In the opening moments of Terry Zwigoff’s 2001 film Ghost World, the camera creeps past a series of suburban windows, offering brief glimpses of the lives within. The effect is uncomfortably voyeuristic, but it’s also deeply melancholy, despite the jaunty Bollywood tune that plays in the background—here a woman stares off into space, here a man in his boxers sits at a table alone. These are lonely lives, sad lives, not the kind of experience that you want to invade. And yet you’re pulled deeper and deeper into them.

This effect is a hallmark of the work of the cartoonist Dan Clowes, whose comic of the same name provided Zwigoff with his source material. A central figure in the American independent comics movement of the last three decades, Clowes, in his comics, all but dares his readers to explore the lives of the miserable and the mean, and find unexpected moments of wisdom and vitality within them.

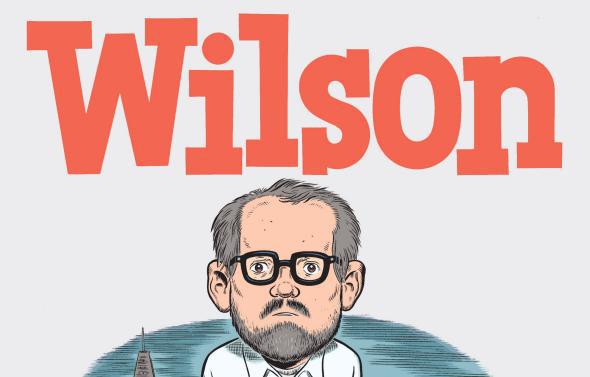

Now Fox Searchlight has started shooting Wilson, a new Clowes film adaptation, directed by Craig Johnson (The Skeleton Twins) and starring Woody Harrelson and Laura Dern. This group of collaborators represents an odd and intriguing choice for Wilson, one of Clowes’ best and most moving works. The selection of Harrelson—who has been attached to the film since May—to play the eponymous lead is especially significant, largely because the comic itself focuses almost relentlessly on its protagonist, rarely departing from his immediate perspective. Indeed, many of Clowes’ panels focus directly on Wilson’s face as he looks out, dead-eyed, toward the reader, speaking aloud to no one in particular. Balding, pudgy, and generally dowdy, Wilson is nearly charisma-free, and feels leagues from Harrelson characters like his True Detective protagonist Marty Hart.

At once needy and misanthropic, Wilson spends much of the novel reaching out to others—strangers in coffee shops, his estranged ex-wife, his dog walker—but he’s also frequently abusive and unpleasant. Despite this, his story is often quite funny, partly because every page of the book is structured like an individual gag comic strip, each of them with a sharp punch line in its final panel. With each new page, Clowes changes his art style, sometimes approaching realism and sometimes descending into stark cartoony abstraction. As NPR’s Glen Weldon noted in his review of the book, “The net effect is like reading a series of Bazooka Joe comics written by Jean-Paul Sartre.”

It’s difficult to imagine how the formal complications of Wilson will play out on screen. But with Clowes himself writing the script—as he did previously for Ghost World and the less well-liked Art School Confidential—it’s sure to remain true to the original’s pervasive tone of misery, a tone leavened by the tiniest hints of uplift. Johnson’s The Skeleton Twins, a film about suicidal twins, hits similar notes, which suggests he’s an ideal match. And whatever the medium, more of Clowes’ acerbic—and slyly caring—voice is always welcome.