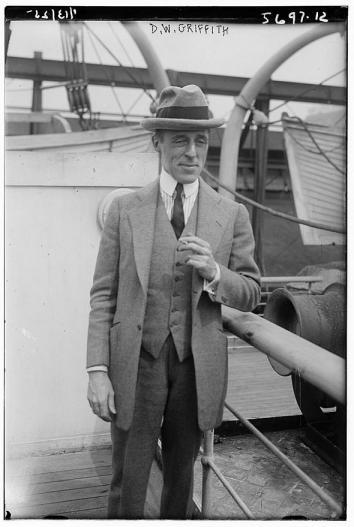

In 1916 a 41-year-old man in Los Angeles published a short pamphlet called “The Rise and Fall of Free Speech in America.” In passionate if somewhat pompous tones, the author described motion pictures as “the laboring man’s university,” but warned that their power to educate and instruct the nation could be “muzzled by a petty and narrow-minded censorship” that would create “a sugar-coated, virtuously-garbed version … in order to satisfy the public mentors of our so-called morals.” He quoted dozens of journalists and politicians who opposed censorship, cited Shakespeare and the Bible for good measure, and protested that “this new art was seized by the powers of intolerance as an excuse for an assault on our liberties.”

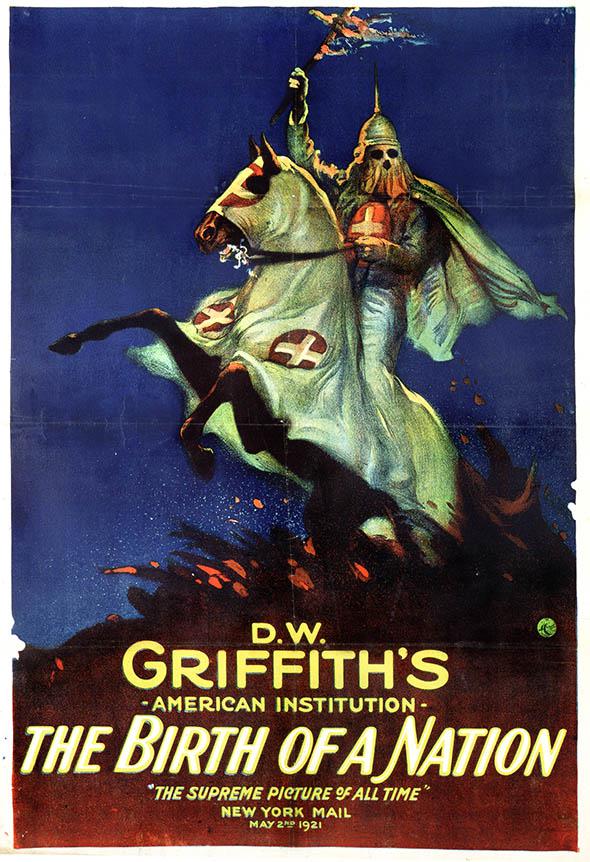

The pamphlet’s author was the film director D.W. Griffith, and the subtext for his First Amendment flag-waving was the fierce campaign against his 1915 motion picture The Birth of a Nation. The longest and most expensive movie yet produced was an unprecedented box office phenomenon: Griffith biographer Richard Schickel estimates that by the end of 1917 it would gross $60 million, an unheard-of sum. But it was also hated like no picture before or since for its grotesque distortion of Reconstruction, in which black characters are sexual predators and vengeful thugs, former slave owners are persecuted victims, and members of the Ku Klux Klan are gallant saviors. Roy E. Aitken, one of the film’s producers, described The Birth of a Nation as “the most controversial film in America.”

Photo by John D. Kisch/Separate Cinema Archive/Getty Images

A century after its release, that controversy is long dead. Film studies professors preface their lectures on the film with emphatic disclaimers about its politics, then teach it anyway because of its multiple breakthroughs in the use of editing, cinematography, and music. No serious critic would disagree with James Baldwin’s assertion in The Devil Finds Work that the film is both “one of the great classics of the American cinema” and “an elaborate justification for mass murder.” Like Triumph of the Will, it is a technical tour de force and a moral pariah, one that vividly illustrates the racist mindset: violent, paranoid, sexually neurotic, sentimental, and absurd.

But only one argument—the one between the filmmakers and their opponents—has been settled by history. The rupture inside liberalism, about whether any work of art can be dangerous enough to merit suppression, has never been resolved. Some liberals believed that Birth’s distorted history had such menacing implications for black Americans that they forged awkward alliances of convenience with reactionary forces who wanted to manacle cinema itself. Meanwhile, free-speech hard-liners on the left loathed the picture and efforts to prohibit it in equal measure. In his authoritative history, D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, Melvyn Stokes quotes Chicago journalist William L. Chenery: “Liberals are torn between two desires. They hate injustice to the negro and they hate a bureaucratic control of thought.” The Birth of a Nation didn’t just transform cinema forever; it inaugurated a debate about art, race, and freedom of expression that shaped American history.

* * *

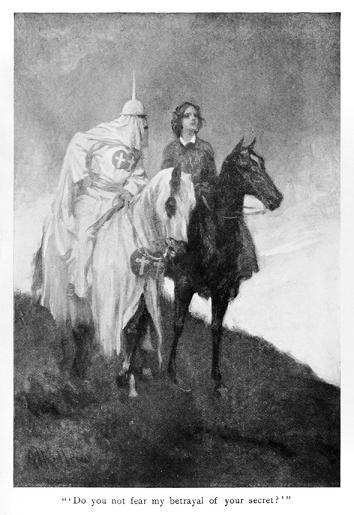

Illustration by Arthur I. Keller/Documenting the American South

The Birth of a Nation might never have existed without Uncle Tom’s Cabin. One evening, around the turn of the century, writer and lecturer Thomas Dixon, Jr. attended one of several stage adaptations of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s blockbuster abolitionist novel. Dixon was a wealthy former actor, state legislator, and Baptist minister from North Carolina, and a virulent racist. The play left him weeping over the misrepresentation of his beloved South.

His counterblast was the Reconstruction Trilogy, a clumsy, didactic melodrama driven by his hysterical phobia of interracial relationships and a belief that “the conflict between the two races is absolutely irreconcilable.” Taking place in North and South Carolina just after the Civil War, The Leopard’s Spots (1902), The Clansman (1905), and The Traitor (1907) all combined love stories with valorisation of the Ku Klux Klan and indigestible clumps of racist polemic. The villains of The Clansman, all of whom would appear in the most contentious parts of Griffith’s film, were abolitionist Rep. Austin Stoneman (a thinly veiled Thaddeus Stevens), his mixed-race protégé Silas Lynch, and the former slave Gus, who is executed by the Klan after causing the death of a white girl. “My sole purpose in writing was to reach and influence with my argument the minds of millions,” Dixon wrote in his autobiography.

Dixon quickly merged elements of the first two novels into a play called The Clansman (1905), with the black characters played (as they would be in the movie) by white men in blackface. In American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon, Anthony Slide explains that Southern newspaper critics and clergymen were shocked by its racism, describing it as “a riot breeder” and “about as elevating a lynching,” even as white audiences lapped it up. When it traveled north, a massive demonstration by black protestors in Philadelphia led the mayor, fearing a riot, to ban the play.

Photo by Bain News Service/Library of Congress

In 1913, Dixon sold the motion picture rights to D.W. Griffith, a wildly ambitious and prolific director who, as the son of a former Confederate officer, shared Dixon’s view of Reconstruction as a crime against the South. What really stirred his blood, though, was Dixon’s description of the Ku Klux Klan riding to the rescue of persecuted white Southerners—an image he believed was crying out for the big screen. The Clansman began shooting on Independence Day 1914 and was scheduled to open in Los Angeles on Feb. 8, 1915.

The local branch of the NAACP, however, had other ideas. Dixon’s previous work was so notorious that the civil rights group tried to have The Clansman (it was retitled shortly afterward) banned before having seen it. When the members arranged a screening on Jan. 29, their fears were confirmed. It was, they claimed, both “historically inaccurate and, with subtle genius, designed to palliate and excuse the lynchings and other deeds of violence committed against the Negro.” They sought to have it barred on the grounds of public safety. When their efforts failed, they urged the NAACP’s national headquarters in New York to take up the fight.

* * *

The office building at 70 Fifth Ave. in New York City housed two fledgling organizations, both formed in 1909. One was the NAACP. With just 5,000 members and scarce resources, it had so far been too busy on multiple fronts—voting rights, employment opportunities, desegregation, anti-lynching laws—to worry about motion pictures. The other was the National Board of Censorship, a private body embraced by the film industry to ward off demands for a government equivalent. The board had already approved Birth, but the NAACP persuaded it to reconsider.

In 1915 moral panic over the depiction of crime and vice in such movies as Traffic in Souls and The Inside of the White Slave Traffic was feeding conservative demands for constraints, with Congress already mulling a federal censorship board. The most successful legislation to that point, a 1912 bill to ban interstate sales of boxing films, had a blatantly racist motive: the desire to suppress footage of boxer Jack Johnson defeating “great white hope” James Jeffries. Free-speech advocates fought back against the rising tide. Vetoing an ordinance to introduce movie censors in New York City, Mayor William Jay Gaynor wrote, “Do they know what they are doing? Do they know anything of the history and literature of the subject? Do they know that the censorships of past ages did immeasurably more harm than good?”

Photo by Museum of the City of New York/Byron Co. Collection/Getty Images

But in February 1915, just as Birth was making its way into theaters, filmmakers were dealt a serious blow by the Supreme Court. In Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, the court ruled that movies were not worthy of the same free-speech protections as the printed press. The ruling, which prevailed until 1952, gave the green light for states to create their own censorship bodies. In his majority opinion, Justice Joseph McKenna ruled that moving pictures were “capable of evil, having power for it, the greater because of their attractiveness and manner of exhibition.”

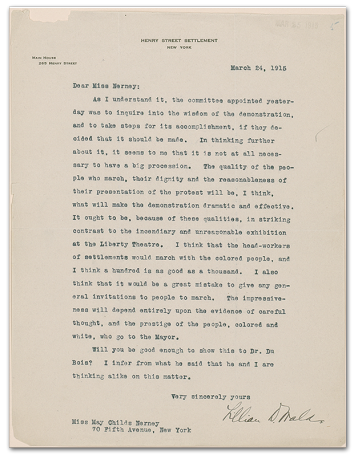

The NAACP’s anti-Birth forces were spearheaded by its national secretary, May Childs Nerney. The association’s white-dominated leadership was divided, with some members worrying that the fight was a poor use of limited resources, but Nerney, who was also white, believed that opposition was essential. “If it goes unchallenged it will take years to overcome the harm it is doing,” she wrote in a memo. “The entire country will acquiesce in the Southern program of segregation, disenfranchisement and lynching.”

Nerney was a versatile pragmatist, willing to try anything. She compiled campaign dossiers for local NAACP branches, quoting high-profile allies such as novelist Upton Sinclair, who called the film “the most absolute terrifying and poisonous play that I have ever seen” and predicted that screenings in the South would provoke “a hundred thousand murders.” When the New Republic critic Frances Hackett condemned Griffith’s picture as “a spiritual assassination [that] degrades the censors that passed it and the white race that endures it,” Nerney mailed copies to 500 newspapers. By the end of April, the outcry was so effective that President Wilson, who had screened the film at the White House as a favor to his old college friend Dixon, denied that he had ever approved this “unfortunate production.”

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Another idea was to fight art with art by producing a film that celebrated black progress. Perhaps, suggested Booker T. Washington, this “counter-irritant” could be based on the inspirational autobiography of Booker T. Washington. The NAACP, meanwhile, collaborated with Carl Laemmle’s Universal on a screenplay called Lincoln’s Dream. But neither project materialized as hoped.

On-the-ground protest was also attempted. In Boston the formidable activist William Trotter mobilized the black community to stage pickets and marches, in its biggest show of strength since the Civil War. But the NAACP leadership fretted that public protest would give Birth free advertising, which made the quieter route of censorship more appealing. They weren’t always candid about their embrace of censorship, however. An NAACP report stated that “All forms of censorship are dangerous to the free expression of art,” but noted that where bodies tasked with exercising censorship already existed, “it was our right and duty to see that this body acted with fairness and justice.” Yet the organization sometimes actively campaigned for new legislation, including the controversial Sullivan Bill, which one Boston paper claimed would “assassinate dramatic art in Massachusetts.” Where state boards didn’t exist or couldn’t be brought into existence, the NAACP used any weapon it could, from pre-emptive use of anti-riot ordinances to laws prohibiting art that was “subversive of public morality.”

At first, all this effort yielded few rewards. The National Board of Censorship reconsidered the film in March but approved it again after successfully requesting cuts to the sequences depicting interracial violence. (According to Jane Gaines in Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era, Griffith was forced to tone down Gus’ pursuit of Flora Cameron, Silas Lynch’s harassment of Elsie Stoneman, and the Klan’s brutal revenge on Gus.) After a year’s campaigning, only Ohio and Kansas had imposed statewide bans. A dejected Nerney resigned.

Even as it faltered, the banning strategy put white liberals in an uncomfortable position. Some, including the celebrated social workers and NAACP co-founders Jane Addams and Lillian Wald, believed that the film was so unusually dangerous that censorship was justified; others refused to make exceptions and felt compelled to defend a film they found loathsome. A column in the Masses, a Greenwich Village radical magazine, agreed that the Birth of a Nation “perverts history, incites race-prejudice and justifies crime,” but deplored efforts to suppress it. “Our censors are getting ‘liberal.’ But there is one more stage of liberality. It is possible to say: ‘We will take the risk of this picture doing harm. We will take the risk of any picture doing harm. We will prohibit nothing.’ That is an honorable, if difficult, thing to say. Let the board of censorship say that, and resign.”

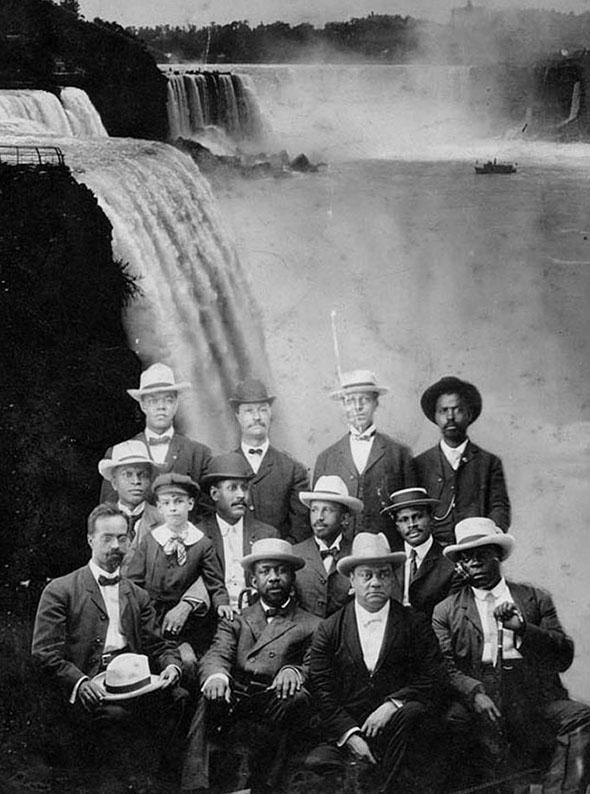

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

You have to wonder if the staff of the Masses would have been so willing to take that risk were they not all white. The harm Birth caused wasn’t measurable, exactly, but it was tangible. True, the worst fears of Nerney and Sinclair were not realized. The film didn’t provoke mass murder or race riots. And Dixon’s hopes that Birth would inspire a new wave of legislation against his bugbear, interracial marriage, were thwarted. But W.E.B. Du Bois, editor of NAACP journal the Crisis, later noted that the number of lynchings in America had risen sharply in 1915. In Lafayette, Indiana, a white man walked out of a screening of the movie and shot dead a 15-year-old black high school student.

Birth was also inextricably linked with the return of the Ku Klux Klan, relaunched by Alabama teacher William J. Simmons in 1915. The new Klan based its logo of a horseman with a burning cross on a still from the movie and made its first public appearance outside the Atlanta premiere. The film’s publicists cashed in by manufacturing Klan merchandise, including hats and aprons, and hiring hooded horsemen to promote screenings. Membership didn’t spike until the Klan launched a professional recruitment drive in 1921, after the film’s popularity had peaked, but Simmons claimed Birth had “helped the Klan tremendously.”

Regardless of its wider influence, the movie itself had a traumatizing effect on black viewers. The actor William Walker, who later played the Rev. Sykes in To Kill a Mockingbird, saw it in a segregated theater where audience members cried and cursed. Interviewed for the 1993 documentary D.W. Griffith: Father of Film, he recalled: “You had the worst feeling in the world. You just felt like you were not counted. You were out of existence.”

For all these reasons, and despite some reservations, Du Bois felt that censorship was justified. Writing to the head of the NAACP in 1921, he called The Birth of a Nation “a special case. A new art was used, deliberately, to slander and vilify a race.” To Du Bois, it was “a public menace … not art, but vicious propaganda.”

Photo via Creative Commons

Dixon agreed that Birth was propaganda. That was the point of his entire writing career. Fighting a Vicious Film: Protest Against The Birth Of A Nation, a pamphlet published by the NAACP’s Boston branch, included an editor’s account of a visit that Dixon paid to the offices of the Congregationalist and Christian World. Dixon said “that one purpose of his play was to create a feeling of abhorrence in white people, especially white women, against colored men … to prevent the mixing of white and Negro blood by intermarriage,” and added “that he wished to have all Negroes removed from the United States.” While Griffith sought the high ground of art and what he claimed to be historical accuracy, Dixon essentially admitted that it was hate speech. The case for censorship hinged, in part, on whom you believed.

Du Bois concluded his memo: “We are aware now as then that it is dangerous to limit expression, and yet, without some limitations civilization could not endure.”

* * *

In 1916, D.W. Griffith released his latest epic, Intolerance, a defense of free speech that some viewers misinterpreted as an apology for Birth. Floyd Dell of the Masses was impressed. “There is, perhaps, something ironic in the idea of the producer of that hate-breeding film-play, ‘The Birth of a Nation,’ telling us to be tolerant. But it is not more ironic than the spectacle which some of us haters of censorship furnished when we tried to stop its production—and left a trail of film-censorships in our wake which it will take twenty-five years to abolish!”

Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images

As it turned out, events beyond the NAACP’s control swung the censors in their favor. During World War I, several states quashed Birth lest it foster animosity between white and black soldiers. After the war, the dramatic rise and fall of the new Klan (which Dixon, ironically, considered “a menace to American democracy” and doggedly opposed) made the movie increasingly toxic. To legislators, a blow against Birth was a blow against the Klan. Simultaneously, a slew of scandals, including the trial of comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle for the rape and manslaughter of actress Virginia Rappe in 1921, persuaded authorities that it was time to crack down on the whole movie industry. The anxious studios reached out to former Postmaster General William H. Hays to help the industry police itself, leading in 1930 to the Motion Picture Production Code, known as the Hays Code.

Courtesy of the NAACP/Library of Congress

Even as the new climate of censorship helped the NAACP in its effort to ban the movie, it had unintended consequences for black representation in motion pictures. As Thomas Cripps explains in Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900–1942, nervous studios shied away from portraying black characters at all and the Hays Code prohibited any portrayal of interracial relationships, positive or negative. In 1920 black director Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates, which excoriated lynch mobs and the Klan, was banned in several places for the same reasons as Birth: It could incite racial tension. Thus the weapons taken up against a racist film were turned on an anti-racist one.

Even after the picture had fallen out of favor, Melvyn Stokes explains, the debate rolled on. In 1939 the ACLU opposed a Denver ordinance prohibiting films that encouraged “race prejudice” and told the NAACP that such laws “are inevitably a boomerang. The precedent established will work against films favourable to Negroes, opposed by the other side.” In 1950, Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and future Supreme Court justice, took a similar line in a memo to the editor of the Crisis, wondering how the association could continue to fight to censor Birth while opposing Southern restrictions on movies that portrayed black characters positively. Pickets and demonstrations, he argued, were valid tactics, but “when we get to the question of governmental censorship, we get into an awfully tough problem.”

By this point, both proponents and opponents of bans could claim to be vindicated. If the NAACP had never campaigned at all, it would have missed a golden opportunity to grow its nascent organization. Membership doubled to 10,000 by the end of 1915 and had reached 80,000 by the close of the decade. The NAACP established a strong national network, pioneered direct-action tactics that would bear fruit in the civil rights movement, and emboldened black activists to make other demands. It galvanized anti-racists, shone a light on race relations in every city that considered whether a movie could trigger a riot, and forced even publications that abhorred censorship to decry the movie, often for the first time.

But imagine a counterfactual. What if the NAACP had succeeded in blocking the release of The Birth of a Nation at the very start? The activism, the organizational breakthroughs, the vigorous national debate that extended from the streets to the White House, would not have happened, and Griffith and Dixon might have become free-speech martyrs. The NAACP’s initial inability to get Birth banned felt like a demoralizing defeat, but its subsequent campaign achieved what censors meeting behind closed doors could not. In failing to silence the movie, the protesters gave themselves a megaphone and made a mighty noise. In losing the first battle against Birth and its toxic version of American history, they won the war.