“Knowing is good, but knowing everything is better.” That’s the credo of Eamon Bailey, the Silicon Valley luminary at the heart of The Circle, which adopts Dave Eggers’ novel into a flaccid cautionary tale about the dangers of technology. Eamon isn’t The Circle’s protagonist—that would be Mae (Emma Watson), a guileless “guppy” who gets a job at Eamon’s titular social media giant and quickly subscribes to its all-encompassing ethos. But he’s its most important figure, the one whose vision of the future has to be so seductively compelling that thousands would follow his every word, and hundreds of millions would make themselves part of his world.

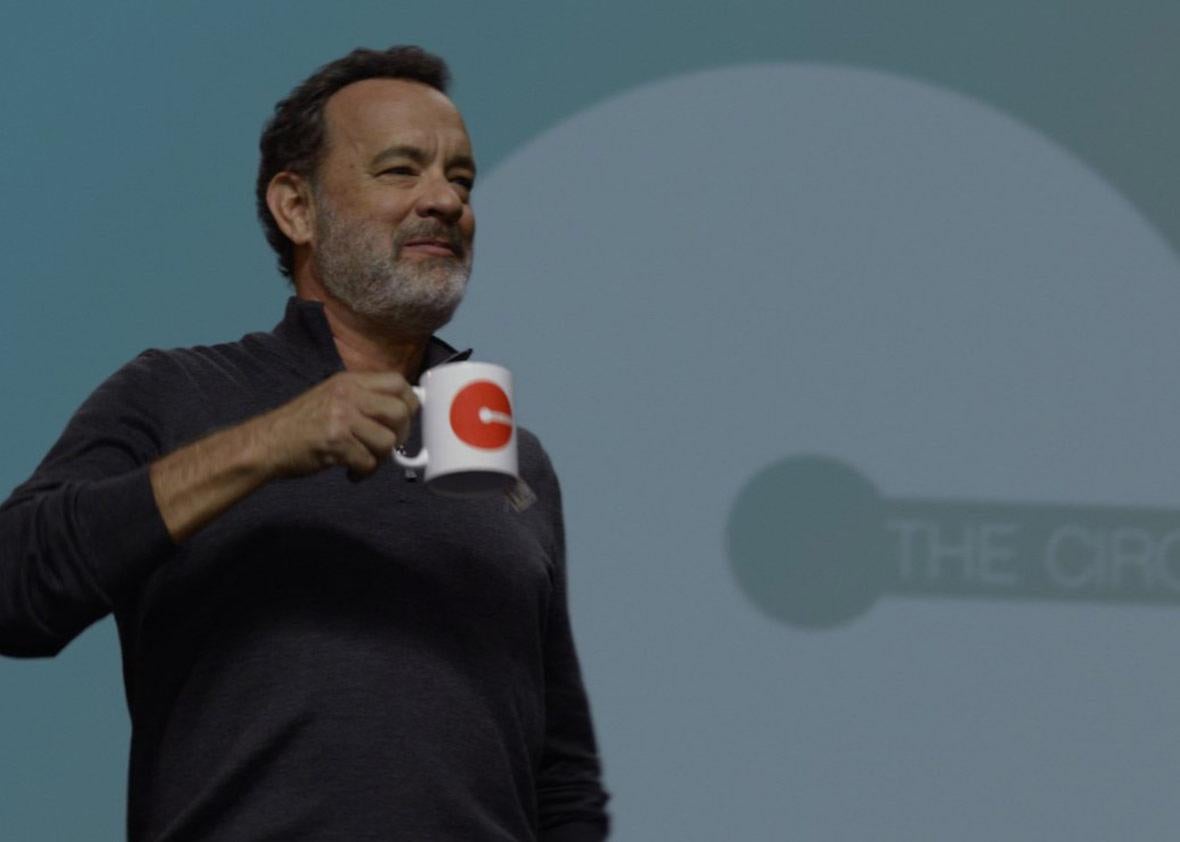

Given that Eamon is played by Tom Hanks, this ought to be a simple matter. Although he may no longer be the world’s biggest movie star, Hanks remains an almost universally beloved figure, one of the few faves who has never become problematic. In the past several years, Hanks has done the best work of his career excavating his role as “America’s Dad” from the inside out. In Sully, and Bridge of Spies, and Captain Phillips, he’s a man who rises to the occasion and is nearly crushed by it; the scene at the end of Captain Phillips when he realizes he can stop being a hero and let the trauma of his near-death experience take over his body is one of the most extraordinary moments in recent movies. But in The Circle, Hanks doesn’t seem to know whether he’s playing a deluded futurist who fails to understand the dangers of what he’s created or a snake-oil salesman who knows just what he’s doing—and the failure to distinguish between the two, or even to acknowledge how one can become the other, is a major part of what makes the movie such a damp rag. It’s like Black Mirror and Silicon Valley had a baby, and then left it to be raised by wolves.

When Mae first arrives at the Circle—a sprawling internet powerhouse whose core seems to be a Facebook-like service called TruYou—she’s overwhelmed by its expansiveness. A co-worker walks her through the basics of her “customer experience” position with the cheery briskness of a tech-support person with a dozen other calls in his queue, and she’s quickly hooked up to the site’s internal metrics, where every interaction is ranked and categorized, and even the slightest deviation from a perfect score can set off a panic. Mae—who confesses in her job interview that her biggest fear is “unrealized potential”—quickly gets up to speed, but no sooner has she mastered the basics than two concerned Circlers confront her with her failure to integrate into the company’s social networks. How does someone on the other side of the campus know what’s going on with Mae if she doesn’t post how her morning is going? She might consider, say, her dad’s multiple sclerosis a private matter, but the company has four related chat groups, two alone for the children of parents with MS. She doesn’t have to take part, of course, but like everything else, her participation or lack thereof will be noted and ranked, just as the Circle’s servers will note whether or not she takes part in any of the hundreds of fun-filled weekend activities that make going home to her parents even less enticing. Like so much 21st-century labor, the effort Mae spends establishing a digital footprint isn’t officially work, but it isn’t really optional.

As Mae gets deeper into the Circle, closer to the “Gang of 40” where key strategic decisions are made, it becomes clear that the company’s already immodest reach is only the beginning. In the name of transparency and openness, Eamon and co. want to bring everything from medical records to voter registration under their umbrella. It’s a sinister conspiracy with a smile, one in which people are taught to police themselves, to sic digital mobs on unbelievers like Mae’s childhood friend, played by Boyhood’s Ellar Coltrane, who just wants to live off the grid and make chandeliers out of deer antlers. (Don’t we all?) The story at the core of The Circle is Mae’s journey from skeptic to evangelist: how she learned to stop worrying and love the cloud. But Eggers and his co-adapter James Ponsoldt, who also directed, seem intent on making sure we know they’re immune to the siren song of big data. The Circle is structured like a Web 2.0 version of The Parallax View, where people enthusiastically consent to being perpetually watched, because it makes them feel less alone. Instead of employing that paranoid thriller’s vertiginous angles and imposing long shots, Ponsoldt frames his world in swooping, sunlit crane shots and quiet close-ups, sometimes annotated by the superimposed comments of those who are watching along at home.

Ponsoldt—who also directed The Spectacular Now and The End of the Tour—has a great feel for intimate conversation, but he’s all thumbs when it comes to The Circle’s attempt at stylized allegory. The movie’s characterizations are broad and bland, and the haphazard editing leaves apparently major figures stranded for long stretches of the story: Star Wars’ John Boyega turns up in what would seem to be a key role—and is then reduced to a mute, disapproving presence at the back of the room during the Circle’s in-house pep rallies. It’s a movie that thinks it’s bitterly ironic to have Mae’s cellphone ring with the Shaker hymn “Simple Gifts,” making Mae the only millennial in the U.S. with a MIDI ringtone. (It also features numerous scenes of symbolic kayaking.) For all its dire warnings about the dangers of the internet, The Circle feels less an urgent cautionary tale than a dyspeptic toldja-so, as if its primary purpose were to ensure that the people who made it could pull the film out in 10 years and say, “See?”