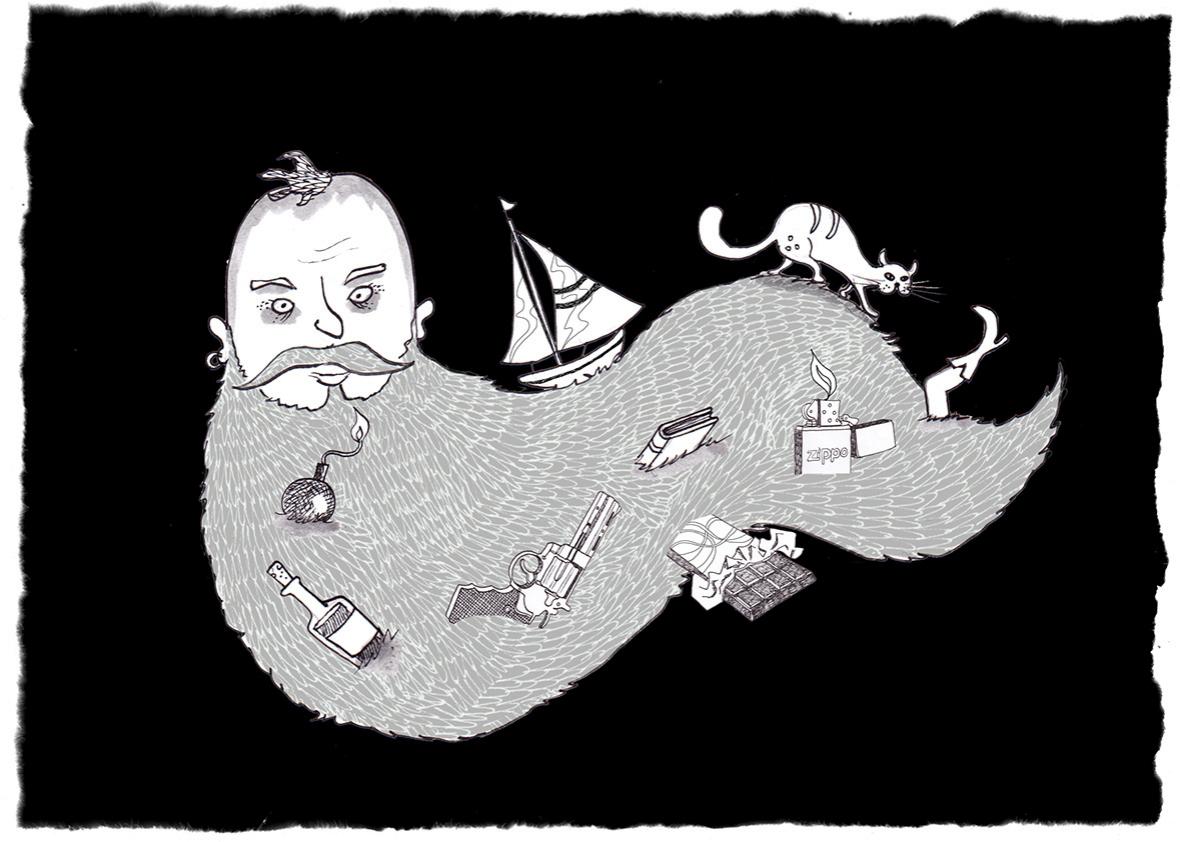

In December, when a Dallas food writer took on a pair of Brooklyn chocolatiers over the integrity of an operation they’d branded as an authentic, artisanal, hand-crafted, “bean to bar” company, he aimed just below the chin. Scott Craig argued that the thirtysomething brothers had exaggerated claims of developing innovative techniques, sourcing bespoke machinery, and working only with the most basic holistic ingredients in building their chocolate empire. And all the while, Craig added, the Mast brothers wore beards. Big, bushy, ginger beards. Sea captain beards. Civil War general beards. Hipster beards. The title of the four-part series? “Mast Brothers: What Lies Behind the Beards.”

Alongside his chocolate-based claims, Craig offered photographic evidence documenting the matching makeovers the Mast brothers underwent just as they kicked their chocolate biz into high gear. In a set of photos from 2007, the brothers sport peach fuzz on their chins, schoolboy ties around their necks, and Coronas in their hands, but by 2008, they’re styled like daguerreotype boyfriends, complete with steely gazes, sepia-tone suits, and wide, wooly beards. Michael Mast, Craig alleges, “even dyed his hair and beard red.” The bean-to-bar brothers, one commentator observed, had meticulously crafted their own personae “from bros to beards.” And people haaaaaated them for it.

Facial hair has long been associated with the fraudulent, the fake, and the fishy. “The beard, being a half-mask, should be forbidden by the police,” the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer argued in 1851. A fake mustache is, after all, a staple of the dime-store disguise. When a prisoner’s right to grow a beard reached the Supreme Court in 2014, one warden warned of weapons hitching a ride to criminals’ chins. Even after the court affirmed a statutory right to a half-inch of growth for religious reasons, Texas prisons refused to extend beard privileges to inmates with a history of escape attempts, claiming that the hair posed a danger on the outside: A clean-shaven fugitive would have to obtain a disguise to change up his look, but a bearded man just needs a shave.* In 1840, in fact, Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew and heir, Louis-Napoleon, effectively shaved his way out of a French fortress when he removed his trademark angular mustache and chin poof and, adopting the swagger of a construction worker, walked out the prison gates.

Such aspersions often take on a sexual flavor. A woman who dates a closeted gay man to help craft a hetero image is called a beard. In 1960, the razor industry exploited the beard’s untrustworthy vibe, warning women that “bearded men are often dangerous, independent to a fault, and prone to stay out all night without revealing incriminating evidence around the jawline.” Consider: After weathering a summer nanny scandal under the protection of a scraggly beard of shame, Ben Affleck recently submitted to a shave, leading tabs to speculate whether the clean shave signified a spiritual cleanse, perhaps even a coming-clean with estranged wife Jennifer Garner. And when the perma-stubbled Drake debuted a big-boy beard this year, earning high marks from a vocal contingent of female fans, some haters questioned whether the rapper had filled out naturally: Type “Drake beard” into Google and the search engine suggests you explore such concepts as “Drake beard fake” and “Drake beard transplant.” If he’s had the latter, he would join the subjects of an October New York Times trend piece about men willing to shell out tens of thousands of dollars for facial hair transplants in pursuit of a “stronger, manlier look.”

The fervor to ID a beard of deception represents the antidote to another cultural narrative: one linking beards with a certain kind of appealing, authentic masculinity. The New Yorker’s Nathan Heller coined the term “achievement beard” this year to refer to the scruff grown to mark the end of a career that requires the daily corporate shave. (David Letterman’s face is currently taking a victory lap in a midlength white number.) And after a century of association with leftist rebellion—the beards of Marx, Lenin, and Lennon—beards are now being embraced by conservatives hoping to signal a throwback to what they view as a more “natural” cultural order. See: evangelical pastor Rick Warren’s goatee; the Duck Dynasty clan’s pairing of wild beards and entrenched homophobia; and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, who has attributed his growing beard to a pact undertaken by his bow-hunting club.

“The history of men is literally written on their faces,” the historian Christopher Oldstone-Moore writes in his sweeping work of follicular anthropology, Of Beards and Men, and the “language of facial hair is built on the contrast of shaved and unshaved.” Men have been growing beards, shaving beards, or philosophizing about the meaning of beards as a strategy for achieving social dominance over rival men (and all women) for millennia. A man’s facial hair is an ambiguous stylistic feature—it registers both as a natural occurrence and a personal choice—and because shaving is now encoded as the cultural default among the Western white men who see themselves as the standard-bearers, a man who rocks a beard makes a statement. The bearded man represents “male dignity in an age of increasing gender equity,” Oldstone-Moore writes. “There is often talk of expressing one’s authentic self.”

That’s an old line. Early beard theorists charted scientific links between facial hair and the very essence of manliness. In ancient Greece, Oldstone-Moore writes, Hippocrates and his contemporaries believed in a masculine life force they called “vital heat,” an invention they leveraged to justify claims of natural male superiority in strength, reason, and beard growth. (The history of beards could also be seen as a history of men making irrational arguments to prove their superior faculties of reason.) These guys also believed that semen was stored inside the head, that it drained to the face when a man assumed a missionary sexual position, and that it bloomed, when fertilized with a generous serving of vital heat, into a beard. By 1603, Italian philosopher Marco Antonio Olmo had figured out where semen comes from, but he floated a more psychic connection between chin and crotch, calling facial hair the outward-facing manifestation of a man’s “genital spirits.” (The “Movember” movement, which encourages November mustache growth to raise awareness of prostate and testicular cancer, is a modern callback.) Centuries later, the bearded, balding Charles Darwin would again affirm the sexual potency of the beard, claiming that male facial hair emerged as an evolutionarily advantageous ornament for attracting women. Freudians agreed: Beards were the dicks of the face.

But they were also the windows to the soul. Though Charlemagne was a mustache guy, he was often depicted in art with a curled white beard, even contemporaneously. The artistic license, Oldstone-Moore writes, was made with an effort at telling “the story of his soul” rather than reflecting his physical reality. (Centuries later, the coining of “soul patch” would winkingly recall the association.) Other creative artistic depictions of facial hair reflected changes in the Zeitgeist: Jesus Christ was first depicted as a smooth-cheeked cherub in the style of an ancient Greek hero or god, and only sprouted his iconic beard centuries later when religious leaders called up a scruffy Son of God to emphasize the primacy of gender roles, even in the afterlife. Members of some religious sects even shaved their faces in the hopes of focusing their efforts on cultivating what they called “the inner beard.” The man who stroked his beard in thought was perceived as accessing his very essence.

Photo by Matthew J Cline

Beard theory had political uses as well. As Oldstone-Moore notes, “philosophers were history’s first pro-beard lobby,” and they fought off the influence of clean-shaven clergy or feminist women by crafting theories that hinged on their hairlines. Christopher Columbus’ contemporaries viewed facial hair as primitive and uncivilized until the scraggly sailors caught sight of the smooth-faced denizens of the “New World,” and what do you know? All of a sudden, white guys were heralding beards as a sign of sophistication. And the 1862 pro-beard tract Apology for the Beard, written just after the dawn of the American women’s rights movement, posited that facial hair protected the man’s mouth and throat in order to grease his higher purpose: “It is the man’s duty to teach with his voice,” it said. “It is the woman’s to ‘learn in silence.’ ”

The popularity of the beard ebbs and flows at the pace of social change, but at certain points in history, laws or harassment campaigns have accelerated the cycle. Peter the Great, eager to bring Russian culture in line with the fashions of modern Renaissance Europe, enacted a tax on countrymen who refused to shave. In the early 20th century, as the beard declined in Europe and the corporate shave ascended, a sophomoric scavenger hunt swept Britain: Whenever a bearded man was spotted, players competed to be the first to yell “beaver!,” racking up points for every scruff they claimed. The new game is to point and yell “hipster!”

Or “poseur.” The Mast Brothers controversy recalls the 2013 beard-shaming of the Duck Dynasty men: Styled as redneck sporting magnates for reality TV in camo bandanas and ZZ Top beards, old photos splashed across the Web reveal a past presentation as clean-shaven squares in khaki shorts and frosted tips. These fair-weather beards bother people because they attempt to leverage a symbol of masculine authenticity at an auspicious moment—the beards grow just as the foodies take notice or the cameras start rolling. These incidents raise the specter of the possibility that beneath their facial hair, there is no essential “inner beard”—that the difference between men and women is a distinction of style, not substance. Recirculating photographs of the men in smoother times acts as a kind of digital debearding.

In an interview with the Associated Press last month, Rick Mast denied the symbolic resonance of his chin hairs. “Before I had a beard, I didn’t have a beard,” he sniffed. “I know, it’s a big scandal.” Nice try. Rick Mast is a guy who has praised his chocolate’s “fiercely independent, almost Emersonian spirit” and suggested nibbling it while reading Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. (Whitman staked his own position in “Song of Myself”: “Washes and razors for foofoos—for me freckles and a bristling beard.”) Mast meticulously cuts his candy wrappers to the “thickness of an old butcher paper” and prints them with a reclaimed antique press. He transports his cocoa beans from Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic, to Red Hook, Brooklyn, on a sailboat that carries not just cargo but “the whole story” of the company. He’s claimed that his $10 chocolate “represents more than just a candy bar: It represents a new way of hand-crafting food,” or else “an old way an old mentality that’s now new.” When Rick Mast grows a beard, it has to mean something. If a beard is just a beard, then maybe a candy bar is just a candy bar.

—

Of Beards and Men by Christopher Oldstone-Moore. University of Chicago Press.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

*Correction, Jan. 4, 2016: This article originally misstated that the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of inmate Gregory Holt was made on constitutional grounds. The case dealt with the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, a federal statute, not the Constitution.