Do we ever understand those we love? What price do we pay to know them? These are the questions at the heart of Daniel Clowes’ new comic Patience, his first major release in almost five years.

When we meet the book’s protagonist, Jack, he’s anxiously but joyfully coming to terms with the discovery that his wife—who shares her name with the book—is pregnant. Though they’ve been together for six years, he doggedly maintains an idealized image of her. At one point, she alludes to her stormy life before she met him, claiming, “It was like a horrible reality show.” “I don’t want to hear about it,” Jack responds, his eyes closed, wilfully blinding himself to her history. In the following panel Clowes draws the two from behind, backs turned to their separate pasts as they walk together toward a shared future.

That future is cruelly interrupted: A few pages in, Jack comes home to find Patience dead on the floor of their apartment. Despite his overwhelming grief, the police accuse him of murdering her, only to exonerate him once they actually evaluate the evidence. Seventeen years pass, the crime still unsolved, and he never stops mourning her. He refuses to even touch another woman, convinced that to do so would be to betray Patience, that there “may be some little piece of her, some cell left on my skin.” If he’s still in love, it’s because he’s never lost the unblemished image of her that he invented years before. But to get her back, he’ll have to ruin it.

Jack gains the power to undo his greatest tragedy when he steals a time machine from a sad-sack inventor. He sets a course for Patience’s youth, hoping that he can learn who might have wanted to harm her so he can take his vengeance before they take theirs. Though this device promises to help him save his beloved wife, using it means confronting the parts of her life he’s always ignored. To protect the woman he loves, he risks disrupting the very fictions that underwrote his love for her.

All time travelers suffer, and Jack is no exception, watching everything go wrong on his quest to set things right. Though he keeps telling himself that he’s just there to observe, he can’t help but intervene in the younger Patience’s misadventures. In the process, he courts what would be an even worse loss for him—that the best way to save Patience might be accidentally engineering a future in which she never makes her way to him at all.

Confronting this terrifying possibility entails negotiating a truth that we all work through, sooner or later: Everything our partners have been through brought them closer to us. Much as we might like to save them from their suffering, we know that without such pain we would never know them at all—and so we suffer too. Learning this, we’re forced to accept that there are parts of them that we can never share in, parts that define and shape them, forging them into the people we love. Similar issues play out in Leanne Shapton’s Was She Pretty, a catalog of ex-lovers that shares some of Patience’s thematic concern with heartbreak. Here, however, the lesson takes on a more sorrowful weight: Jack’s journey may be the stuff of science fiction, but it demonstrates what we all endure when we delve into our partners’ pasts. Even the most happily coupled know that there is no time machine more devastating than an attentive ear.

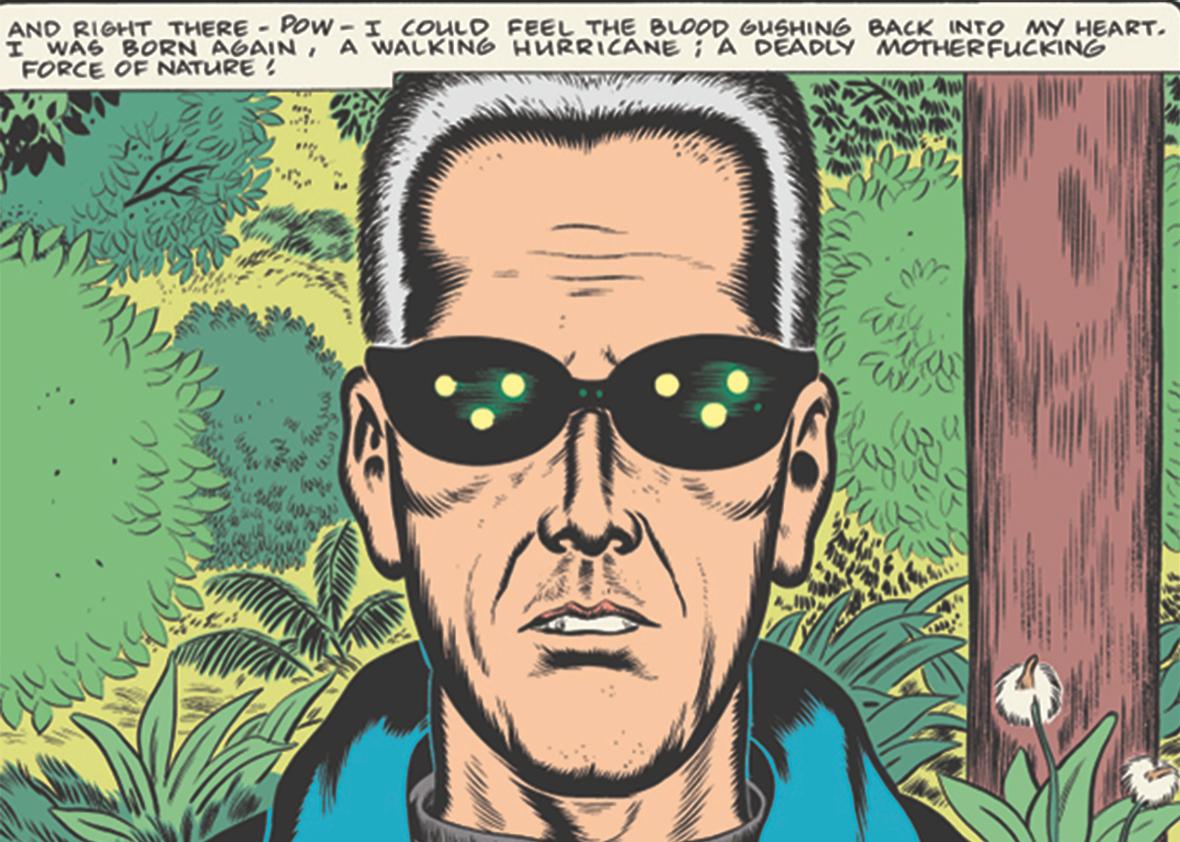

Inevitably, any reflection on coupledom is bound vibrate with anxiety, but Patience as a whole is a surprisingly calm work, probably Clowes’ most confident and clear-headed book to date. Visually, he’s often been a promiscuous stylist, varying his technique from one episode of a story to the next. Especially in later books such as Ice Haven and Wilson, those shifts have allowed Clowes to maintain a degree of emotional detachment from his narratives, turning even the most serious material into a joke. That uneasiness—which often reads as contempt—has largely vanished here. There’s still something distant about his tone, but it’s distance of a more comfortable kind. Clowes conveys that attitude with the thickly inked lines that define his characters’ features, lines that mark their individuality, even when they strive to dissolve into one another and the world around them. It’s there too in Patience’s unnerving gaze on the cover, a stirring counterpoint to her husband’s loving obliviousness.

A similar clarity of purpose is evident in Clowes’ writing. Narration—mostly from Jack’s perspective, but occasionally from Patience’s—accompanies long sections of the book. Though Clowes has always been a deft prose stylist, his best works have typically eschewed this sort of first person commentary. In those that do employ it—early short stories such as “Caricature” and “Black Nylon,” for example—the narration often drips with self-loathing, his characters giving the uncomfortable impression that they’re speaking for their author, voicing his contempt for himself. While Patience frequently exhibits that same emotion, for once Clowes himself doesn’t seem to be either its subject or its object. His new book puts ugly feelings on display, but doesn’t wallow in them.

As it approaches its conclusion, Patience suggests that breaking free from self-loathing may also mean breaking free from selfishness. Jack loves Patience to the point of madness, but everything he does for her is arguably still about him. These same themes were central to the melancholy concluding chapters of Ghost World, which suggested that love sometimes functions as a limit, holding back both self and other. Patience, however, goes further, showing that to fixate on one’s own needs is to tarry with self-annihilation: Tellingly, Jack remains a void throughout—seemingly without friends or family, he has even less of a past than Patience does at the start. In one early sequence, he tells her, “I don’t want to hang out with other people. I only like you and the baby,” referring to their still unborn child. His love for her blinds him to everything else, every other feature of his life.

Fantagraphics Books

Patience, for her own part, goes through even more, though we see less of it. She never learns, as Jack does, what her partner was before her, but she does discover what he might become after her, what he might be without her. This is her curse, and it is, we gradually realize, far more powerful than his: Etymologically, her name borrows from a Latinate root that means suffering. It’s hard to imagine a more acute emotional expression of that state than the realization that we only ever constitute a tiny fragment of our beloved’s time.

And time, ultimately, is what matters here most. Comics aren’t time machines, but they are chronological atlases, each panel a frozen instant, each page a map. Exploiting this quality of comics, Clowes dramatizes the painful work of putting together the pieces of a beloved’s history. And as he does so, his book rewards attention to its details as much as it does to the difficult, moving whole. In Patience, each assured and elegant panel reminds us that every moment matters.

—

Patience by Daniel Clowes. Fantagraphics.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.