Hi, Carl, Ann, and Lindsay,

It’s a pleasure to return to the Music Club! One of the reasons we participate in these end-of-the-year critical wrap-ups is to reflect on the way pop music helps us mark the passage of time. But life leaves those marks as well. This year I suffered two losses: my father and my older half brother, both within a matter of months. I’ve never thought so intimately about the limits of the human body and about the disposability of life as that moment when I carried home my father’s ashes from the crematorium in a tiny rectangular urn.

It’s also been hard this year to avoid thinking about that disposability on a much larger scale. Watching the 24-hour news cycle in America might have made you feel like the world’s gone berserk: We’ve been bombarded with stories about police killing unarmed young black men and women (and children) in the streets, school shootings, sexual violence, downed commercial airliners, and kidnapped girls in northern Nigeria—not to mention unrest and brutal atrocities in locales as far-flung as Palestine, Ukraine, Thailand, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

Even beyond social and political conflict, part of the reason modern life feels so discombobulating is because time seems to be moving bracingly fast and achingly slow at the same time. As you noted, Lindsay, we live in a culture that prizes instantaneity, as zip files and text messages careen across space-time in a flash; as Netflix allows you to batch-view an entire season of House of Cards in a single sitting; as Spotify and YouTube promise us the opportunity to retrieve audio and visual materials from any historical era with just a mouse click; and as photogenic Alex, a teenage staffer from Target, becomes a viral celebrity literally overnight. And yet modern life is also defined by the longue durée—some things just seem to take forever. Our warped sense of space-time was a major preoccupation in some of 2014’s most fascinating films: I’m thinking about Interstellar’s hard-science visualizations of black holes, wormholes, tesseracts, and alternate dimensions; and Boyhood, in which director Richard Linklater pulled a Michael Apted and shot scenes with his cast every year for 11 years.

I’ve written before that in pop music, D’Angelo’s entire career is a meta-commentary on time itself. You can feel his offbeat sense of time in those Dilla-inspired, lurching rhythms—but also in the fact that in 20 years he’s only ever released two studio albums, and the most recent, Voodoo, came out 14 years ago. (In contrast, D’Angelo’s idol Prince put out two albums this year alone.) After years of leaked tracks and squandered release dates, RCA borrowed Beyoncé’s astute December gift-dump strategy and rushed out Black Messiah over the weekend with no PR buildup or drawn-out marketing campaign. Kinda ironic—and quite cunning—to rush-release an album that was a decade and a half in the making.

It’s hard to discuss the artistry of Black Messiah outside of the savior-complex hype that’s surrounded its event-release, which is in turn inseparable from that doozy of an album title. But what I love about the record are its textured rhythm tracks, played by extraordinary musicians jamming in-the-pocket, calling forth sounds and sonics from Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain, and Al Green’s The Belle Album. I love those blurry, shuteye D’Angelo vocals. I love his tricky, psychodramatic lyrics (aided by Kendra Foster). And kudos to Russ Elevado’s hyperintelligent, vintage mix. Sure, we all know that D’Angelo has been coping with intense personal issues for the last 14 years—but I love the fact that Black Messiah stylistically continues from Voodoo as if he went into hibernation for the last 10 years and, upon waking up, jumped right back on to “the one” without missing a beat.

You could cynically describe 2014’s Black Messiah as retro-nostalgia for 2000’s Voodoo’s retro-nostalgia for ’70s and ’80s Prince, Sly, Stevie, Al, Isleys, Hendrix, and P-Funk. But I love how the album deploys the musical past to be perfectly on time in the politically charged present. Like a companion to Ava DuVernay’s ultra-topical Selma, Black Messiah captures the contentious zeitgeist moment that has Americans of all stripes taking to the streets to protest police brutality. It’s the 2014 musical answer to James Baldwin’s query in The Fire Next Time, in which he asks, “How can the American Negro past be used?” Black music especially matters at a time when black lives haven’t seemed to matter, and it matters at a time in which appropriated black style is all the rage (Iggy, Macklemore, Miley, etc.) even as black musicians themselves have been troublingly marginalized from the charts and from top awards. I’m also reminded of Stevie Wonder’s well-attended multi-city Songs in the Key of Life tour, in which the 64-year-old performed his classic 1976 double album (mostly) in sequence: It was like time-traveling back to that moment when albums themselves mattered. How many albums from 2014 will ascend to that classic status and fill large-scale arenas in 2052?

I’ve previously described D’Angelo as a chronic undersharer. At a post-shame cultural moment marked by social media oversharing, 2014 became the year that mystery in pop became viable once again. Up-and-comers like producer-artists Arca and Jungle concealed their faces and shied away from excessive PR in the effort to go Garbo on us; and even the notoriously reclusive Kate Bush, who hadn’t played live in 35 years, was surprised that her comeback to performing large-scale concert venues in London sold out for weeks on end in just minutes.

In contrast, extrovert Azealia Banks found a pot of gold at the end of the oversharing rainbow. After her breakout 2011 smash “212,” she went into multiyear self-sabotage mode, waging petty wars on social media as the public waited, and waited, for a full-length to arrive (though she continued to pull in six figures a year on tour). Broke With Expensive Taste, her 2014 debut, gave the haters lockjaw, and I’d vote for it as the hip-hop album of the year. I’m ever awed by Banks’ creative lyricism, her highly musical, polydimensional flow (the most adroit female MC-crooner since Lauryn or Missy, methinks), and her eclectically curated choice of left-curve, glitchy beats. How long does it take to create a great album in the second decade of the pressure-cooker, instant-centric 21st century? As long as it takes.

You can’t talk about the changing ways we experience time without talking about the changing way we’re experiencing space, too: This year’s catastrophic news of the Ebola epidemic ravaging several West African countries threw the media into high panic, especially as the disease traveled for the first time outside of the African continent. It served as a potent reminder that we’re all indelibly interconnected in an increasingly globalized world. (It also confirmed that M.I.A.’s 2007 Kala, thematically preoccupied with the circulation of disease and financial capital, was way ahead of its time.)

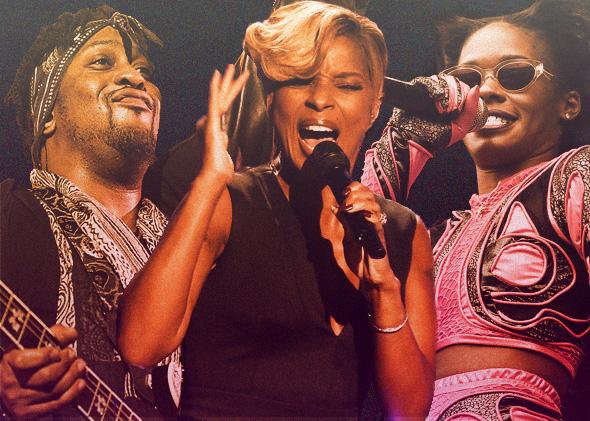

You saw that interconnectedness unfold across both sides of the Atlantic: British producers like Duke Dumont and Disclosure revel in the thump-thump of ’90s American underground deep house. Some might be initially disconcerted that the U.K. production teams concocting this exquisite soul-infused electronica seem to be predominantly white male duos under the age of 25, but if you do even a little bit of your homework, you’ll see it’s really a multicultural scene: They collaborate with vocalists and songwriters like Nigerian-British retro-vocalist MNEK and Sierra Leonean singer-songwriter A*M*E. Also, the fact that acts like Clean Bandit and Jungle are organized as loose-knit collectives means that they offer a stylistic alternative to auteurist British singer-songwriter hegemony (Ed Sheeran, Adele, etc.). While Britain has been looking back in space-time to American house and soul, Americans have also been looking across the horizon for cultural inspiration. Ann’s already written about Sam Smith’s impact on this side of the pond, and we all know that Mary J. Blige traveled to London to collaborate with Smith and other A-listers to develop her strongest album in years, The London Sessions. To paraphrase what I recently said for NPR, the album forces us to travel back in time to imagine an alternative 1990s in which Mary J. Blige gets signed to Strictly Rhythm and makes underground house music in London. Call the film version: Mary J. Blige: Days of Future Past.

Beyond just Britain, I think we could do more to talk about the global circulation of music, especially music outside the West. World music was a somewhat nifty marketing invention of the ’80s that might have helped bring global attention to the otherwise-buried work of non-Western musicians. But by 2014, it has no relation to how commodities like MP3s actually circulate in transnational culture and it only really serves to ghettoize non-Anglophone artists who deserve more critical and commercial attention. Moroccan Gnawa musician Hassan Hakmoun, an NYC transplant, rocked out this year on his little-heard Unity album. French-Cuban twin sister act Ibeyi (Naomi and Lisa-Kainde Diaz) released the minimalist electro-spiritual EP Oya on the famed XL label. Brazilian MC Karol Conká’s Batuk Freak was actually a 2013 release but didn’t get stateside attention until this year; it’s a visceral fusion of dance sounds that any Major Lazer groupie will love. Seun Kuti, the youngest son of the Afrobeat icon, outdid himself this year with A Long Way to the Beginning, an aggressive agitprop statement co-produced by Robert Glasper. Scottish rap trio Young Fathers (which includes Liberian-born Alloysious Massaquoi and Nigerian-British Kayus Bankole) took home the Mercury Prize this year for Dead: I’m pretty sure it’s the only rap album you’ll hear this year with synth bagpipes. On the charts, Afro-Norweigan duo Nico & Vinz had a global hit this year with “Am I Wrong.” Place them in a long genealogy of black European artists ranging from Shirley Bassey to Boney M to Neneh Cherry to Taio Cruz.

Chris, your chart breakdowns are always incredibly informative. I agree that songs that have populated the U.S. charts this year (as in previous years) are much more stylistically diverse than they’re often given credit for being. I tend to see the charts as an institution, in the same way that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is an institution, in the same way that the Grammys are an institution, as are record labels, and as is the police force. And as American institutions, they sometimes tend to reflect the exclusionary values we actually have rather than the inclusionary values we want them to have.

As we watch or participate in #blacklivesmatter protests in 2014 and as we see the court of public opinion come down hard on Bill Cosby (and Sony executive Amy Pascal), I think what we’re seeing is the beginning of a sort of crowd-flexing movement: The rise of public demand for mass action to make our institutions (and our citizens) better reflects the democratic values and ideals this country aspires to but has yet to achieve. To extrapolate, I don’t think it’s tenable to have an institution like the Grammys marginalizing artists of color at the same time that you have people in the streets protesting brutality and injustice and striving to simply participate on equal footing in all aspects of American democracy. How would the SoundCloud Awards, if they existed, look different from the Grammys?

It’s telling that Frozen and its blockbuster soundtrack’s pop feminism come to us at a time when even one-percenter women like former New York Times editor Jill Abramson, allegedly sacked for inquiring about the gender disparity in her pay at the newspaper, can’t seem to catch a break. To riff on Pharrell for a second, rooms may not have roofs, but they do have ceilings. That, of course, didn’t stop lots of women this year from letting loose. I could go on and on: Sia, Jennifer Hudson, Kierra Sheard (the best singer of her generation in any genre), Katy B, Jessie Ware, Kelis, Lady Gaga transforming herself into a new-millennium Liza Minnelli … I agree with everyone’s assessment about the brilliance of St. Vincent, though my favorite pop music visionary of the moment is Kimbra, who this year released The Golden Echo.

And Ann, while I co-sign your point that we need to see more women as producers, at this point I think we should also be questioning how many women are given the opportunity to be CEOs and owners of record labels. It would be great if someone would riff a bit more about the business and distribution aspects of pop, because I don’t think anyone who makes or consumes popular music in 2014 can afford to not have an ethical perspective on how we access music in an era of streaming services. Taylor Swift’s powerful decision to pull her music from Spotify was a mic-dropper. If the highest earner in music doesn’t want her music on the top streaming service, and streaming services are being pushed to us as the future of music, what do we do about pop music’s ever-shrinking middle class and its permanent underclass?

All of these identity issues in popular music come back to the issue of the limitations of our bodies. To quote Pharrell again, we might feel like a hot air balloon that could go to space, but we’re weighed down to Earth by the grave reality of phenotypes and chromosomes: In some ways, we’re still trapped and confined, or liberated and privileged, because of how we look and who we are in space and time. Michael Brown in part lost his life because police officer Darren Wilson thought he looked “like a demon”; Shoshana Roberts of the problematic Hollaback anti-street harassment video only had to walk down the street, as so many women do, to become victimized by men. In a year in which pop music was not only defined by issues of time but by a continuation of body issues—I’m thinking of Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda,” Meghan Trainor’s “All About the Bass,” Arca’s Xen, you name it—we’d do well to remember James Baldwin’s truism that everyone is “carrying one’s history on one’s brow, whether one likes it or not.”

Just as long as there is time, I will never leave your side,

Jason