The tech world runs on chutzpah. Innovation and creativity are nothing without it. Steve Jobs drank chutzpah smoothies each morning and gargled chutzpah at bedtime. Larry Page and Sergey Brin embark on moon shots like the rest of us embark on our morning commute. Marissa Mayer drops $1.1 billion on a near-bankrupt blogging platform like it’s a modest payday splurge. And it’s partly thanks to Mark Zuckerberg’s youthful disregard for the right to privacy that Facebook exists at all.

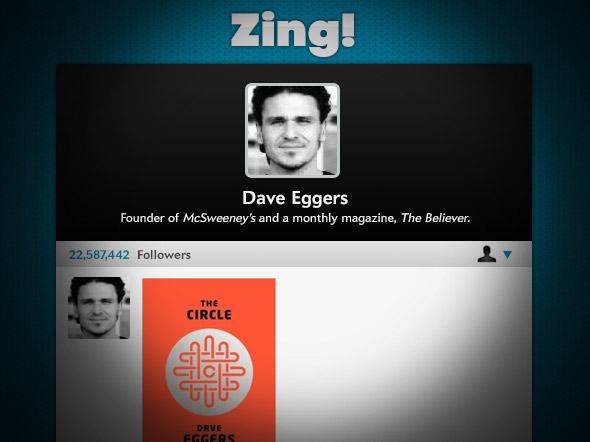

But all of these industry titans could learn a thing or two about chutzpah from Dave Eggers, because with The Circle, Eggers has written a nearly 500-page satire of the tech world while appearing to have little interest in the actual tech world.

This is not a criticism. This is a reflection of Eggers’ own statements, like the one he provided to Gawker’s Nitasha Tiku on Wednesday. In the process of dreaming up The Circle—named for the unimaginably colossal and powerful tech company, like Facebook smashed into Google, that employs most of his novel’s characters—Eggers says that he did not “read any books about any Internet companies, or about the experiences of anyone working at any of these companies … I avoided all such books, and did not even visit any tech campuses.” That’s a curious admission to make, admirable in its way, and helps to explain why The Circle sometimes reads like a satire of NASCAR in which all the cars are played by freight trains.

Yet the book is heavily, self-consciously egged with parallel-world verisimilitude: the ways the titular corporation’s three “wise men” evoke Google’s top executive trinity, the fact that the Circle’s founder is Mark Zuckerberg’s long-lost twin, the strong surface affinities that the Circle’s campus and culture share with Facebook’s and Google’s. Eggers denies having read Katherine Losse’s 2012 memoir of her time at Facebook, The Boy Kings, despite the many similar contours between his book and hers: Young woman takes a job at a social-networking company answering user questions, rises through the ranks, is at times put on public display without her clear consent, grapples with hard questions about privacy and information-sharing, and ultimately finds the company’s “cause” has swallowed her life and redefined her sense of self and other. One big difference: At the end of The Boy Kings, Losse leaves Facebook. There is no escaping the Circle.

The company’s foundation stone is the Unified Operating System, also known as TruYou, invented by Circle founder Ty Gospodinov, a hoodie-wearing “boy-wonder visionary” whom we first glimpse “staring leftward … tuned into some distant frequency,” an image grafted from Gospodinov’s 2010 Person of the Year profile in Time. The Unified Operating System, Eggers writes,

combined everything online that had heretofore been separate and sloppy—users’ social media profiles, their payment systems, their various passwords, their email accounts, user names, preferences, every last tool and manifestation of their interests … one account, one identity, one password, one payment system, per person. There were no more passwords, no multiple identities … You had to use your real name, and this was tied to your credit cards, your bank, and thus paying for anything was simple. One button for the rest of your life online.

So does this mean that despite operating system being two-thirds of its name, the Unified Operating System is not an operating system, like iOS or Android? Is it more like Microsoft Passport, Google Checkout, Google+, or Facebook Platform, plus self-tracking gadgets and surveillance cameras? The reader is told that “TruYou changed the internet, in toto, within a year,” that “the TruYou wave was tidal and crushed all meaningful opposition,” that it was “the force that subsumed Facebook, Twitter, Google”—and Eggers raises the stakes considerably in invoking that threesome, signaling to the reader that his satire is rooted in reality. (Steve Jobs is name-checked, too.) But how did TruYou subsume Facebook and Google, and so quickly?

The answer, Eggers implies—and here’s the seed of his plot and his critique—is that TruYou demands actual names, total transparency. It turns out that the free-market solution to monopolizing the Internet is simply to make people use their real names for all online activity. Notably, Facebook tried something akin to TruYou in 2007 with Facebook Beacon, which, in the words of the New York Times, took “a far more transparent and personal approach” to online tracking. It was a fiasco, resulting in complaints, a class-action suit, and the shutdown of Beacon in 2009. TruYou, somehow, is the opposite of a fiasco. Users love the streamlined experience and precision-targeted marketing. Plus, “overnight, all comment boards became civil, all posters held accountable,” Eggers writes. “The trolls, who had more or less taken over the Internet, were driven back into the darkness.” Back, stupid trolls! Advertisers are thrilled, too, because “the actual buying habits of actual people were now eminently mappable and measurable,” and by “now” Eggers presumably means “again, in a different way,” since the actual buying habits of actual people are eminently mappable and measurable via Apple ID for Advertisers, Google’s in-progress AdID, and other means.

This might all sound nitpicky. But when you’re reading a novel about the Internet by a writer who doesn’t seem clear on what an operating system is or who thinks that a unified ID-and-payment system could extinguish all trolls, everything starts looking like a nit to pick. Does the Circle have its own OS? Its own browsers? How much hardware does it make? If it’s constantly backing up every conceivable shred of its users’ data—if that’s its fundamental mission—where are its data centers? Why would the world’s other corporations agree to having the Circle’s cameras planted everywhere? Or have they been magically subsumed, too? And so on.

Because it is a fast-moving conspiracy potboiler, The Circle is far more entertaining than, and not nearly as maddening as, say, Jonathan Franzen’s apocalyptic rants about “the infernal machine of technoconsumerism,” even though Eggers seems just as appalled by the liking-and-sharing economy. From its opening lines—“My God, Mae thought. It’s heaven”—The Circle sends out a familiar distress signal about a cultlike movement, a Silicon Valley revival meeting, a utopia breeding a totalitarian nightmare. Mae, the protagonist, takes an entry-level position in “Customer Experience” at the sprawling, city-on-a-hill campus of the Circle, which is busy leveraging its stranglehold on the search and ad-serving markets and its deep reach into the psyches and pockets of the global populace to manufacture a total-surveillance society. Cameras for everyone, everywhere! Not 70 pages in, Mae attends an all-hands meeting starring Eamon, one of the Circle’s “wise men,” who delivers the Circle’s Nineteen Eighty-Four–style mission statement: “ALL THAT HAPPENS MUST BE KNOWN.”

Mae is pliant and credulous; her overweening gratitude for winning a job at the Circle readily twists itself into aggressive subservience to the corporation’s whims. She is the Circle’s experiment and exemplar, Facebook-Google’s ideal user-captive. With every day within the Circle, her attention is further divided among more and more screens, networks, and rankings. She must race to keep up with a never-ending stream of user questions, monitor the scores users give her (and grade-grub to improve them), participate in multiple social networks (Zing is basically Twitter, and “zing” is a verb) and a litany of work-related social events, and obsess over her “Participation Rank,” a kind of intracompany Klout score. Soon she is wearing a camera and mic at all times to broadcast her every action and the actions of every person she encounters, save sex and sleep and bathroom breaks—and maybe even some of those—to thousands or millions of followers.

Yet Mae is bizarrely naïve. A major plot point turns on her not knowing what one of the wise men looks like (even though he was Person of the Year!), and when she gives a presentation that receives 368 “frowns” (which are kind of like Reddit downvotes), it has to be explained to her that she can find out who frowned at her—that in fact, tracking what people like and dislike is what her company does.

Like Mae, we offer ourselves up for consumption and quantification by the minute, without bothering to understand what exactly is done with our offerings. But there’s a conceptual problem here. Mae has to be coerced by her employer to submit to the Borg, and it’s true that we, too, are driven by compulsion, social anxiety, FOMO, and other unattractive emotions to participate in social media. But The Circle’s satire allows no room for the possibility that people might simply find it fun, useful, and emotionally sustaining to share thoughts, ideas, and images online, and that the pleasure we take in using these tools can coexist, however uneasily, with our knowledge that these are the same tools of cyberbullies and revenge pornographers and ad trackers and the NSA.

The maniacally cheerful and passive-aggressive herd of Circle users with whom Mae constantly interacts are rabid voyeurs, as insatiable for real-time data as the Circle itself, which is precisely Eggers’ point—we are become Big Brother. And The Circle is being published at a terrifying moment when the concept of privacy is becoming close to synonymous with the concept of shame. It’s a zippy, pulpy read that puts pressing issues into sharp relief. But its cautionary tale rests on an underestimation of people’s complicated and idiosyncratic relationships with the Internet and social media. And especially in its last third, which is antic with shark massacre and vehicular mayhem and shocking reveals, it imagines the most malevolent aspects of online life not as byproducts but as goals—the master plans of Dr. Evil–style Internet overlords. There’s a lot of irony to be mined from “Don’t Be Evil.” But rewriting it as “Do Be Evil” gives the tech world too much credit for chutzpah.

—

The Circle by Dave Eggers. Knopf/McSweeney’s.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.