, which kept 10 percent as its take and wrote checks for the rest. Once they’d cashed the checks, Mendes Júnior employees would hide stacks of hard currency in boxes of chocolate and cases of Johnnie Walker Red Label. An intermediary would then deliver the packages to Maluf or his deputies. Maluf’s typical cut was 20 percent, according to prosecutors.

Yasuyoshi Chiba/Getty Images

To move ill-gotten funds out of Brazil, you turn to a doleiro (the word comes from “dollar”). He’ll open an account for you abroad, usually in the name of a front man. You give the doleiro cash in Brazil, and undeclared dollars land in your new anonymous account. As part of a plea bargain, a doleiro who’d received cash from Mendes Júnior testified to having deposited the amounts in a secret Maluf account at New York’s Safra National Bank. With the help of authorities in New York, Brazilian investigators discovered that Maluf had used this account for personal expenses, once withdrawing $56,385 to buy two gold watches from Sotheby’s. But usually the funds didn’t sit there long before he transferred them to two accounts with Deutsche Bank across the ocean in Jersey. The authorities in Jersey found that the accounts were held by Maluf-controlled companies registered in the British Virgin Islands.

The press calls Maluf the Teflon man, since nothing ever sticks to him. This probably explains Maluf’s good humor about his fame for graft. After his name became a verb for misappropriating public funds—malufar—someone from CQC asked him how he felt about it. Without losing his cool Maluf replied, “This is all in your head. Malufar, in my mind, is to work, to build. … It’s been 46 years of arduous work.” There’s a saying in Brazil: “Rouba mas faz”—He steals, but he gets things done. In a poll from 2013, 12 percent of paulistanos called Maluf the best mayor the city ever had. He visibly got things done: all those roads.

* * *

That line from Balzac—”The secret of great fortunes without apparent cause is a crime forgotten, for it was properly done”—resonates in Brazil. But people tend to misremember it, omitting the words “without apparent cause” as if all wealth were tainted. There’s ample reason for this. Maluf got into politics by engaging in the ultimate form of campaign finance. As head of his family’s wood products business, he donated money to a think tank known as Ipês before the country’s coup of 1964. Ipês’ function was to unite business leaders and military officers in a conspiracy to take down João Goulart, the left-wing president, while designing a kind of shadow government that could step in afterward. It coordinated with the American ambassador and the CIA. Comparing the Forbes list with one of Ipês’ backers, I saw some of the most powerful families in Brazil today—Klabin, Gerdau, Ermírio de Moraes—on both. It dawned on me that many of Brazil’s great fortunes contained the traces of crimes committed in the name of keeping the economy free.

Many businessmen had expected the military to bow out after the coup, and grew disillusioned as the regime dug in and hardened. Many others, though, went further in their support. In July 1969, the generals created an anti-subversion unit in São Paulo known as Operação Bandeirante, Oban for short. The regime kept the operation off budget at first, so the officers in charge had to raise outside money to fund it. Bankers pledged payments of around $100,000. Some industrialists provided equipment on top of cash; Oban’s agents drove trucks lent by Ultragaz, a fuel distributor. Ultragaz’s president, a Danish expat named Henning Boilesen, even liked to watch the violent interrogations of subversives real and imagined. He’s said to have donated a device known as the Pianola Boilesen, an electric piano used to administer shocks to detainees. Maluf was serving his first stint as mayor by then, and when he raised funds for Oban, he gave it “the tone of a civic project,” in the words of one historian.

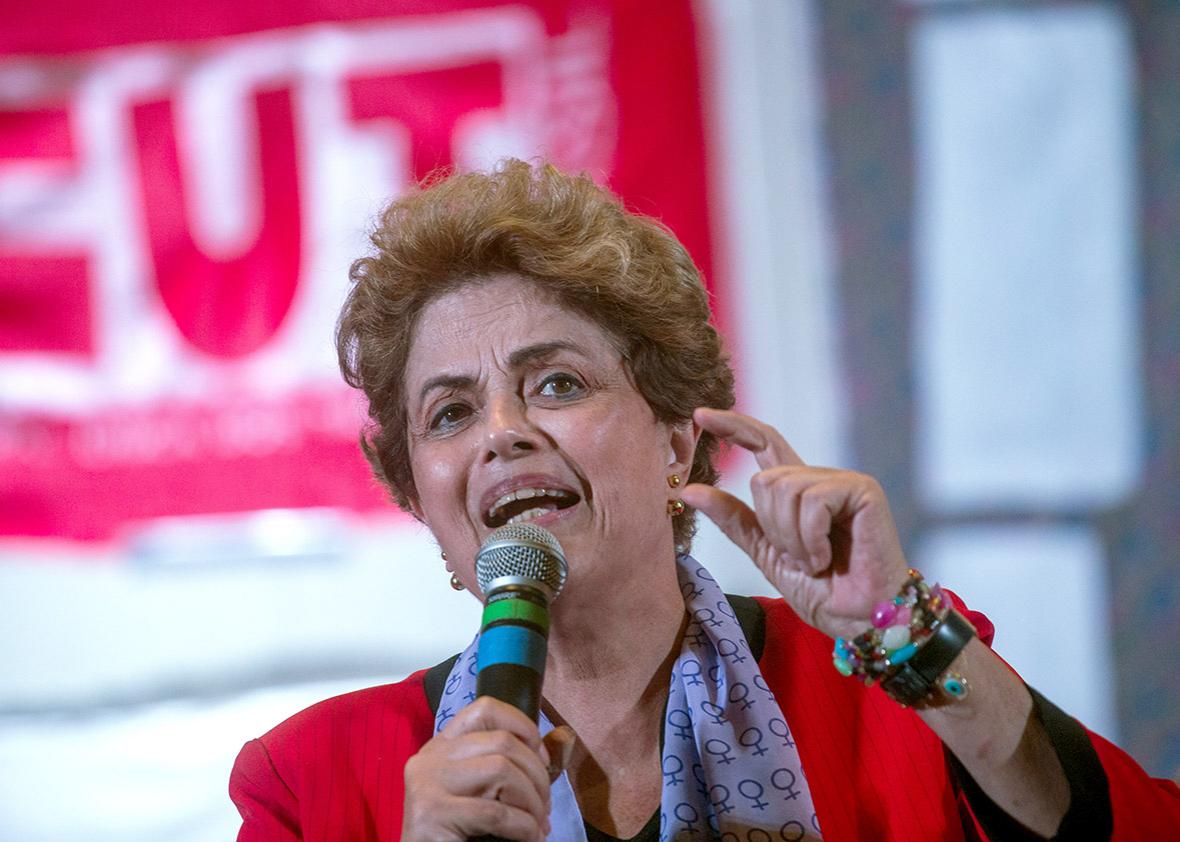

Four decades before she would become Brazil’s first woman president, Dilma Rousseff was forced to endure Oban’s interrogations. At 19 she had joined an underground guerrilla group, one of many that emerged as the regime cracked down on protests, student groups, any legal kind of opposition. When she was arrested in São Paulo in 1970, government agents took her to Oban’s headquarters in a middle-class neighborhood near Paulista Avenue. “The first time I had a hemorrhage was at Oban,” Rousseff would say many years later. “It was a uterine hemorrhage. They gave me an injection and said not to hit me that day.” There’s a photo of Dilma appearing before a military tribunal that year. Slim with close-cropped hair, she wears a look of cold determination while two military judges cover their faces in the background.

Ultragaz’s trucks still deliver cooking gas in cities across Brazil. To announce their arrival, they play a jolly Muzak xylophone tune overlaid with an eerie flute. Each time one rolled through my neighborhood, I couldn’t help but think of Boilesen’s device. By then, the family that founded Ultragaz was worth $2 billion.

* * *

One civilian in the military government later said that pretty much everyone in São Paulo’s business elite ponied up for Oban. Foreign companies, too. Still there were those who stood out. A truth commission launched during Rousseff’s presidency would name Sebastião Camargo, owner of the construction firm Camargo Corrêa, as one of Oban’s top sponsors. Through a joint venture with Ultragaz, he even provided frozen meals for Oban’s agents. His company would build one of São Paulo’s first stretches of subway while Maluf was mayor in the ’70s. Nearly half a century later, his family remains one of the wealthiest in Brazil.

Camargo spent so much time rich, it’s hard to think of him any other way, but he grew up poor. One of 10 children, he was born in 1909 to a couple of farmers in a small town in São Paulo state, of which São Paulo is the capital. When he was 6, he quit school to help support his family. He worked at a coffee warehouse and then as a laborer for a small construction firm, where he rose to overseer. He was still a young man when he started his own business, hauling sand for a road project with a small fleet of donkey-pulled carts. He wanted to expand, to win road projects as the main contractor, but wit and hard work could take him only so far. Luckily he met a lawyer named Sylvio Corrêa, who’d married the sister of an up-and-coming politician, Adhemar de Barros, and had money to invest. In 1939, they founded Camargo Corrêa. Adhemar had become the governor of São Paulo, and with him as their padrinho político—political godfather—the two partners won highway contracts around the state. It was for Adhemar that people came up with rouba mas faz, the expression later applied to Paulo Maluf.

Dio5050/Thinkstock

Sebastião Camargo was a talented businessman, but his success came in his ability to get along with whoever was in power. He worked well with President João Goulart, and then he grew tight with the generals who overthrew Goulart in 1964. Three years later, the military’s High College of War awarded him an honorary diploma. Camargo Corrêa used to keep a black-and-white photo of the event on its website: A little man with a mottled bald head, Sebastião stands smiling in an auditorium of besuited men. For his squinty eyes, he earned the nickname China.

He was a typical figure in the small business world of those years. He owned a mansion in the tree-canopied neighborhood of Jardins, not far from Maluf’s. He liked to be called doutor, a Latin American term of respect (which implies no medical training or formal education at all). He wore a gold tie clip and was almost always smoking a pipe filled with Dunhill 965 tobacco. He had extravagant tastes. At his office he had paintings of lions devouring zebras and elephants mired in mud, and he would show visitors photo albums from his big-game hunting trips to Africa and the Arctic. When he threw parties for his three daughters—sweet fifteens, then engagements—social columnists came to write about the movers and shakers in attendance. Officials from the military government always showed.

If Camargo stood out among Oban’s backers, as a public works man he also had more to gain. And indeed, his support came back to him in the form of public contracts assigned to Camargo Corrêa. It was a period of massive government investment in highways and bridges and dams, much of it financed with loans from the American government and the World Bank. One uncomfortable fact of the dictatorship is that its most brutal period of repression, os anos de chumbo—the years of lead—overlapped with what Milton Friedman called “an economic miracle.”

* * *

As an outsider, I had a hard time, at first, understanding the Brazilian version of entrepreneurship. Characters like Paulo Maluf and Sebastião Camargo didn’t fit the American ideal of the brilliant innovator who achieves greatness without any help from the government or powerful friends and family. But then I started dating a history Ph.D. student from the south of Brazil, and she recommended a great book from 1936: Roots of Brazil, by Sérgio Buarque de Holanda.

Buarque, a sociologist, wanted to explain Brazilians to themselves. He defined the archetypal Brazilian as “the cordial man.” In the word cordial, what mattered most for him was its Latin root: “of the heart.” In a society moved by the heart, you prize personal ties over impersonal institutions. It’s an attitude that goes back to Brazil’s earliest days, when the Portuguese crown awarded a few well-placed men “hereditary captaincies,” land grants that encompassed vast stretches of the country. The captains in turn doled out parcels for sugar plantations and cattle ranches. Unlike the freewheeling colonies of North America, power here worked strictly top-down. Bureaucracy was one of the few career paths for would-be, self-made men. One of the richest Brazilians of the 16th century built his fortune doling out favors as an assistant to the colony’s governor-general. Above all, government meant patronage, the power to distribute posts and favors to family and friends. Your ability to snuggle up to power mattered more than your business acumen. It was a meritocracy of schmooze.

There’s an old saying: “For my friends, anything. For my enemies, the law.” Brazil’s first real business elite got rich breaking the rules. It was made up of slave traffickers who greased palms to skirt Lisbon’s ban on international trade by native-born colonists. The slavers’ wealth was an open secret, but it got an official stamp of approval when João VI brought the Portuguese royal family to Rio in 1808. Strapped after his narrow escape from Napoleon’s forces in Europe, he offered them titles of nobility in return for cash. Even after the slave trade was banned under pressure from England, local authorities looked the other way when shipments of slaves pulled into port. This gave rise to the expression “para inglês ver”—for the English to see—still employed whenever the rules are broken and everyone kind of knows it but nobody says anything.

Brazilians never drew a clear line between public and private. This is one reason corruption in Brazil is so entrenched. Corruption is part of the culture, even the language here. So many people secretly hold assets in others’ names that there exist at least two slang terms for front man: testa de ferro (figurehead) and laranja (literally “orange,” an etymological mystery). Rabo preso (tied tail) refers to the gentlemen’s agreements that keep corrupt politicians from outing each other. (Imagine two rats with their tails entangled.) When a scandal dies smothered by the judicial bureaucracy, you say it ends in pizza (because of a famous dispute among managers of a soccer club, finally resolved over an order of 18 pizzas). Lots of words refer to tricks and cheats: trambique, negociata, mamata, maracutaia, falcatrua. Researchers estimate that between 50 and 90 percent of all political campaign spending is funded by caixa dois, the undeclared “second cash register” companies keep for bribes and under-the-table donations.

People talk a lot about the custo Brasil, the mysterious high price of everything here, but not as much about the lucro Brasil, the profits to be reaped from this system. According to one estimate, corruption shaves more than a percentage point from Brazil’s GDP. That’s around $20 billion. From a cold economic perspective, once corruption is the norm, you risk a competitive disadvantage if you fail to keep up. In the early ’90s, a journalist asked Emílio Odebrecht, son of the founder of the construction giant that carries his surname, whether his company had bribed a minister. He denied it but said he’d bribed other public officials, sure. In Brazil, he argued, you’re practically obliged to pay special favors to get things done. “I’m not going to say we’re an innocent company,” he said. “No company can survive if it’s innocent.”

Emílio’s statement helped me understand that Brazil’s bureaucracy has a purpose. It favors those willing to bribe their way through, creating a kind of cartel of lax ethics. Later, in an investigation known as Lava-Jato (Carwash), police would at last identify a formal cartel—in which Camargo, Odebrecht, and a few other top firms allegedly divvied up all the major contracts from Petrobras, the state oil company. It’s because of Carwash that Brazil has lately plunged into political chaos. The investigation has tainted just about every major politician in the country—including the president.

* * *

I understood why the Camargo family got along with whoever was in power. It was good for business. I had a harder time understanding what was in it for Dilma Rousseff and her predecessor and political mentor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—the legendary Lula. Both had resisted the dictatorship: Lula as a unionist, Rousseff as a guerrilla. Both had dabbled with socialism. Lula used to advocate defaulting on Brazil’s debt, nationalizing the banks, and redistributing land. But he lost three presidential elections this way, so he moved to the center. His running mate in 2002 was a textile magnate. He promised to respect Brazil’s financial obligations at home and abroad. He once called himself a “walking metamorphosis.”

Victor Moriyama/Getty Images

The markets tanked at first when Lula surged in the polls, but businessmen came around in the end. After he’d won the election, they gladly helped pay off his campaign debts. The biggest donations, as usual, came from companies that depended on the state for their income. Soon, a quarter to half of all donations to the Workers Party would come from the construction industry. In Lula’s 2006 campaign for re-election, Camargo Corrêa alone accounted for 4 percent of the total. (And that’s only what was declared.) Like old Sebastião, though, today’s construction giants didn’t play favorites. They gave to the opposition, too.

With his unionist past, Lula might look like an idealist, but even back in the ’70s he was willing to bargain with factory owners in hopes of striking a deal. Above all, he’s a pragmatist. He set aside the old Workers Party plank calling for an end to corporate campaign donations because elections are expensive. He welcomed old allies of the regime to join his coalition in Congress because he wanted to get things done. They were after patronage, so for them ideology came second, if at all. Lula used to promise to break with the corrupt old elite; instead, he worked with it.

My girlfriend, the Ph.D. student, had been a Workers Party stalwart for as long as she could remember. Her parents were middle-class lefties who’d supported the party since Lula had helped to found it in 1980. She told me the party had no choice but to grease the gears if they wanted to get their agenda through and lift up the poor with initiatives like Bolsa Família, a welfare program that now keeps some 50 million Brazilians from going hungry. In her view, skimming money from public coffers to spread around Congress was the Faustian bargain that made Brazil a more equitable country. Buying votes was nothing new in Brazilian politics, she said, accurately.

Rousseff continued Lula’s line. As president, she claimed to govern for the poor but put the same amount of money into Bolsa Família as into what some called bolsa empresário—the subsidy in state loans for businessmen. She didn’t disturb the truce with the old elite. She ignored the old Workers Party call for a tax on large fortunes. She became a pragmatist, too. One afternoon in 2012, at the presidential palace in Brasília, she’d just announced a plan to lend money to small farmers when Paulo Maluf approached her among a huddle of people. He took her hand, leaned over, and kissed it.*

Maluf may be corruption’s poster boy. He may have raised funds for Oban, where Dilma Rousseff was tortured. But he commanded a lot of votes, and the Workers Party wanted his support for São Paulo’s mayoral election that year.

Dilma looked matronly in her burgundy power suit. Her face had filled out since the lean years she spent in secret prisons. As Maluf’s lips left her knuckles, she smiled graciously at him.

Four years later, Maluf would vote to impeach her.* He’s still a free man.

This article was excerpted from Brazillionaires: Wealth, Power, Decadence, and Hope in an American Country by Alex Cuadros. Copyright 2016 by Alex Cuadros. Published by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All Rights Reserved.