Is there a German compound word for desperately wanting something to end while knowing that the moment it does, you’ll wish for it back? This is the scrambled state to which 2016 has reduced many Americans: It may be one of the worst years on record, but it’s also starting to look like the twilight of a charmed era for women, minorities, and progressive principles.

Of the many ways that American life may, in retrospect, have reached its apex in these miserable 12 months, one humble but crucial item is access to birth control, which has never been more readily available in this country than it is right now. Before the Affordable Care Act, which requires most insurers to cover contraceptives with no copays, women devoted an average of 30 to 44 percent of their annual health care spending to keeping themselves on birth control. Since the law went into effect in 2012, it has helped an estimated 55 million women save billions of dollars, collectively. Just as important, the mandate has made it possible for women to choose their birth control based on their needs—do they want an oral contraceptive they can discontinue anytime or an intrauterine device they can forget about for a decade?—without having to worry about the barrier of cost.

Little did we know it, but we may have been living in the golden age of birth control. When 2016 began, the Obama administration was busy protecting a right to free contraceptives for women who work at religious nonprofits. As 2016 draws to a close, all women who rely on the birth control mandate have reason to fear that it—and other essential preventive care for women enshrined in the ACA, if not the health care law in its entirety—will be an early casualty of Donald Trump’s administration. When I called a handful of OB-GYNs across the country in December, many said that since the election they’d been inundated with patients requesting IUDs, hoping to prepare for the reproductive dark age that they fear is to come.

Trump’s choice to head the Department of Health and Human Services, Georgia Republican Rep. Tom Price—who wants to repeal the entire ACA—has famously justified his opposition to the contraceptive mandate by denying that any woman could possibly struggle to pay for birth control without it. “Bring me one woman who has been left behind. Bring me one,” he said in 2012. “There’s not one.”

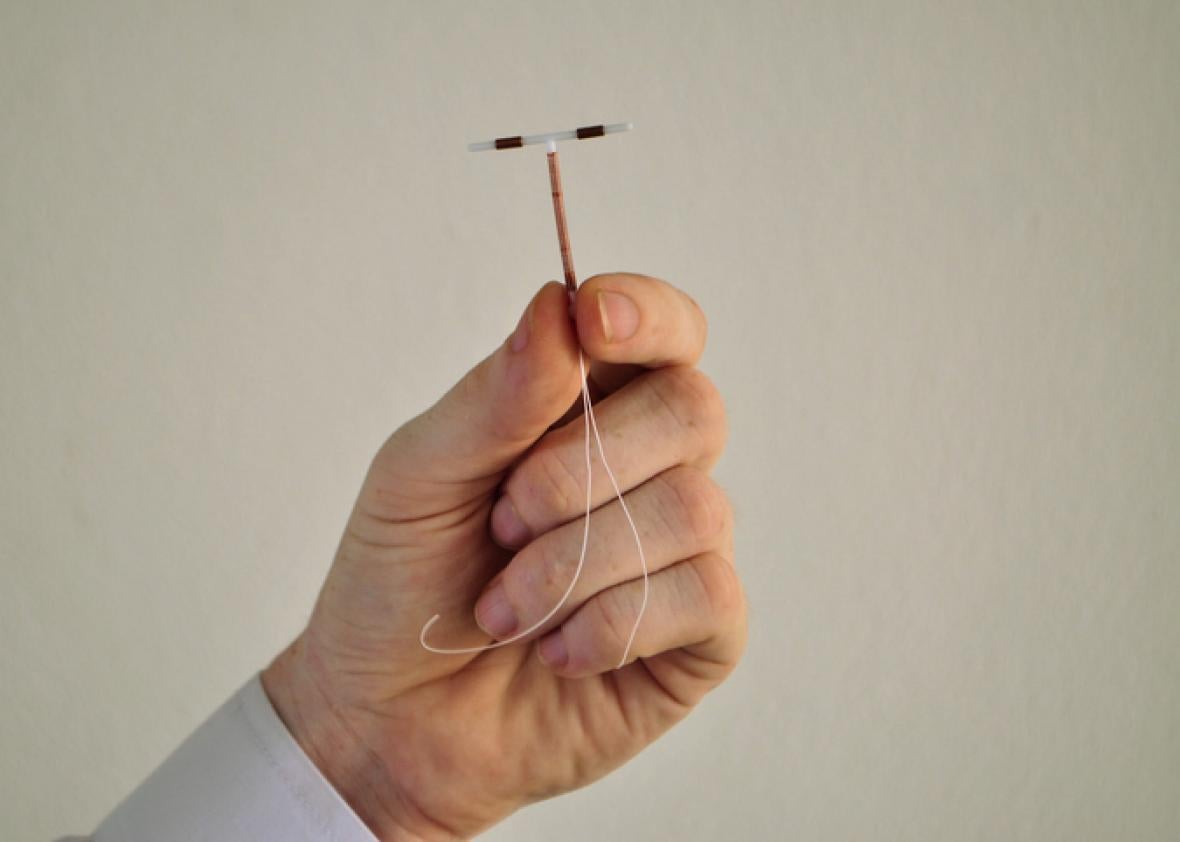

The data disagrees with him, and this September’s issue of Health Affairs—largely lost amid the hubbub of the campaign—contains the strongest evidence yet that reducing costs has helped more women access birth control. One study found a 2.3 percent increase in women using prescription contraceptives (from 30 percent of women to 32.3 percent). Notably, “A disproportionate share of this increase came from increased selection of long-term contraception methods” such as IUDs, which cost a prohibitive $500 or more on insertion before the elimination of copays but which are 22 times less likely to fail than the birth control pill.

Larger copays lead to less consistent—and, thereby, less effective—birth control use, according to another study in Health Affairs. “For many women, what can lead to an unintended pregnancy is not that they don’t use contraceptives, but inconsistent use,” says Adam Sonfield, senior policy manager at the Guttmacher Institute. “Only two-thirds of at-risk women use their method consistently and correctly.” It’s hard to ensure that a woman remembers to take her pill at the same time every day, but the mandate sought to eliminate situations in which a woman might be forced to choose between covering her birth control copay and making her rent. Since the ACA went into effect, this kind of erratic usage has decreased “slightly but significantly,” according to the study.

The simple fact of free birth control has had a ripple effect, as women relate their experiences to friends and family members. Jennifer Conti, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University who has written for Slate, told me she’s noticed that her patients know more about their choices than they did a few years ago. “I think people are talking about all options right now on an equal playing field,” she said.

Since the election, those social networks are buzzing with anxiety. Aisha Mays, the medical director of the San Francisco Department of Public Health’s teen community health program, told me her patients’ fears don’t always account for California’s progressive laws around access to birth control. “Because we’re seeing this national message around limiting and repealing coverage, patients are accepting that message, even if it doesn’t apply to them,” she told me. “My worry is that that will translate into patients not coming in to access medical care that they actually have, that they’re actually covered for.”

What will be covered going forward remains unclear. Congress doesn’t have to repeal Obamacare for Trump and Price to ax the contraceptive mandate: The ACA requires the coverage of “preventive services for women” without cost-sharing, but the list detailing which services qualify is a matter of HHS guidance. That means Price’s HHS could strike the inclusion of birth control on his first day in charge. (The same goes for the other covered services, which include well-woman visits, HIV screening, domestic violence counseling, and breast-feeding supplies.) If this happens, insurance companies will almost definitely continue to cover birth control, with cost-sharing: Most states have laws on the books requiring that contraceptives be treated like any other prescription drug, and, as Sonfield says, “covering contraception is industry standard at this point.” But the eradication of the mandate would have disproportionate consequences for low-income women, who also have the hardest time ending an unwanted pregnancy or supporting an unplanned-for child. For many people, the return of copays would also put the most effective contraceptives—IUDs and long-acting implants—out of reach.

Which is why, in OB-GYN offices across the country, it’s not bells but frantic phone calls that are ringing out 2016. Anne Davis, a doctor who can see Trump Tower from her Manhattan office, told me she’s ordered roughly double the usual number of IUDs to meet patient demand since the election. Planned Parenthood reported a nearly tenfold increase in women seeking IUDs in the first week after the election, as well as “an unprecedented surge in questions about access to health care and birth control, both online and in our health centers,” according a statement from chief medical officer Raegan McDonald-Mosley.

This surge has left some providers feeling conflicted. “When a woman chooses a method that is in line with her goals and her preferences, 70 percent of those women use that method correctly,” says Mays. Though there’s reason to believe that time is running out to take advantage of the birth control mandate, Mays worries about the sense of doom driving women to make hasty or uncharacteristic decisions. “We want women to choose the method that’s best for them,” she says, “not to choose a method out of fear.” No one can predict the events of next year, but as long as this much-beloved policy persists, millions of women maintain one crucial form of control.

Read more of Double X’s 2016 year-in-review coverage.