Over the past several years, the conventional wisdom on contraception has shifted in favor of the intrauterine device. Doctors and patients, no longer deterred by memories of the flawed and dangerous Dalkon Shield, are embracing devices that are 22 times less likely to fail than oral contraceptives and also happen to be the greenest form of birth control on the market. State legislatures are even beginning to consider IUDs as public health investments: Colorado’s free and low-cost long-acting contraception (LARC) program cut the state’s teen pregnancy rate nearly in half, saving taxpayers boatloads of money. Now Delaware is giving away free ones, too.

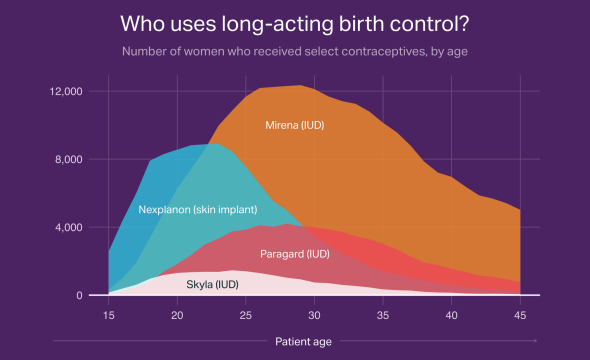

But IUDs and their less-common LARC-mates, hormonal skin implants, still represent a small proportion of U.S. birth control use. From 2009 to 2012, the Guttmacher Institute found, the proportion of women on birth control who chose LARCs rose more than 3 percentage points, which brought it to just 11.6 percent. And according to a new report from doctor-database site Amino, IUDs are most popular among women in their 30s, even though the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended IUDs over the pill and over any other form of contraception for teen girls.

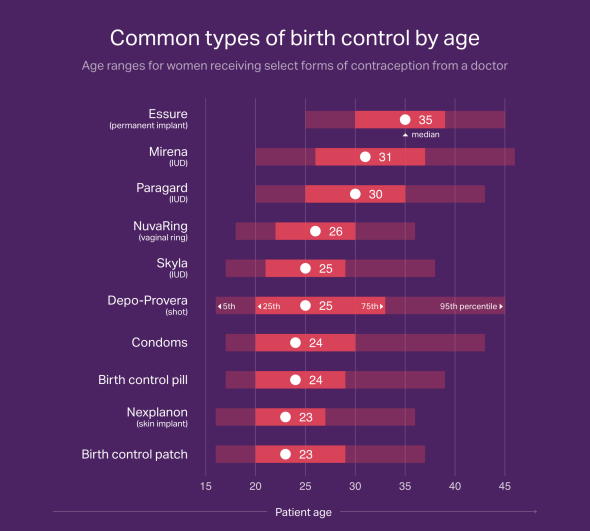

Using data from the private insurance claims of 620,000 women who visited doctors for birth control in 2014 and 2015, Amino found that younger women prefer birth control pills, patches, skin implants, and shots to IUDs. The median ages of women using the two most common IUDs, Paragard (copper) and Mirena (hormonal), were 30 and 31, respectively.

The median ages of women using the other two LARCs on the market, the Skyla hormonal IUD and the Nexplanon skin implant, were considerably lower: 25 and 23, respectively. Skyla is specifically marketed to young women because it’s smaller and contains a lower dose of hormones than Mirena. Both Skyla and Nexplanon may be more popular among younger women because they last only for three years as opposed to Mirena’s five and Paragard’s 10. Even though a doctor can remove an IUD at any time, the concept of committing to a birth control method for five or 10 years could be intimidating to a teen or young adult who doesn’t know how she’ll feel about kids or sex in a couple of years.

But the number of women who choose Skyla as their birth control method is a tiny fraction of the number who use Mirena or Paragard, and those are still tiny fractions of the number of women who use birth control. So why aren’t more young women choosing IUDs? Some are scared of insertion pain, which varies widely from patient to patient, making it hard for doctors to give potential IUD recipients peace of mind.

There has also been a traditional view among health care providers that IUDs are only appropriate for women who’ve had children. That perception has been debunked, but it’s hard to shake, in part because Mirena is technically only Food and Drug Administration–approved for women who’ve had children, though plenty of doctors prescribe it for those who haven’t. One OB-GYN professor told me that she suspected Mirena was only initially tested on women who’d given birth because researchers wanted to play it safe with a population of women who met a certain threshold of reproductive health and whose uteruses were definitely big enough to fit an IUD.

Perhaps because of this perception, IUDs are relatively popular with women who’ve given birth, according to Amino’s report. In 2014 and 2015, 1 in 5 women who received an IUD did so right after having a baby, usually on the same day as the birth or during a postpartum visit six-or-so weeks after delivery. Another population that loves LARCs: women’s health care providers. A 2015 study found that a full 42 percent of family planning doctors on birth control choose IUDs and implants, more than three times the proportion of women in general. “The pill” has become shorthand for birth control in pop culture and most social circles—if doctors want to encourage their patients to use the most effective form of contraception, they might need to make “the LARC” happen.