It’s been a week since the New York Magazine cover story “The Retro Wife” hit newsstands, and its merits (or lack thereof) are still being debated. Two of the feminist stay-at-home moms featured in the story—Kelly Makino and Rebecca Woolf—spoke to Tracie Egan Morrissey at Jezebel about how they felt misrepresented by the piece. Woolf, it seems, has more of a case than Makino. It’s strange that she would be used as an example of a feminist “stay-at-home mom” in the first place, since she has a full-time job: running her blog, Girl’s Gone Child.

The source of the confusion and feelings of misrepresentation might lie in the inadequacy and general clunkiness of the term “stay-at-home mom.” Technically Woolf stays at home, and is a mom. But she’s also self-employed, and that important nuance isn’t relayed by the SAHM label (I am also technically a SAHM, but work 40 or more hours a week). I’ve always disliked the term. It connotes “shut in” to me, as if mothers who don’t do paid work are too fragile to handle the outside world. How did this become the default terminology for women who don’t go to an office every day?

According to the etymology expert and University of Minnesota professor Anatoly Liberman, the term “stay at home,” without the mom or dad tacked on, is very old. (Liberman recalls seeing the term in Dickens.) “Stay at homes” were people who didn’t travel. The “mom” part didn’t start becoming attached to the phrase until the ‘80s, and it didn’t grow really popular until the ‘90s, says Rebecca Jo Plant, an associate professor of history at UC San Diego and the author of Mom: The Transformation of Motherhood in Modern America. The New York Times did not use the phrase until 1992, and even then it was in quotes.

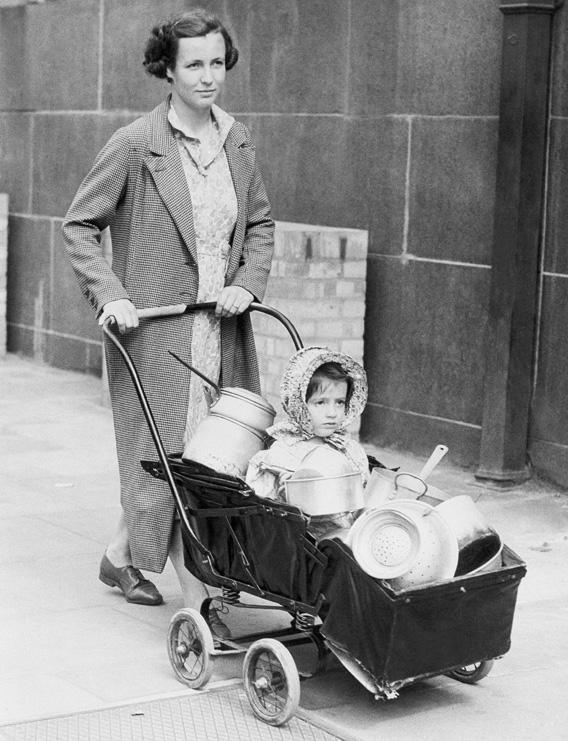

Earlier in the 20th century, “housewife” was the preferred term, but as the Victorian focus on efficiency and sanitization began to shift in the 50s, a new word—“homemaker”—came into vogue. The mid-century popularity of “homemaker,” says Plant, “reflects the rise of a therapeutic culture in the twentieth century, when advice literature to women began to stress the importance of meeting the emotional and psychological needs of children and husbands.”

“Homemaker” had pretty thoroughly replaced housewife by the 1970s, but it was already sounding old-fashioned by the ‘80s. Enter the “stay-at-home mom.” No one I spoke to could tell me definitively why the term became ascendant; Plant speculates, “My sense is that their usage reflects the notion that the most important thing that the woman who stays home actually does is to focus on her children and foster their development, with an increasing emphasis on intellectual/cognitive development.”

Both “housewife” and “homemaker” connote domestic drudgery like toilet scrubbing (which no one really wants to do). “Housewife” in particular emphasizes an old-fashioned devotion to the husband, while “stay-at-home mom” shifts the focus onto the children. “It’s probably no coincidence that the term ‘playdate’ as we currently use it also takes off,” during the 80s and 90s, Plant muses. “You can’t really perform domestic labor when you’re attending or even hosting a playdate.”

Though it’s impossible to say if “stay-at-home mom” (and let’s not forget “stay-at-home dad,” equally lame) beat out other aspirants for referring to parents who don’t do paid work, Plant’s research shows that this kind of terminology is ever-changing. Which means we, as a culture, are free to come up with a new word to refer to stay-at-home parents. Primary caretakers is the only thing I could come up with, but it sounds a little stiff and census-y. Any other suggestions?