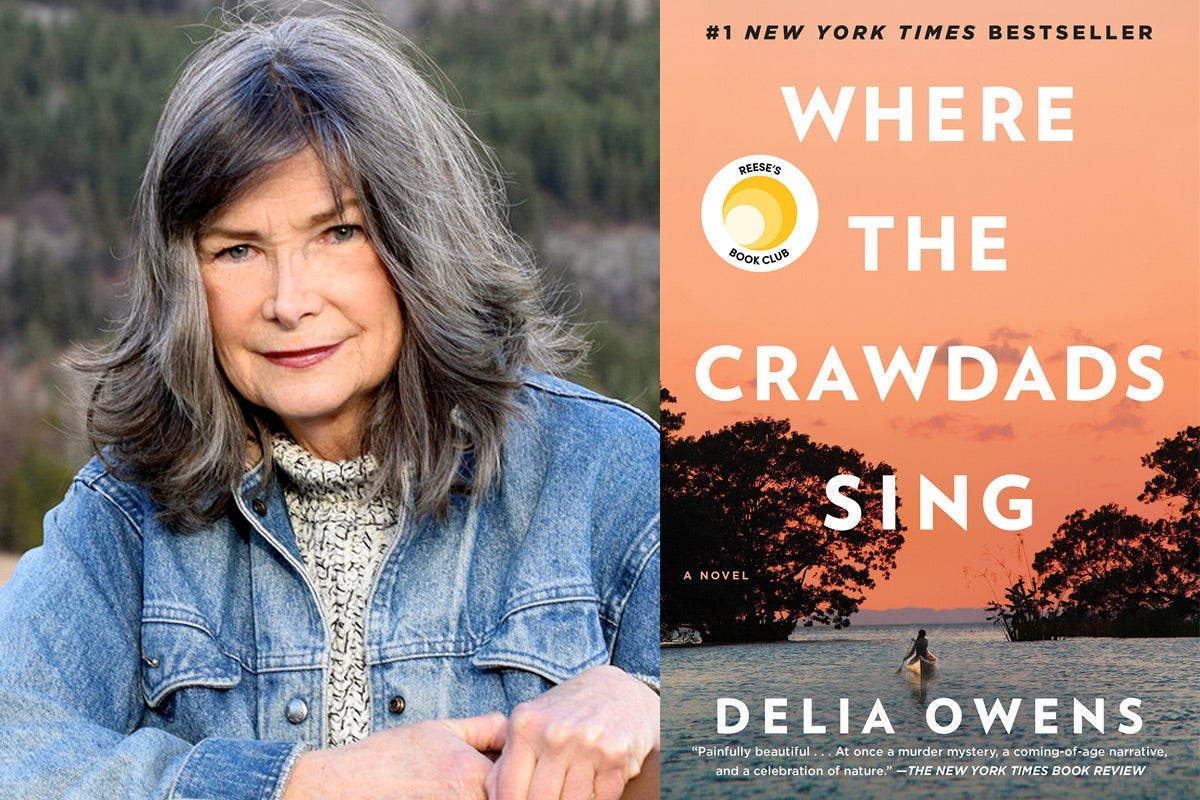

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens is the sort of book that you’ve either never heard of or have already read for your book club. The bestselling hardcover title of 2019, Crawdads has sold more than 1 million copies—jaw-dropping for any first novel, much less one by an author who just turned 70, living on a remote homestead in northern Idaho. Publishers Weekly has called its success the “feel-good publishing story of the year.” (Spoilers for the novel follow throughout this piece.) If you’re one of the people who’ve read the book, you probably know a little of Owens’ romantic backstory, like the huge boost her debut got when Reese Witherspoon, the Oprah of our time, selected it for her book club. Or the fact that while Crawdads is Owens’ first novel, it’s not her first book. And then there’s the 22 years she spent in Africa with her husband, Mark, living close to the land and working in wildlife conservation. Delia and Mark wrote about those experiences in three memoirs. But what most of Crawdads’ fans don’t know is that Delia and Mark Owens have been advised never to return to one of the African nations where they once lived and worked, Zambia, because they are wanted for questioning in a murder that took place there decades ago. That murder, whose victim remains unidentified, was filmed and broadcast on national television in the U.S.

To be clear, Delia Owens herself is not suspected of involvement in the murder of a poacher filmed by an ABC camera crew in 1995, while the news program Turning Point was producing a segment on the Owenses’ conservation work in Zambia. But her stepson, Christopher, and her husband have been implicated by some witnesses. This murky incident from Delia’s past is hardly a secret. In fact, in 2010 it was the subject of “The Hunted,” an 18,000-word story written by Jeffrey Goldberg and published in the New Yorker. You can find a link to that story, along with a one-line reference to a “controversial killing of a poacher in Zambia,” in Owens’ Wikipedia entry. However, the Wikipedia entry for Owens comes as only the fourth result when you Google her name, and a lazy or unseasoned internet user might stop reading after browsing the official bios that outrank it. Apparently many such users are members of the press. In numerous interviews, Owens giggles about how her publishers “keep sending me champagne” or recounts how she was inspired by her observations of animals that “live in very strong female social groups.” (No such group appears in Where the Crawdads Sing.) But when it comes to the remarkable fact that, in the company of a charismatic but volcanic man, she apparently lived through a modern-day version of Heart of Darkness? Not a peep.

Goldberg—who spent months researching “The Hunted,” traveling to South Africa, Idaho, and Maine in addition to making three trips to the Luangwa area in Zambia, and interviewing over 100 sources—is bemused by how effectively Owens and her publisher have managed to overshadow perhaps the most fascinating, if troubling, episode in her life. “A number of people started emailing me about this book,” he told me in an email, “readers who made the connection between the Delia Owens of Crawdads and the Delia Owens of the New Yorker investigation. So I got a copy of Crawdads and I have to say I found it strange and uncomfortable to be reading the story of a Southern loner, a noble naturalist, who gets away with what is described as a righteously motivated murder in the remote wild.”

Several sources Goldberg spoke with, including the cameraman who filmed the shooting of the poacher, have stated that Christopher Owens—Mark Owens’ son and Delia Owens’ stepson—was the first member of a scouting party to shoot the man. (Two other scouts followed suit.) Others have claimed that Mark Owens covered up the killing by carrying the body, which was never recovered, up in his helicopter and dropping it in a lake. Whoever pulled the trigger that day, what seems indisputable from “The Hunted” is that, over the course of years, Mark Owens, in his zeal to save endangered elephants and other wildlife, became carried away by his own power, turning into a modern-day version of Joseph Conrad’s Mr. Kurtz—and that while Delia Owens objected, at times, to what was happening, she was either unable or unwilling to stop him or quit him. And despite being set in a different place and time, her bestselling novel contains striking echoes of those volatile years in the wilderness.

Mark and Delia Owens first arrived in Zambia in 1986 after getting kicked out of Botswana, where they had made themselves unwelcome by criticizing the government’s conservation policies. The young couple sought out a preserve in Zambia’s North Luangwa wilderness, an area whose indigenous inhabitants had been expelled by the nation’s former British rulers. They were drawn to the region’s isolation and then dismayed to discover that poachers were devastating the local elephant population. Some of the animals were killed by people who had lived in the surrounding area for generations and whose ancestors had long hunted its large mammals for meat, but the greatest threat came from poachers feeding a booming international ivory market.

These well-armed poachers overmatched the ragtag band of park service scouts charged with protecting the elephants. The Owenses raised money from European and American donors to better pay and equip the scouts; in exchange, they were named “honorary game rangers” by the Zambian government. According to many sources Goldberg spoke with in Zambia, Mark Owens became the de facto commander of the scouts, harrying poaching parties with firecrackers shot from a Cessna and later, from a helicopter, menacing them with a machine gun. Under his command, scouts raided villages and roughed up residents in search of suspects and poached loot. In one (highly contested) letter, Mark Owens informed a safari leader that his scouts had killed two poachers and “are just getting warmed up.” (Mark and Delia Owens deny most of these claims, alleging various conspiracies against them by those who resented their success and fame or who had a corrupt financial interest in the poaching trade.) “They thought they were kings,” the recipient of this letter said of the Owenses. “He made himself the law, and his law was that he could do anything he wanted.”

Delia Owens sometimes objected to the risks her husband took in combating the poachers, and in their co-authored 1992 memoir, The Eye of the Elephant, she describes at one point separating from him and building her own camp four miles away. Eventually, the couple reconciled. After the ABC story aired and Zambian authorities became alarmed at the idea of a foreign national overseeing a shoot-to-kill policy in one of their preserves, the Owenses traveled to the U.S. for a visit and never returned. According to Goldberg, “The American Embassy warned the Owenses not to enter Zambia until the controversy was resolved,” but as of 2010, the case was still open. “There’s no statute of limitations on murder,” an investigator told Goldberg. Mark Owens confirmed to me through his attorney that there have been no further developments in the case and noted that no charges were ever filed. His attorney also confirmed that the pair never returned to Zambia. I was unable to reach Christopher Owens.

The Owenses then moved to a remote area of land in Boundary County, Idaho. The couple “eventually divorced but remain friendly and live on the same acreage,” according to an edit to Delia Owens’ Wikipedia entry made on June 10 of this year. (In the acknowledgements at the end of Where the Crawdads Sing, Delia thanks Mark Owens for being one of the novel’s early readers.) A Wikipedia editor later deleted the passage, noting to the person who had altered Delia Owens’ entry and nothing else on the entire site, “Sorry if you have personal knowledge but articles must be based on verifiable sources.” In an interview with Amazon, Delia describes Mark as her “former husband,” and posts to her Instagram account suggest that she recently moved to North Carolina.

On first impression Where the Crawdads Sing, with its mid–20th-century Southern setting, suggests that Delia Owens has gotten over the traumas of her African years and the losses brought on by the exposure of her husband’s behavior in Zambia. Her novel is the story of a white girl who essentially raises herself in the swamps of North Carolina in the 1950s and early 1960s. Abandoned by her family and mocked by her classmates during the single day she agrees to attend public school, Kya Clark prefers to commune alone with nature, collecting specimens and producing exquisite drawings of the swamp’s flora and fauna. (Eventually, these are published in a series of successful books.) Kya’s story alternates with chapters set in 1969, in which Chase Andrews, a womanizing former quarterback, is found dead under an abandoned fire tower and police investigate the death as a possible murder.* Kya, stigmatized as “the Marsh Girl” by the townsfolk, is charged with the crime, and the last quarter of the novel depicts her trial.

“Almost every part of the book has some deeper meaning,” Owens said in her interview with Amazon. “There’s a lot of symbolism in this book.” To anyone who has read “The Hunted,” those lines are tantalizing, even if Owens doesn’t mean them to be. Having her heroine stand accused of murder echoes the Owens’ Zambian experience and the subsequent ordeal of becoming the subject of a 18,000-word exposé in a prominent magazine. Even more eyebrow-raising is the plot twist in the novel’s final pages: It turns out Kya did, after all, murder Chase.

Kya’s similarities to Delia Owens, who grew up in Georgia, are manifest. Both are lonely, yet prefer the company of animals to people; the Owenses’ memoirs recount one long search for life outside the human fold. “Here’s where civilization ends,” Mark once said admiringly of North Luangwa, Goldberg reports. Kya is depicted as a misunderstood victim, cast out of society by the small-minded prejudices of her neighbors. In his closing statements, her defense attorney exhorts the jury and the town itself to examine its conscience: “We labeled and rejected her because we thought she was different. But, ladies and gentlemen, did we exclude Miss Clark because she was different, or was she different because we excluded her?”

In every respect, Kya is wronged by those around her. Her father abuses the rest of the family, forcing her mother and siblings to leave. Her first love, a fellow marsh habitué who sweetly teaches her to read and write, does not return for her as promised once he leaves for college. White-gloved mothers pull their children away from her on the streets, calling her “dirty.” Chase seduces her with talk of marriage and children, but instead chooses a more socially acceptable bride. Later, he tries to rape her.

In the absence of any better models, Kya looks to the animals around her and reads scientific articles for insights into human behavior:

Some behaviors that seem harsh to us now ensured the survival of early man in whatever swamp he was in at the time. Without them, we wouldn’t be here. We still store those instincts in our genes, and they express themselves when certain circumstances prevail. Some parts of us will always be what we were, what we had to be to survive—way back yonder.

Apart from the novel’s final and highly implausible twist, Kya is depicted as a lovely, gentle, naϊve child of nature, devoid of any negative traits besides an unwillingness to give her first love, Tate, a second chance once he finally realizes that he can’t live without her. When Tate comes to visit Kya in her marsh cabin to plead his case, she appears as an angelic vision, “in a long, white skirt and pale blue sweater—the colors of wings.” Yet despite exhibiting no aggressive, atavistic impulses herself, Kya more than once contemplates the truth that “ancient genes for survival still persist in some undesirable forms among the twists and turns of man’s genetic code.” This idea—that, in extremis, a primitive drive for “survival” will trigger “harsh” and “undesirable” actions—resembles a moment in the ABC segment on the Owenses, in which Meredith Vieira (then a reporter for the program) describes the shooting of the poacher as the result of what “Mark Owens calls a ‘hardening of the human spirit,’ the ultimate price he has paid to work here.” Owens himself then remarks, “It’s a very dirty game. It’s a measure of the desperation of the situation, I think.”

Owens’ Kya is an impossible personality built on a moral conundrum: Her virtue arises from her purity—that is, her remove from the contaminating influences of “civilization,” with its false values, cruelty, and lies. Nature and animals, by contrast, are the locus of truth and spiritual sustenance. Nature also acknowledges Kya as its chosen daughter. When she is in custody during her trial, the jailhouse cat recognizes her quality and visits her cell at night. But “nature,” it seems, is also the excuse for Kya’s crime, which is a major one, a measure of the desperation of her situation, so to speak. And after all, isn’t Chase, like that nameless poacher, a bad man, who got his just deserts even if his killing technically violates the law of the land? Although Kya is in fact guilty, the book frames her trial as unfair, the targeting of a mistreated outsider by a community incapable of justice. And yet, she is acquitted, getting away with her crime.

Fiction writers often don’t realize how much of their own unconscious bubbles up in their work, but at times Owens seems to be deliberately calling back to her Zambian years. The jailhouse cat in Where the Crawdads Sing has the same name—Sunday Justice—as an African man who once worked for the Owenses as a cook. In The Eye of the Elephant, Delia describes Justice speaking with a childlike wonder about the Owenses’ airplane. “I myself always wanted to talk to someone who has flown up in the sky with a plane,” he said, according to Delia. “I myself always wanted to know, Madam, if you fly at night, do you go close to the stars?” When Goldberg tracked down Justice and asked him about this story, the man laughed. He had flown on planes many times as both an adult and a child before meeting Delia Owens. He later worked for the Zambian Air Force.

This example of what Goldberg tactfully calls the Owenses’ “archaic ideas about Africans” has its parallel in Where the Crawdads Sing, too. A black character, a kindly man called Jumpin’ who runs a gas station and general store for swamp boat operators, is among the very few people in the community to befriend Kya. She encounters Jumpin’ a few days after being sexually assaulted by Chase, her face still visibly bruised. “Was it Mr. Chase done this to ya?” he asks. “Ya know ya can tell me. In fact, we gwine stand right here tills ya tell me.” When Kya begs Jumpin’ not to report the assault to the sheriff, he protests that “sump’m gotta be done. He cain’t go an’ do a thing like that, and then just go on boatin’ ’round in that fancy boat a’ his.”

Even setting aside the Gone with the Wind–style dialect here (Owens is 70, after all), the scene betrays a profound racial and historical ignorance. The idea that any black man living in the rural South during the early ’60s would seriously consider reporting to local law enforcement the attempted rape of a white woman by the son of a prominent white family is ludicrous. He would have had ample knowledge of men like Chase getting away with even worse. One of the Owenses’ critics in Goldberg’s article touched on this obliviousness when he characterized the couple’s attitude toward Africa as “Nice continent. Pity about the Africans.”

Press coverage of Delia Owens since the runaway success of Where the Crawdads Sing has focused on her tomboy girlhood, her passion for helping African wildlife, and the pristine isolation of her Idaho home, portraying her as nearly as unspoiled as her heroine. But Owens’ past is far more dark and troubling than that—and also a much more interesting story than Crawdads’ tale of a persecuted, saintly misfit finding solace and transcendence in nature. Owens’ own story appears to be one of love and righteousness run amok, of the seductive properties of power and violence, of what it feels like to watch your husband become someone your neighbors have cause to fear. The Owenses have spent much of their lives trying to get as far away from humanity as they can, but theirs is an impossible quest: Like all of us, they bring humanity and its failings with them wherever they go.

Correction: This story originally misstated the year in which some of the action in Where the Crawdads Sing takes place. It is 1969, not 1965.