The same week that a statue of Robert E. Lee led to the death of an innocent woman in Charlottesville, Virginia, I watched him oink and squeal in a race for the fate of the country. Lee, this time, was a piglet—part of Dolly Parton’s Dixie Stampede, a Medieval Times–style dine-in attraction where seven nights a week and at occasional weekend matinees, the South rises again.

Advertised as an “extraordinary dinner show … pitting North against South in a friendly and fun rivalry,” Dolly Parton’s Dixie Stampede is the Lost Cause of the Confederacy meets Cirque du Soleil. It’s a lily-white kitsch extravaganza that play-acts the Civil War but never once mentions slavery. Instead, it romanticizes the old South, with generous portions of both corn on the cob and Southern belles festooned in Christmas lights. At its sister staging in Branson, Missouri (the original is up the road from Dollywood in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee), it’s put on at a venue that can only be described as resembling a plantation mansion. Also, everyone in the audience must pick a side.

So when the debate over Confederate monuments reignited earlier this month, I knew I had to see for myself whether this thing was really as tasteless as it seemed. The Dixie Stampede has been running for nearly 30 years, but some informal straw-polling suggests that many casual Dolly fans (including black fans like me) have never heard of it. They might also be surprised to learn that the Union vs. the Confederacy was just the Lakers vs. Celtics of its time.

Because I had seen the promo video on the show’s webpage, I thought I knew what to expect. It all seems innocent enough until you begin to see relics of the War Between the States: waiters dressed in Union uniforms dropping food on the plates of happy patrons hungry for nostalgia and smiling men on horseback wearing Confederate uniforms. As one colleague pointed out with a mix of horror and delight, recalling the deliberately offensive fictional musical from The Producers, it’s Springtime for Hitler.

Update, Aug. 24, 2017, at 2:45 p.m.: The Dixie Stampede’s YouTube page has removed the promo, but here is an audience-captured video from 2015 of the Confederate army riding out to cheers and snippets of the minstrel song “Dixie.”

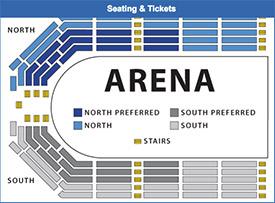

First, though, I’d have to order my ticket, and any visitor to the Dixie Stampede is greeted first with a choice: Do you want to sit with the North or the South? As the granddaughter of a couple who left openly hostile racism in Mississippi and headed north more than 60 years ago, vowing never to live in the heart of Dixie again, my first instinct was, naturally, to sit with the North. (On the seating chart, it was helpfully color-coded blue, the hue used by the Union Army, while the South is assigned a Confederate gray.) But for the sake of journalism and in the tradition of our president, I knew I had to see it “on many sides.” First I’d see the 6 p.m. show with the North and then, later that night, the 8:30 p.m. show with the South.

Dixie Stampede

When I arrived at the Pigeon Forge theater the next day and gave the cheery woman at the box office my name so I could pick up my tickets, she was at first confused. “It appears there are two Aisha Harrises who bought tickets,” she said. Sheepishly, I admitted that it was I who was about to consume two enormous meals in one evening, back to back, by myself. “I’m getting the full experience,” I chuckled. She graciously chuckled back and then explained that at 5:15 there was a pre-show that I shouldn’t miss.

Around 4:30, the crowds began to roll in, dressed as though they were going to spend a leisurely couple of hours at a baseball game, which was fitting considering the show’s theme of “friendly competition.” Still, most people seemed to be with their families or a church group, and I unsurprisingly stood out in my singleness.

Not to mention my blackness. I was surprised to see more people of color than I expected—an Asian family here, a Latino family there. There were smatterings of black people, though I didn’t spot any who appeared to be there by themselves. Some were one half of an interracial couple, while others appeared to be there with their white co-workers or friends. Such is the appeal of Dolly, it would seem, that it crosses all racial borders.

Standing in front of the box office were two young women who looked like the cast of The Beguiled, or Southern belles from Gone With the Wind, greeting patrons as they made their way into the building. Once inside and past the ticket scanners, you were forced to take a group photo in one of several partitioned quarters in front of a green backdrop. Rather than immortalizing this unwanted re-enactment in the form of a $30 souvenir, I asked not to have my picture taken and hurried past while trying to blend in with the family in front of me.

This is when I entered the Dixie Belle Saloon. This two-story hall was the home of the pre-show, with long dining tables on the bottom floor and a small raised stage in the middle. I immediately headed to the bar.

Somewhat to my surprise, a couple of black women were working behind the counter. “Oh, we don’t serve alcohol,” one of the women informed me matter-of-factly. (I later learned that they don’t want it to interfere with Dolly’s “wholesome image.”) My heart dropped and my face twisted up as the prospect of experiencing more than five straight hours of proud Southern denialism sober became all too real. What kind of saloon was this, anyway?

I ordered a lemonade, which came served to me in a white, plastic collectible boot. When I joked to the woman behind the counter that I wasn’t expecting to see so many black people here, she laughed. “We get a few,” she told me, “but not many.”

I took a sip of the too-sweet lemonade, found an open spot at the end of a table, and waited for the pre-show to start. A pair of older white couples sat down across from me, and after they asked me to take a picture for them, we struck up a friendly conversation. They were friends, one couple from Ohio, the other from South Carolina, and the latter had seen the show four times. They were fans of Dolly and country music, they explained. The husband reminded me that there used to be a Dixie Stampede in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, though it has been replaced by a Dolly-affiliated pirate-themed show. The couples had gotten tickets in the sections that corresponded to their respective states, though they hoped to find a way to sit together anyhow.

When the pre-show finally began, so did the hokum that would define the rest of the night. Two men on guitar and one on banjo exchanged corny, “down home” banter onstage in between earnest songs about “going back to Dixie” and “my window facing south,” a medley of Dolly’s signature hits (complete with some horn-tooting about her philanthropy), and Top 40 hits such as “Uptown Funk,” countrified. Everyone around me seemed to really enjoy it. When the trio performed an up-tempo version of “Amazing Grace,” the audience decided to clap along. They were very off-beat.

When the pre-show concluded, we were all herded upstairs into the recently renovated 1,100-seat horseshoe-shaped theater, which was almost entirely full at both performances I attended. Once seated in the North section, second row from the back, our peppy waitress Jan greeted us, explaining that everything in the menu printed on our napkin would be served to each of us over the course of the show: a whole rotisserie chicken, smoked pork loin, vegetable soup, a biscuit, corn on the cob, a potato, and a pastry dessert. She also explained that Dolly’s Dixie Stampede had no use for utensils—we had to eat everything with our hands (and drink the soup from the bowl).

I asked Jan what was supposed to be the difference between the North and the South. “Nothing. The colors,” she replied cheerfully, pointing out her costume. To my surprise, the North side waiters were not dressed like Union soldiers as in the promo video I’d seen. Instead, they were wearing dark blue long-sleeve shirts and bottoms, with white and gold trim. On the South side, the servers wore the same suits in gray with red trim. “It’s a competition!” she added. “Some people really want to sit on the South side, and some really want to be on the North.”

Finally, the main event got underway with a pre-recorded message from Dolly inviting us to enjoy her Dixie Stampede. A man emerged on horseback in an all-white cowboy outfit and introduced himself as Roger Ballard, our host, explaining that the reason we were all here was to “settle an age-old rivalry” between two regions of the United States. In his Southern drawl, he laid down the rules and told us exactly how to feel about the opposing side: The North was to consider the South “a bunch of flat-headed, narrow-minded, short-sighted feather brains” and encouraged us to heckle them when the occasion called for it. Ditto the South side, which was to think of the North as “foul-smelling” and “gold-digging.” He broke into song, crooning about it being “a time for choosing sides” before introducing individual performers who would be competing in a series of games for each side as they rode their horses into the arena.

Before we could get to the games, though, we had to get through a little “history” lesson about the early days of America, beginning with live buffalo and “Native Americans.” Were the dancers and acrobats actually of Native American descent? It was hard to tell, as their performance took place entirely under black light to the tune of Parton’s 2009 song “Sha-Kon-O-Hey!” (The title of the song is intended to be a phonetic spelling of the Cherokee word for the Smoky Mountains.) As one of them flew through the air on cables, a pre-recorded voice-over described the indigenous peoples as “steeped in legend … mystery … and magic!”

Dixie Stampede

At the dance’s conclusion came a swift scene change: “The magic gave way to a harsh reality when settlers came in from the east.” In one of the more true-to-history moments in the show, these native peoples weren’t seen again for the rest of the performance.

Instead, the settlers quickly colonized the arena, riding horse-drawn covered wagons and lip-syncing about the wonders of new frontiers. l spotted two black female chorus members among the ensemble dancing and singing side-by-side with the white chorus members, and when the women and men paired up, they even danced with the white male dancers. Everyone seemed to be getting along just fine. (“Look at that, we had the North and the South dancing and happy together!” Roger Ballard was sure to note at one point later in the evening.) As a musical number about cooking a meal over open fire filled the air, the food—which, I should say, was not bad, but not quite Cracker Barrel—was quickly and efficiently delivered.

The story of westward expansion soon gave way to the show’s centerpiece: the battle between North and South. The field of battle? Games, in the style of both the circus and the county fair: balloon popping (on horseback), a chicken race, a pony race, a pig race, a water bucket race, and a horseshoe competition using oversized toilet seats. On more than one occasion, the South was a particularly good, and even generous, sport: When the North was defeated, the South would sometimes give them a do-over. Even with that gracious assistance, however, the South won at both my performances. (According to reports from other attendees, the South doesn’t always win, but it usually does.) All the while, Roger Ballard would alternate between extolling the virtues of both sides and encouraging them to stand up and boo one another. (At both shows I attended, the South was noticeably more boisterous in its heckling.)

Of course, this was not Dolly’s Yankee Stampede, but Dolly’s Dixie Stampede, and the South was given the most spotlight. For comic relief, a country bumpkin named Skeeter would pop on stage from time to time to prank the host and make jokes about Walmart. Ballard introduced a dance number—in which those Christmas light–adorned Southern belles gallivant under a pavilion to a song referencing Dixie—by waxing nostalgic: “It truly was a time of chivalry and romance, almost as if it were a fairytale.”

While the show makes zero mention of slavery, that’s not to say there were no references to the Civil War. The war was alluded to both in the overarching North-versus-South conceit and through details both subtle (the gray and blue color schemes on each side) and blatant: The racing piglets were named after Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, and Scarlett O’Hara. Dolly says that the show is about bringing back “those good old times,” referring to her childhood, but of course she wasn’t around during the days of Grant and Lee.

The final competition got the entire audience involved: Each row was instructed to pass a flag as quickly as they could until it reached the other end of their section, and whichever side got all their flags down first won. But as Ballard explained when it was over, it didn’t really matter because there “really is no North or South,” “we’re all winners,” and “we’re all under one flag: the United States of America.” (Many sides!) Then, for the grand finale, the ensemble, covered in sparkly red, white, and blue costumes that lit up, came out to perform to Dolly’s stirring ballad, titled “Color Me America.”

Recognizing that I now had to do it all again from the perspective of “the South,” I briefly contemplated dashing to a nearby liquor store to procure some shooters to sneak in—but I soon realized I didn’t have time before the next show began. I did at least have time to run to the bathroom—a necessity after three and a half hours of sucking down lemonade by the bootful. This seemed like it could be a nice break, but when I got there, I stumbled upon this:

Aisha Harris

“Southerners Only” on a light-colored placard and “Northerners Only” on a dark-colored placard.

This was, at best, horrifyingly tone-deaf, but I went in the “Southerners Only” stall anyway because it was the only one open and my bladder felt ready to explode.

From there, much was the same save for a few details. The host’s name was now T.C., not Roger (though I honestly couldn’t tell whether it was a different performer or not). I blushed a bit as I asked the same workers once again not to have my picture taken. Perhaps more significantly, this time I didn’t see any other black people on my side, though I did spot an Asian family of at least seven people, most of them young kids, a row behind me. Also, if I was hesitant to cheer and otherwise engage in audience participation when sitting in the North section, I absolutely refused to do so when sitting in the South. I even contemplated hijacking the flag relay so that our side couldn’t win, but then I remembered I was one black person among hundreds of white people in a place called “Dixie Stampede” in 2017, and I emotionlessly passed the flag without a fuss.

As the crowd began to disperse, I chatted up the white couple next to me. They happened to be from Staten Island, in my hometown New York City, and looked to be in their late 20s or early 30s. They were there as fans of Dolly. I asked, “What do you think of the fact that in the show they claim ‘we’re all winners’ and ‘there’s no North and South,’ considering everything that’s happening in the news lately?” The guy leaned in slightly with a gleam in his eye: “Look, it’s all bullshit,” he said. “But that’s the way it is down here.” If this show were being performed in New York, he said, he’d think it was weird. He then proceeded to tell me that he didn’t vote in the last election (“Trump sucks, Hillary sucks, and I knew Hillary was going to win my state, so it didn’t matter”) and bemoaned how we’re all ignoring the “real problem”—religion—and are too afraid to call other cultures out for the terrorist attacks happening around the world.

The way he dismissed the homegrown terrorism that had occurred within our country just days before crystallized something for me. Dolly’s Dixie Stampede has been a success not just because people love Dolly Parton, but because the South has always been afforded the chance to rewrite its own history—not just through its own efforts, but through the rest of the country turning a blind eye. Even though the South is built upon the foundation of slavery, a campy show produced by a well-meaning country superstar can make-believe it’s not. We’d prefer to pretend, to let our deepest sins be transmuted into gauzy kitsch—and no one blinks an eye because that’s what they truly want.

So while it may be a surprise to the fictional producers of Springtime for Hitler when it becomes a hit, it’s no surprise to me that Dolly Parton’s very real Dixie Stampede is a hit, too, and has been for almost 30 years. This is the same country where The Birth of a Nation was once the biggest box-office hit of all time and where Gone With the Wind still is. Dolly Parton is right about one thing: Dixie Stampede is as American as America gets.

Just look at the reviews. “The only suggestion I have is to cut out the part where they talk about the ‘cotton plantation’ and how gracious it was,” complains one visitor to the Pigeon Forge show on TripAdvisor. “This is 2015 and it’s just not tasteful any more to refer to mint juleps and southern belles when those plantations were places of such terrible suffering for so many people.” She also complimented the stunts and the food, headlining her review, “Trick riders! I ate a whole chicken!” Like most reviewers, she gave it five stars.

Update, Sept. 13, 2017: A spokesman for Dolly Parton’s Dixie Stampede has responded to this review in a statement.