In this unprecedented era of menstrual activism, invention, and public discourse, it was only a matter of time before period talk reached outer space. Last week, in a report published in Npj Microgravity, researchers made one of the first scientifically backed recommendations for astronauts who menstruate.

Hormonal contraception makes it possible for women to halt their periods, but with the prospect of yearslong space missions looming, the authors of the paper advise against taking birth control pills. The bulk of hundreds or thousands of days’ worth of oral contraception and their packaging would create unnecessary weight and waste on the ship, and scientists have not studied the long-term effects of deep-space radiation on hormonal pills. Thus, the researchers recommend long-acting reversible contraception like an intrauterine device or arm implant—preferably the former, since the latter might catch on or otherwise interfere with space garments.

The male-dominated astronautics community has touched on the issue of menstruation in spaceflight before, but discussions often relied on sexist assumptions and unchallenged misconceptions. Some officials wondered why women needed to be considered for space missions in the first place. In 1971, as NPR reported last year, a NASA paper about psychological issues for astronauts suggested women be used as stress-relief tools:

The question of direct sexual release on a long-duration space mission must be considered. Practical considerations (such as weight and expense) preclude men taking their wives on the first space flights. It is possible that a woman, qualified from a scientific viewpoint, might be persuaded to donate her time and energies for the sake of improving crew morale; however, such a situation might create interpersonal tensions far more dynamic than the sexual tensions it would release.

In this climate, menstruation was pegged more as an emotional liability than a physical one. According to Cecil Adams at the Straight Dope, “several plane crashes in the 1930s had involved menstruating female pilots, and experts—male experts, of course—suggested that putting a woman with ‘menstrual disturbances’ in the cockpit was an invitation to disaster.” Once women did make it to the top of the U.S. astronaut program, scientists worried that menstruating in microgravity might cause menstrual fluid to flow upwards, from the uterus into the Fallopian tubes and out into the abdomen. They predicted that this phenomenon, called retrograde menstruation, could cause endometriosis, a painful syndrome wherein uterine tissue grows outside the uterus.

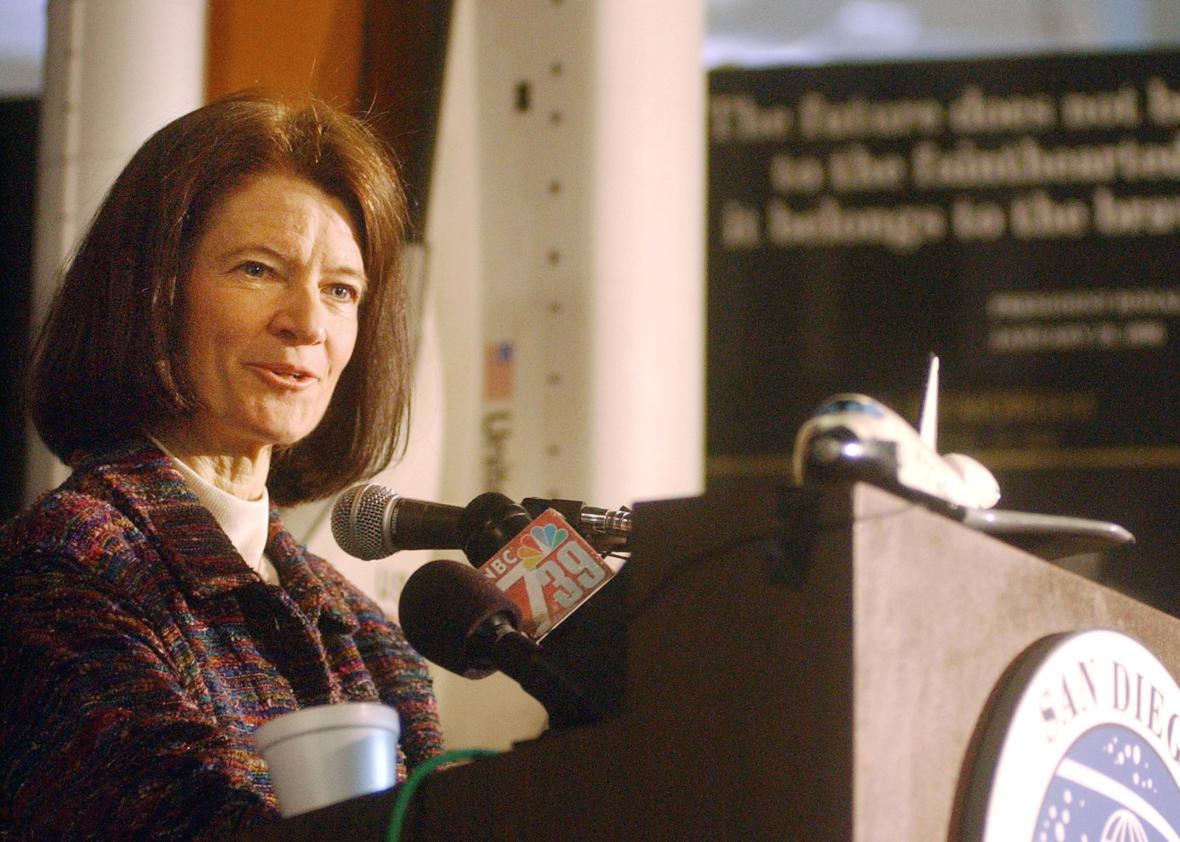

Astronaut Rhea Seddon, who flew in the ’80s and ’90s, says no one commissioned a study to prove or disprove this theory, which she and her fellow female astronauts found absurd. “We said, ‘How about we just consider it a non-problem until it becomes a problem?’ ” she recounted in an oral history. They continued: “‘If anybody gets sick in space you can bring us home. Then we’ll deal with it as a problem, but let’s consider it a non-problem.’”

There is no evidence that retrograde menstruation could occur in microgravity, nor that, if it did, it would cause endometriosis. Women who’ve menstruated in space have all reported that everything went fine, just like menstruating on the ground. That makes sense: No doctor has ever suggested that women should not do cartwheels, lie down with their hips raised, or perform yoga inversions during their periods, which would exert a greater negative force on the contents of the uterus than zero-gravity would.

Still, for purposes of travel weight, waste disposal, and astronaut comfort, suppressing menstruation as recommended by last week’s report seems to be the best option. But there is one major downside: It might deprive the men of NASA of a significant learning opportunity. Just before Sally Ride became the first U.S. woman in space, the mission’s male engineers, who took it upon themselves to design a makeup kit for her, asked her how many tampons she’d need for a one-week mission. “Is 100 the right number?” they asked. “No,” Ride answered. “That would not be the right number.”

One IUD can last for up to five years, thankfully making candy-jar guesses from clueless scientists a thing of the past.*

Correction, Apr. 26, 2016: The post originally misstated the length of time a hormonal IUD can last.