In his entry to Alain Locke’s 1925 The New Negro anthology, Arthur Schomburg described the black American past as a patch of untilled soil that the “Old Negro” had been content to stand upon rather than cultivate. Titled “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” Schomburg’s essay argued that black America’s arrival as a modern people—and a new generation’s decisive break from the stereotypes associated with its forefathers—depended upon a new relationship to the past. The past should no longer be thought of as an inert, constricting burden, but a malleable resource.

Near the end of Raoul Peck’s new documentary I Am Not Your Negro, James Baldwin (via the voice of actor Samuel L. Jackson) also speaks of the past, intoning that history “is not the past. History is the present. We carry our history with us. To think otherwise is criminal.” Speaking as he does through Jackson, we might think that Baldwin is describing history’s inescapable purchase upon black life. We wouldn’t be wrong, but I suspect that Baldwin intended that statement in the same spirit that moved Schomburg: History is not immutable, a fate to which we must all eventually succumb. Rather, it is a practice we always conduct in the present tense, reshaping the past in order to imagine desired futures.

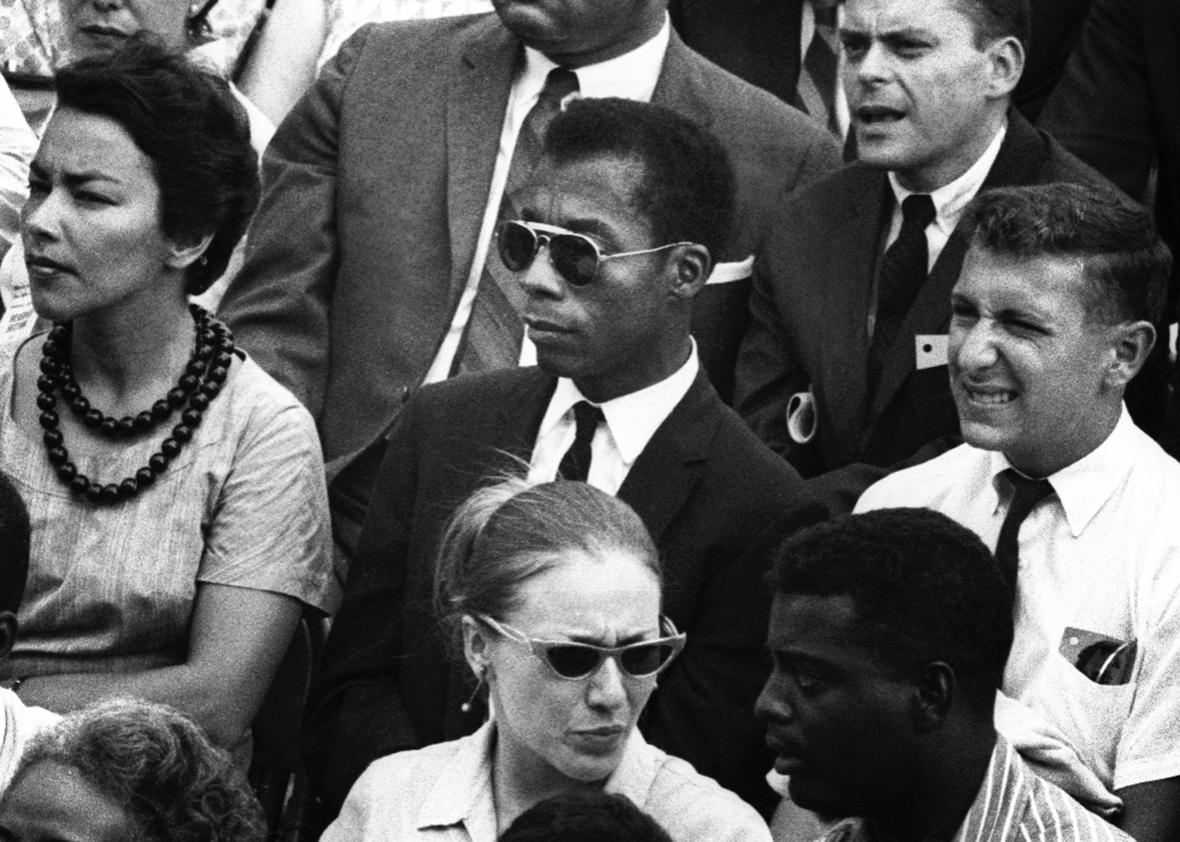

I had the sense, while watching I Am Not Your Negro—based on notes that James Baldwin prepared for an unfinished memoir titled Remember This House—that Peck had borrowed Baldwin’s stance. He stages an encounter between the past and present, an exchange between two voices that produces something new. The film interweaves archival footage of the Civil Rights Movement and Baldwin’s television appearances, contemporary images of protests and police violence in Ferguson, and original material into a volatile collage. But rather than erasing distinctions between the past and present, I Am Not Your Negro gestures toward a disjunction between Baldwin’s moment and our own. Peck’s decision to have Samuel L. Jackson narrate the movie, for example, points to an antiphonal ethos: It structures its relationship with Baldwin as a conversation that might produce new knowledge. We hear Jackson reading Baldwin’s unfinished project, as if Jackson and Peck were helping the dead writer finish a thought he couldn’t quite complete. In finishing that thought, Peck also allows a new, composite voice to come to the fore. The film asks us to ponder what we can know about our contemporary moment when we stop ventriloquizing our ancestors, and begin to speak in our own voices.

This idea challenges a thesis that writers such as Michelle Alexander have made into a commonplace in contemporary analyses of black life: Black people are merely living through endless repetitions of slavery and Jim Crow, which white supremacists massaged into subtler forms of control. According to this thesis, black Americans exist in a moment of foundational violence—slavery—that repeats ad infinitum. This is a traumatic model of black history whose hallmark is a deadening, Oedipal regularity. Each moment fundamentally resembles our forefathers’, and historical change amounts to window dressing. The past and present are drawn into such a claustrophobic embrace that it seems pointless to draw distinctions between the two.

Peck isn’t alone in disputing this theory. With Baldwin as the centerpiece of their inquiry, a generation of black thinkers are contesting this assumption. A proliferation of recent essays, films, and books haunted by Baldwin—from Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me to Jesmyn Ward’s recent essay collection The Fire This Time—attests not only to his renewed relevance, but also to his particular usefulness for challenging the logic of perpetual trauma.

But much of the criticism that’s been written about this cohort of contemporary black writers illustrates a general tendency to mischaracterize Baldwin’s influence. Reviewers greeted Between the World and Me, for example, with an Oedipal wave hellbent on adjudicating whether or not Coates is Baldwin’s legitimate heir. Toni Morrison—whose classic novel Beloved popularized the notion of a traumatic black history—unambiguously cast Coates as Baldwin’s literary son. Cornel West, contrarian as ever, wrote that Coates is merely a “clever wordsmith with journalistic talent” who doesn’t live up to Baldwin’s revolutionary legacy. Taking, perhaps, another chance to needle West, Michael Eric Dyson delivered a precise analysis of Coates and Baldwin’s prose styles, concluding that “if Baldwin couldn’t be Baldwin now, he’d more than likely be Coates, or somebody like him.” Meanwhile, Vinson Cunningham marshaled eloquent close readings and a strong command of American literary history to argue that Baldwin and Coates diverge over their investment in religion, with Baldwin playing the committed Christian preacher to Coates’ clear-eyed atheist rapper.

No matter what particular arguments they were making, they were all operating on the premise that Coates’ formal proximity to Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time demands an answer to the question of literary genealogy. Such writings amount to well-written paternity tests concerned with a single, tabloid-worthy question: Who’s the father?

The problem here is that Baldwin—a gay man who had no children—is the last writer one should turn to for an answer to that question. He launched his career via literary patricide, turning on forefather Richard Wright in a cold-blooded (and unfair) display of literary bravura, and his oeuvre betrays a singular skepticism at the very idea of familial lineage. Baldwin’s writing often looks askance at biological family ties, with language that figures generational bonds as a problem, laden as they are with oppressive histories. These bonds always threaten to become chains for Baldwin, and lineage seems coextensive with numbing repetition.

His essays propose a queered definition of reproduction, one loosed from the Oedipal rhythm embedded in the question of lineage. In “My Dungeon Shook,” the first essay from The Fire Next Time, Baldwin pens a letter to his nephew and namesake James. “I keep seeing your face, which is also the face of your father and my brother,” he writes. “Like him, you are tough, dark, vulnerable, moody … You may be like your grandfather in this, I don’t know, but certainly both you and your father resemble him very much.” From the essay’s beginning, Baldwin weights his language with a sense that the paternal relationship means incessant reiteration.

His letter is an interruption in this line of descent, a familial relation not premised on the paternal. It’s certainly intended to disrupt James’ otherwise inevitable inheritance of his forefathers’ passive acceptance of received roles. If the grandfather “was defeated long before he died because, at the bottom of his heart, he really believed what white people said about him,” Baldwin arrives on the scene to teach his namesake that he must craft an identity separate from the caricature—the nigger—that white America has reserved for him. Baldwin insinuates that there’s a queer aspect to the very act of writing, a self-fashioning that cuts against history’s necessities. The younger James—named, crucially, after his writer uncle rather than his father—must shirk Oedipal logic if he is to slip white supremacy’s grip. Surviving as a black boy in America means shedding your father’s assumptions and taking up the burden of self-fashioning.

If some contemporary black writers are drawn like moths to The Fire Next Time, it’s because they sense something important in this exit from repetition, this call to fashion the black self anew. This is what is missing from the attempts to verify Coates’ status as Baldwin’s heir: The turn to Baldwin is not an act of reverence or restatement of knowledge that Baldwin already gave us. For writers like Coates, Ward, and Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, Baldwin is a specter that elicits an ambivalent mix of veneration and trepidation. This ambivalence is an occasion to strain against a traumatic model of history. Rather than taking that thesis as a given, they interrogate it, forcing us to consider how black people can learn from the past without uncritically accepting our ancestors’ fears, assumptions, and intellectual legacies. They want to acknowledge the long shadows that slavery and Jim Crow cast on our present without standing in them. We might think of these writers as among a school of black nonfiction writers for which Baldwin is a problem as much as an interlocutor, a specter to which they return cyclically—almost compulsively—to both honor and decline. But by discussing these texts mostly in terms of how similar they are to Baldwin, or whether or not they’re deserving of Baldwin’s mantle, certain critics have committed the exact mistake that these works struggle to avoid—collapsing distinct historical moments into one.

If we’re just talking literary form, such criticism ignores these texts’ striking aesthetic feats. These feats enact a tortured ambivalence toward Baldwin that simultaneously instantiates and interrogates the history he represents. In her introduction to The Fire This Time, for example, Jesmyn Ward describes the experience of Trayvon Martin’s death as the latest episode of a recurrent nightmare. “Replace ropes with bullets,” she says. “Hound dogs with German shepherds. A gray uniform with a bulletproof vest. Nothing is new.” For Ward, every aspect of contemporary life has a corollary in the Jim Crow past. Her litany of substitutions creates a time warp, casting the reader into a perpetual moment of oppression. White supremacy might have swapped guises, but its power remains interminable and total.

It’s no surprise that, in the aftermath of Martin’s death, Ward returns to Baldwin with an eye toward the same cyclical regularity of racist violence. Reading The Fire Next Time’s first essay, “My Dungeon Shook,” she finds such solace that she inserts Baldwin into her family tree, literalizing his status as a literary ancestor: “It was as if I sat on my porch steps with a wise father, a kind, present uncle, who … told me I was worthy of love. Told me I was something in the world. Told me I was a human being. I saw Trayvon Martin’s face, and all the words blurred on the page.” On the one hand, Ward’s citation of Baldwin’s enduring prescience becomes a measure of America’s static racial politics. He continues to be necessary because the conditions he describes still exist, and his writings become immutable truths.

But Ward’s fantasy of Baldwin as father throws a bit of a wrinkle into her explicit pessimism. What does it mean to claim a man who disdains the very notion of descent as a father? To write in Baldwin’s wake means to displace the father-teacher in a Whitmanesque act of parricide—not to dutifully shoulder the same historical burdens, but to comprehend one’s own historical moment more clearly. Perhaps this is why, even as Ward honors Baldwin, his words must recede into the background, blurring on the page as Trayvon Martin’s face takes precedence. It’s this blurring that informs Ward’s act of writing and her impulse to gather a generation of writers in whom readers might find not fathers, but “a wise aunt [or a] more present mother.” This is an exit from Oedipal logic, a break in the chain, and Ward goes to Baldwin because he allows for this. As Ghansah writes in her contribution to Ward’s collection, “The Weight,” Baldwin left no heirs—only spares, people who might one day take his place.

The same acknowledgement motivates Coates’ use of the letter conceit in Between the World and Me. The very act of writing the letter to his son Samori represents a conscious break from the past, or at least an attempt to feel for possibilities beyond it. Coates is not just repurposing an old literary conceit; he’s also employing the skepticism toward lineage that the conceit implies.

Reflecting on his time in Paris (Baldwin’s echo abounds), Coates recalls a “wholly alien” sense that he is finally “far outside of someone else’s dream.” This experience awakens him to a state of flux that he recognizes as life’s defining fact, a fact that he realizes only when he leaves America behind—and begins to glimpse a life that isn’t shot through with the perpetual sense of anxiety, fear, and anger that white supremacy has imparted to him. Though Coates knows that he is too close to America’s racist past to ever move beyond the behaviors it has instilled in him, the literary form of the letter becomes a space wherein this interruption in racist violence’s damage might persist—and be passed on to his son in lieu of a traumatic inheritance.

Coates later returns to Paris, this time with his son in tow. “I wanted you to have your own life, apart from fear—even apart from me,” he tells Samori. “I am wounded. I am marked by old codes, which shielded me in one world and chained me in the next.” This is the threat that Coates strains against throughout this book: not only the threat of being chained to outmoded and myopic assumptions, but also of passing his own wounds on to his son. Reading this sentence, it’s easy to be reminded of Baldwin’s letter to his nephew. Baldwin intervened in the Oedipal cycle because he feared that generational bonds would become mental chains, and Coates has learned the lesson. Having a life apart from history’s wounds necessarily entails a life apart from the father and his assumptions, and while Samori might take up the fight against white supremacy, his fight will not be Coates’.

Rather than turning Samori into an heir, Coates wants his son to take stock of what has changed between their two historical moments—not because white supremacy has evaporated, but because taking account of change allows one to cast about for the hollows and gaps that black struggle has hacked into white supremacy’s edifice. The letter framing speaks to Coates’ hope that his son’s past will be fertile ground to cultivate, a valuable resource we may tap in order to better perceive our present, carrying forward what is useful and laying down what is not. To think otherwise, as Baldwin might say, would be criminal.