“All the new thinking is about loss,” Robert Hass wrote in his classic 1979 poem Meditation at Lagunitas. “In this it resembles all the old thinking.” Most art by its nature has an elegiac element, in the way it mimics memory, and in its awareness that to try to represent the world is inevitably to miss some of it too, to feel truth slipping out of grasp, running between the fingers and evaporating.

As the prolific songwriter who performs (whether solo or with partners) as the Mountain Goats, John Darnielle battles back against that slippage with a host of strategies I might categorize as surprise attacks. Many of his songs are short and fast-paced, but most of all they tend to focus on the flash of a moment when something changes or a revelation falls into place; they shine a spotlight on that ineffable sensation and then short out before it has a chance to fade. So, even if they are, like all the new and old thinking, about loss, it is most often in the mode of trauma—of the sudden blow that renders the lost object or the lost self unreachable, and fixes attention on the shape of its absence.

Loss is a human constant, but for each person it occurs each time as if it were the first. When your house catches fire, it does not matter how many buildings have burned before. That is what Mountain Goats songs are mainly about, whether tender or noisy or ridiculous.

When critics and journalists discuss Darnielle’s new, first full-length novel, Wolf in White Van, which was just nominated for a National Book Award, they often point out the storytelling aspect of his songwriting. But Mountain Goats songs are as much incantation as narrative—they imply the advent of the trauma with declarations and appeals to dead gods, which deny it or try (futilely) to ward it off. “When I receive the blessing I’ve got coming,” Darnielle crows in 2004’s “Quito,” “I’m going to raise an ice-cold glass of water/ and toast the living and the dead/ who’ve gone before me, and my head/ will throb like an old wound reopening.” Images of black ritual, fantasy, and escape stake an outline around unspeakable realities.

Wolf in White Van is likewise quite explicitly about living with trauma, or refusing to, and the transformative powers of all those choices. But with 200 pages rather than three minutes to fill, Darnielle is led to explore trauma’s consequences, day to day and over time, far more finely. As a result the book is not the kind of rallying cry or dark comfort that Mountain Goats fans are used to, but a complex meditation—partially about the potential costs of those very cries and comforts. Like Darnielle’s songwriting, the prose is often cryptic and then stunningly clear, microscopically specific and then audaciously grand. The words soothe for sentences at a time, then strike with blunt force:

In Chapter 7: “Normal adult shopping is something I will never actually do, because it’s no more possible for me to go shopping like normal adults do than it is for a man with no legs to wake up one day and walk. I can’t miss shopping like you’d miss things you once had. I miss it in a different way. I miss it like you would miss a train.”

In Chapter 10: “There was a small, strange moment during which I had the feeling that someone was filming me. … It is a terrible thing to feel trapped within a movie whose plot twists are senseless. This is why people cry at the movies: because everybody’s doomed.”

(Darnielle’s own urgent spoken performance of the book, by the way, is not to be missed.)

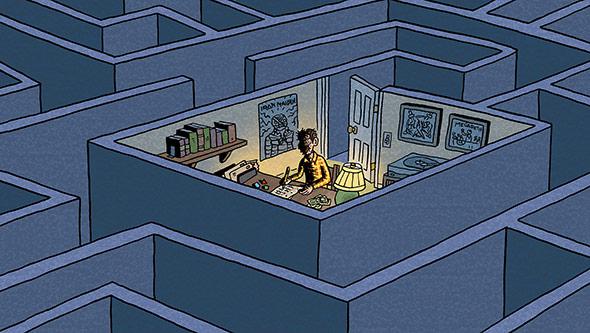

The reader learns early on that the narrator, Sean Phillips, was horribly disfigured in an unspecified “accident” as a teenager, a decade or more ago. At first that vagueness is frustrating, making the first couple of chapters a bit laborious to read. Then it becomes clear that the novel is going to track its way back toward that event, seeking to explain it—or perhaps more accurately to fail to do so, in great detail, as if penetrating ever deeper into a maze that has no center.

This is also the nature of the game Sean has invented, a retro role-playing adventure called Trace Italian. It too enters the story as a kind of oneiric presence that only gradually reveals itself as an actual thing; indeed, this game, in which players participate by snail mail, paying a monthly fee to post their next move to Sean’s P.O. box, is Sean’s prime source of income. This makes it both more banal and more amazing, until we discover that it’s also had unintended real-world effects for at least two of its adolescent participants. Whether Sean is legally or morally culpable for what’s happened is a central issue, leading to the question of his own fate, and who, if anyone, is to blame.

Adolescents in crisis are a touchstone of Darnielle’s empathic imagination. His only previous published long prose work—Master of Reality, an essay-cum-novella on Black Sabbath in the 33⅓ series of books about albums—was about a teen boy confined to an institution pleading with the doctors to give his heavy-metal tapes back. Many of his songs (e.g. “The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Denton”) portray similar characters. Before he became a full-time musician, Darnielle gained up-close experience with such troubled kids as a psychiatric nurse. (The new novel is great on the maddening tedium of hospitals, treatment, and recovery.) Later, fans learned that he’d been one of those kids himself, physically abused by his stepfather, as chronicled on his album The Sunset Tree, and later caught up in hard-drug use, as evoked on the album We Shall All Be Healed.

Really, though, anyone whose days are spent making and thinking about popular music is apt to dwell on adolescence. Studies show the music we listen to in that phase of life stays with us—indeed for many people it is the only period of intense music listening in their lives, bound up with the raw extracting process of becoming an adult, some particular adult, whether under duress or in relative comfort. And when you are a performer with an intense following of teens and young adults, as the California-born, North Carolina–based Darnielle has become as he’s progressed from home taper in the 1990s to touring indie star today, you have your fans to reinforce for you that those ordeals continue always and everywhere.

Sean has the same experience with his letter-writing gamers, who scrawl bits of their lives into the margins of their moves, sometimes for company and sometimes, as with one boy, involuntarily, “the parts he hadn’t been able to stop himself from mentioning, the pieces of himself that flew from him naturally like sparks from a torch.” Sean also learns, in spades, due to the grotesqueness of his face, what it’s like to be conspicuous and stared at—which Darnielle/Sean directly compares at one point to being famous. Both the Trace Italian storyline and the emerging details of how Sean’s injury might link to his own teen immersion in fan culture (particularly of Conan the Barbarian novels and comics) raise the problem of an artist’s responsibility for his fans’ potential misinterpretations and wild misuses of the work.

The novel’s title refers to the kind of controversy that usually raises that problem—in this case, supposed satanic messages concealed on rock records. One song by 1970s Christian rocker Larry Norman was accused of backward-masking the phrase, “Wolf in white van,” which— as Darnielle has Sean note— seems like a pretty obscure thought for the devil to go to such lengths to deliver. The idea of playing songs in reverse parallels the structure of Darnielle’s novel, but it also reminds us how metal and goth bands, Dungeons & Dragons, horror movies, and other works of art have been indicted for their supposed roles in teen suicides, murders, and even mass killings.

Courtesy of Lalitree Darnielle

In everyday life, Darnielle would be the first to decry that kind of crude heuristic and to say that these entertainments, no matter how apparently nihilistic or aggressive, are actually lifelines that give people a place to put their pain, and a sense that they are not alone with it. (“No child has ever been harmed by music,” he told an interviewer once.) Yet with a novel’s ability to play every side of a drama, without having to endorse a final answer, in Wolf in White Van Darnielle is able to dig into an artist’s forbidden fears and doubts, even delusions of potency: What if the incantation does not always ward off evil but sometimes, unintentionally, summons it? What if it gives the hidden beast (the wolf?) meat to feed on? What if that happens and the artist never even hears about it?

In enjoying morbid art, it is necessary that danger feel present. It’s the shimmer of the blurred boundary that’s the lure, despite liberal platitudes that the free play of fantasy is wholesomely inconsequential. After all it’s liberal platitudes, the dry coercion of common sense, that those thrillingly unhealthy fantasies are meant to counter. But as Darnielle sings in his unrecorded song “You Were Cool,” a fan favorite: “It’s good to be young, but let’s not kid ourselves/ It’s better to come through those years … with our hearts still beating/ Having stared down demons and come back breathing.”

Not everyone does. The mutilated Sean in Wolf in White Van is a reminder, a totem of that fact: still breathing, but never easily. (“The people ahead of me in line,” Sean tells us, “always get nervous when they hear me breathing, which has a wet sound I can’t help.”) Yet he is not sure he wants to undo or too much ameliorate his condition, even superficially. There’s a truth he doesn’t want to forget, or one it’s important he not remember. He’s not sure he doesn’t lead a normal life, and by the book’s end, neither are we. Don’t you hear the unending buzzing of your trauma in your ears and feel your sutures loosen under moisture and heat? Don’t you sense the way people avert their gazes while you long for them to meet your eyes? What’s the next turn in your quest? Whatever you decide, don’t get confused between what you do out in the world and the moves you are supposed to make only in your mind. All the new losses are about thinking; in this, they resemble all the old losses.

—

Wolf in White Van by John Darnielle. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.