Racked with tuberculosis, the patient lost 1,400 pounds in two weeks. That’s excessive weight loss even if you’re an elephant. For Packy, a senior citizen at the Oregon Zoo, the situation was critical. Veterinarians at the zoo started the pachyderm on an 18-month course of the same daily antibiotics that millions of people around the world who suffer from the bacterial infection take. The United States is currently in the midst of an elephant tuberculosis epidemic. There have been more than 60 confirmed cases of tuberculosis in U.S. elephants—in a population of only 446. In June, a third elephant was diagnosed with tuberculosis in the Oregon Zoo, and this past November an infected elephant died in a California refuge.

The disease poses risks not just for the large land mammals but also for us. While most infectious diseases are not easily passed between species, tuberculosis is an exception. The bacteria can be transmitted by close contact or by droplets containing bacteria that float through the air after a sneeze or cough. Our current animal practices are driving the present epidemic.

Tuberculosis, like its vintage companions pertussis, measles, and mumps, was once all but gone from the United States. It re-emerged in the 1980s, a comeback corresponding to increased injection drug use and the HIV epidemic. After reaching a peak in 1992, TB rates have been falling for two decades in North America. Elephants are the exception. The elephant reservoir of the disease represents a stronghold of the bacteria, a persistent reminder that we can’t eradicate this stubborn killer.

Tuberculosis is thought to have killed more people than any other disease—more than the plague, leprosy, cancer, or HIV. It’s estimated that one-third of the world’s population is infected with the bacteria. The disease kills 1.5 million people every year. While the disease, then known as consumption, was running rampant through Paris in the 19th century, a French military doctor, Jean-Antoine Villemin, established that the disease could be passed between humans and cattle. It was a remarkable realization, especially considering that the bacteria responsible for the disease had yet to be discovered.

Tuberculosis is caused by a curious group of bacteria called Mycobacteria. The microorganisms have a slick, waxy coat, allowing them to float in the air like a hazardous balloon. These tiny balloons are inhaled and make their way to the lungs. The bacteria thrive in the moist, oxygen-rich environment. After a few weeks, a person runs out of immune defenses and the bacteria grow unimpeded in the empty spaces within the lungs. The bacteria are particularly good at getting out again. The disease produces dry, heaving coughs that fling the tiny invaders out of the body. Hours after an infected person has left a room, the bacteria hang on, waiting for their chance to infect someone else, their waxy coats allowing them to bob in the air.

The treatment for TB is a 6- to 9-month course of antibiotics. Unfortunately, the drugs we have are beginning to falter. The same waxy coat that helps the bacteria fly through the air also helps the microorganisms develop resistance. Multi-drug resistance to our current antibiotics is on the rise throughout much of the world. The therapy also isn’t cheap. The cost runs typically $2,000 per patient. For an elephant, the price tag rises to $50,000.

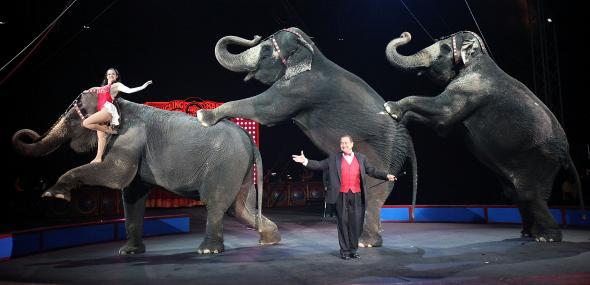

On April 13, 1796, the first elephant to grace North America since the ice ages arrived by boat in New York City. For two bits, onlookers could gaze upon the majestic beast. The animal was sold to Hackaliah Bailey, a farmer in Somers, New York, and the first American circus was born. No one could predict that one day a human disease would threaten the very existence of elephants on the continent.

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

The first hint that TB might be a serious problem for elephants in North America came in 1996, when four Asian elephants owned by the Hawthorn Circus Corporation became ill. Three of the four elephants succumbed to the infection, and 11 keepers were found to harbor the bacteria, one of whom had an active infection. The elephants had been spread out around the country, leased to different circuses and zoos. Over the next decade, infected elephants began popping up all over the United States. As TB swelled in elephants, the humans in contact with them also found themselves at increased risk. In 2000, at the Los Angeles Zoo, 55 keepers tested positive, their bacteria a genetic match to the infected animal they handled—strongly implying, but not proving, that the keepers had acquired the infection from an elephant. When the USDA investigated, it found patient zero: an 11-year-old Asian elephant who died in 1981 at an animal facility in Richmond, Illinois. Aware that it would be impossible to track all 22 members of this index herd, by now spread far across the country, the federal government instead took immediate action. (The USDA would later learn that 41 percent of the animals from the Richmond facility were positive for TB.)

The USDA established new safety guidelines for TB testing in elephants and issued a temporary moratorium on elephant travel. At the same time, accusations over the elephant epidemic began to fly. In a 1998 court case, a private investigator working for Feld Entertainment, the parent company of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey, testified that, “I was told by [the circus veterinarian] … that about half of the elephants in each of the shows had tuberculosis, and that the tuberculosis was an easily transmitted disease to individuals, to human beings.” These claims have never been substantiated but may have spurred the government agency to ensure regular TB testing. USDA guidelines dictate that once a year, elephants in the United States should have their trunks washed out with saline to get a sample to be analyzed. Blood antibody tests are also performed. But even these monitoring measures are not without flaws. The procedure itself is challenging, and the culturing the bacteria from these specimens has not proven reliable. Consequently, elephant managers don’t always know which animals are contagious, and the epidemic is worsening. Treating an elephant for TB has proven complex, with multiple cases of resistance to first-line human therapies, as well as difficulty in administering the drugs themselves and controlling their toxicity.

The problem started, strangely enough, with the Endangered Species Act, which led to restrictions on elephant imports into the United States. In response, the Disney Corporation, Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus, and Busch Gardens developed large elephant breeding facilities. Elephants are difficult to breed in captivity. Females have low rates of fertility, and there are limited numbers of mature males. The population in the United States has never been self-sustaining. Michael Fouraker, executive director of the Fort Worth Zoo, emphasizes the problem by saying: “Current breeding rates suggest that in 45 years, only 50 female elephants may populate zoos … without successful elephant births in the coming years, the North American Asian elephant population will face near-extinction.” With the pressure on, corporations established the first artificial insemination program for elephants. They also began breeding-loan programs in which zoo and circus animals were shipped all over the country. With animals moving far and wide, the stage was set for a disease outbreak.

In 2009, the first elephant-to-human transmission of TB was confirmed. In an outbreak in Tennessee, the bacteria were transmitted from a single elephant to nine keepers at an animal refuge. There is still much we don’t know about transmission between our species. In the Tennessee outbreak, some employees who were not in close contact with the infected animal still became infected. We can’t be sure how, possibly simply by sharing the same air.

TB isn’t a disease that’s typically transmitted from animals to humans. It usually happens the other way. Humans are the natural habitat for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. When animals become infected, it’s called “reverse zoonosis.” Cows, pigs, birds, meerkats, mongooses, and monkeys have all succumbed to the human bacteria. While a related bacterial species, Mycobacteria bovis, has been transmitted from cows to humans, usually by unpasteurized milk, elephants stand alone as the only recently documented cases of zoonotic transmission of M. tuberculosis.

This past April, Packy celebrated his 52nd birthday with a 40-pound cake. The elephant-friendly dessert was made with whole-wheat flour, fruits and vegetables, and five pounds of butter. Despite the celebration, Packy struggles with his infection. He has trouble taking his medication, suffering from a range of side effects and drug sensitivity. He’s not alone; millions of people have difficulty taking the therapy. The challenges mount in senior citizens like Packy, who is the oldest living North American elephant raised in captivity. In 1962 his birth caused a stir, as he was the first elephant born on the continent in 44 years. The newborn elephant made global headlines and was featured in an 11-page spread in Life magazine. Now he’s making headlines again, as four of the eleven people closest to him have tested positive for TB. He lives with his son Rama, also infected with TB, but who seems to be responding to medication. This one pachyderm family in Oregon highlights our vulnerability, both to the deepening tuberculosis crisis and to zoonotic outbreaks. How we respond is an important indicator of our and their future susceptibility to infectious disease.