In recent years, the Supreme Court has grown increasingly paranoid about religious discrimination. The Republican-appointed justices see “animosity to religion” around every corner (unless it emanates from Donald Trump). They have been keen to shield people of faith—specifically, conservative Christians—from the faintest whiff of offense. And they have been eager to grant exemptions to religious plaintiffs who insist that complying with the law would violate their beliefs. At no point in any of the court’s recent religious liberty cases did these justices even raise the possibility that these plaintiffs had feigned or exaggerated their beliefs.

Until Tuesday. During arguments in Ramirez v. Collier, several conservative justices expressed serious skepticism toward the sincerity of a religious plaintiff’s faith. The difference between Ramirez and every past case? John Henry Ramirez is on death row, and his demand for a Baptist pastor in the death chamber has delayed his execution date. It turns out that these justices do think that courts can assess the authenticity of religious objections … but only when the objector is about to be killed by the state.

The facts of Ramirez are heavily disputed, but the outline goes like this: In 2008, a Texas jury sentenced Ramirez to death for murder. Behind bars, he has received counseling from Dana Moore, a pastor at the Second Baptist Church in Corpus Christi. Moore routinely drives more than 300 miles to minister to Ramirez behind a plexiglass window. Ramirez, a devout Baptist, would like Moore to accompany him in the execution chamber when he is put to death by lethal injection. Specifically, he wants permission for his pastor to pray by his side and lay hands on him when his heart stops.

Texas refuses to grant this accommodation. The state’s lawyers alleged that the active presence of the pastor would imperil the “safety” of all involved. (They did not address the irony of fretting about “safety” during a procedure designed to kill someone.) So Moore filed a lawsuit alleging an infringement of his constitutional right to free exercise as well as a violation of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000. This federal law, known as RLUIPA, prohibits the government from imposing a “substantial burden” on the religious exercise of incarcerated people unless it is “the least restrictive means” of furthering a “compelling governmental interest.”

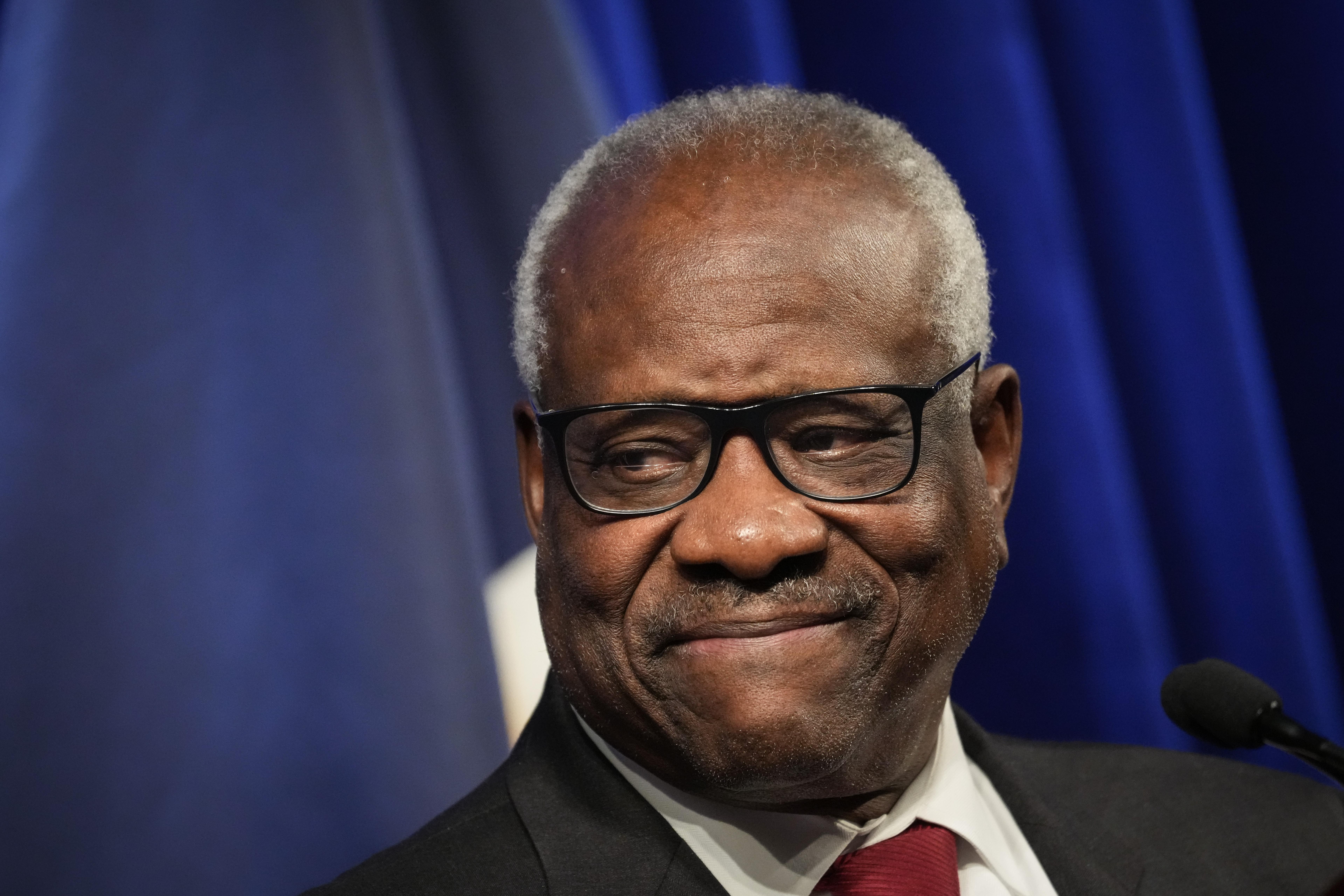

The justices have grappled with the issue of religious liberty for those condemned to death for several years in a series of contradictory shadow docket orders that failed to establish a clear rule. They seemed to take up Ramirez in order to lay down a standard that would stem the tide of last-minute requests to stay an execution on religious liberty grounds. As soon as arguments began, however, it became clear that Justices Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, and Sam Alito had a different goal in mind: to undercut Ramirez’s claim altogether by proving that he feigned a religious objection to delay his execution. Their ostensible evidence is the fact that Ramirez raised multiple objections to different restrictions each time the state scheduled his execution. Texas encouraged this narrative in its brief. But the state’s claims are objectively bogus: The full record reveals that the state itself repeatedly changed the rules to limit the pastor’s access to the death chamber and concealed these shifting guidelines from Ramirez until just before his execution.

Ignoring these facts, Thomas seemed to buy into Texas’ highly suspect version of events. He asked Seth Kretzer, Ramirez’s attorney: “If we think that Mr. Ramirez has changed his request a number of times and has filed last-minute complaints, and if we assume that that’s some indication of gaming the system, what should we do with that with respect to assessing the sincerity of his beliefs?”

Kretzer pointed Thomas toward Ramirez’s multiple handwritten pleas “repeatedly requesting the same thing,” but Thomas sounded doubtful. “Can one’s repeated filing of complaints, particularly at the last minute, not only be seen as evidence of gaming of the system but also of the sincerity of religious beliefs?” he asked. Kretzer responded: “I can only speak as Mr. Ramirez’s attorney. I do not play games. There’s no dilatory tactics in this case.”

It wasn’t good enough for Alito, who groused to Kretzer that “what you have said so far suggests to me that we can look forward to an unending stream of variations.” As if to tease out the many ways people could “game the system” to delay their executions, Alito asked: “What’s going to happen when the next prisoner says that I have a religious belief that [my faith adviser] should touch my knee? He should hold my hand? He should put his hand over my heart? He should be able to put his hand on my head? We’re going to have to go through the whole human anatomy with a series of cases.”

Kavanaugh picked up on Thomas’ thread, too. “People are moving the goal posts on their claims in order to delay executions,” he lectured Kretzer. “At least, that’s the state’s concern.” Later, Kavanaugh added: “This is a potential huge area of future litigation across a lot of areas—sincerity of religious claims. How do we question those? Some things people have talked about are the incentives someone might have to be insincere, behavioral inconsistencies … the religious tradition of the practice. What do we look at to check sincerity? Because that’s a very awkward thing for a judge to do, to say: ’I want to look into the sincerity of your claim.’ But our case law says we must do that.”

Which case law, exactly, is Kavanaugh talking about? Because in recent history, the Supreme Court has emphatically refused to apply the slightest scrutiny to religious objections. When Hobby Lobby claimed that allowing their employees to access IUDs and morning-after pills through their health insurance violated the company’s religious beliefs, SCOTUS did not question its sincerity. The conservative majority even adopted Hobby Lobby’s position that these forms of contraception cause abortions, which is empirically false. When a pharmacy asserted that selling Plan B violated its religious beliefs based on the same misunderstanding, the conservative justices didn’t blink. When religious employers said that filling out a form to exempt them from the contraceptive mandate would undermine their faith, SCOTUS nodded along. When a baker declared that providing a wedding cake to a same-sex couple infringed on his faith, these justices did not ask why, exactly, the sale of baked goods contravened the tenets of his creed. When a Catholic charity claimed that simply certifying LGBTQ people as fit foster parents clashed with the church’s principles, not a single justice probed its sincerity. And when health care workers protested the COVID vaccine on religious grounds, three conservative justices avidly embraced the validity of their objections.

The hypocrisy goes deeper. In Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, the Supreme Court held that a state official violated the free exercise clause by uttering a banal comment criticizing the use of religion to justify discrimination. If an offhand criticism of someone’s faith can violate the Constitution, surely a full-on investigation of someone’s religious beliefs can, too. Indeed, by the standard laid down in Masterpiece Cakeshop, Thomas and Kavanaugh’s statements on Tuesday might be unconstitutional “animus” toward Ramirez’s faith. The same is true of Texas’ efforts to refute Ramirez’s beliefs. To use the language of Masterpiece Cakeshop, the justices and the state’s lawyers expressed “impermissible hostility” toward Ramirez’s religion-based objections, failing to pay them the “neutral and respectful consideration” commanded by the First Amendment. They characterized these objections as “insubstantial and even insincere,” betraying their “solemn responsibility of fair and neutral enforcement” of the law.

Of course, Supreme Court justices don’t play by the same rules that they lay down for the rest of the country. Thomas, Kavanaugh, and Alito probably see no inconsistency in their approach to religion: They view death row inmates as inherently untrustworthy, desperate to extend their doomed lives through endless litigation. They aren’t the right kind of religious objectors, so they don’t receive the deference afforded to, say, a Christian arts and crafts store.

What’s unclear is whether the other conservative justices will go along with this hypocrisy. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked probing questions that didn’t tip their hands, while Justice Neil Gorsuch said nothing at all. The liberals have consistently supported religious liberty in the death chamber, and Barrett has sided with them in the past. Whether there are five votes for a strong rule protecting Ramirez—and all those who will come after him—remains unclear. What’s certain after Tuesday is that some justices’ commitment to religious freedom ends the moment that religion might briefly halt the machinery of death.