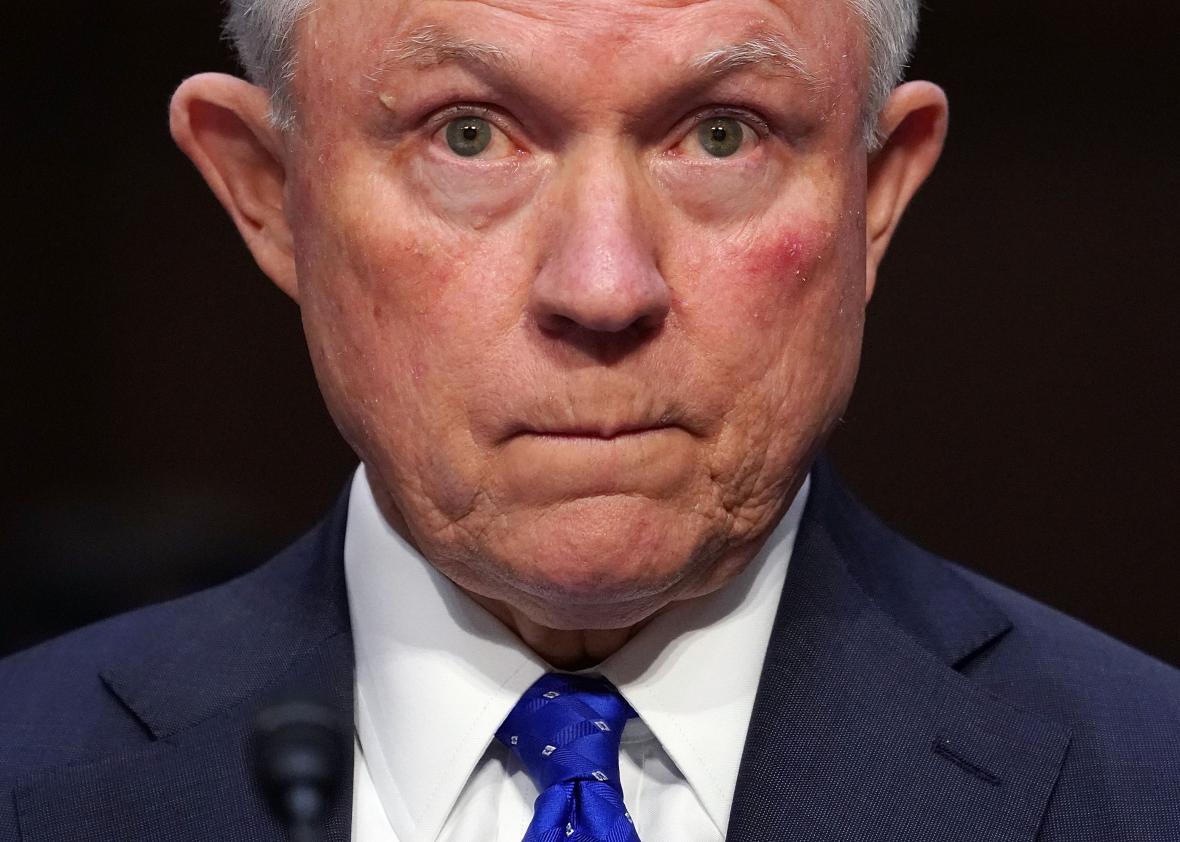

Executive privilege was a running theme during Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Wednesday.

Sessions began by saying that he’d received a letter from minority members of the committee asking him to state whether the president would be asserting executive privilege at this time. He then refused to answer the question—a de facto no—while declaring that he also wouldn’t be answering questions about his conversations with the president … based on the possibility the president might eventually assert executive privilege. This is important for so many reasons.

The critical question is whether Sessions and other Trump administration officials are allowed to indefinitely stonewall congressional interlocutors on issues that might be pertinent to possible high crimes committed by this president. Sessions wants to make Americans think this issue is very complicated. It’s not.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse demonstrated how the Trump administration is using obfuscation, “nonassertion assertions” of executive privilege, and Republican control of the Senate to evade the truth.

In June, Sen. Kamala Harris had the starring moment during Sessions’ appearance before the Senate Intelligence Committee when she was shushed for attempting to get the attorney general to say under what legal basis he was refusing to answer his former colleagues’ questions. Whitehouse on Wednesday finally got Sessions to acknowledge that legal basis: A 1982 executive memo from President Ronald Reagan.

Here’s a transcript of that moment:

Whitehouse: Let me ask if the Nov. 4, 1982, letter by President Reagan is still the guideline under which the department operates or have you changed that guideline.

Sessions: That is a part of the principles under which we operate under, yes.

Whitehouse: It is the document that describes how the executive branch will respond to executive privilege, correct?

Sessions: Well it’s that and case law and other executive documents that have been issued over the years.

Whitehouse: Let me know if any of this has changed. That rules says that “executive privilege will be asserted only in the most compelling circumstances and shall not be invoked without specific presidential authorization.” Is that still the rule?

Sessions: Executive privilege cannot be invoked except by the president.

Whitehouse: “Congressional requests for information shall be complied with as promptly and as fully as possible, unless it is determined that compliance raises a substantial question of executive privilege.” Is that still the rule?

Sessions: That’s a good, good rule.

As Whitehouse pointed out, that guideline—the one under which Sessions conceded he’s operating—allows for a period of abeyance during which executive branch departments can hold off on responding to congressional inquiries to determine whether the president wants to invoke executive privilege. The president should then assert executive privilege, or the departments should provide the requested information. That period of abeyance has extended months with no end in sight.

During testimony in June, Sessions and other administration officials refused to answer questions about reported presidential behavior that could be evidence of obstruction of justice. These questions included whether Trump was considering pardoning former campaign officials under investigation in the Russia probe and whether he was asking officials to intervene against that probe. Again, these are questions about whether the president of the United States may have committed a felony. Trump officials’ blanket response was that they couldn’t answer because he might one day assert executive privilege (but not today).

The reason for this dance is this: If executive privilege is asserted, it can be challenged in court. The Supreme Court has never ruled on whether Congress can compel testimony about private conversations with the president. But the major precedent on executive privilege was a unanimous opinion titled United States v. Nixon in which the court held that the president does not have the right to an unlimited assertion of executive privilege. In that case, President Richard Nixon was trying to use his executive privilege to conceal evidence that he had committed obstruction of justice. Almost immediately after the court forced that evidence to light, he resigned.

Again, this is all very simple and Sessions was doing his best to make it seem complex. During Whitehouse’s second round of questioning, he meticulously laid out the key issue of abeyance:

What I’m worried about is that this administration is de facto rewriting Ronald Reagan’s executive order about executive privilege so that the period of abeyance has no end to it and Congress is stonewalled on information without ever getting an assertion of executive privilege, an assertion to which I believe we are entitled if we’re going to be prevented from getting information.

To this very simple statement, Sessions snickered and said, “As you’ve indicated, you have quite the ability to work your way through the complexities of this.”

He then claimed that the president hadn’t reached the point of asserting executive privilege. According to Sessions, this was because before the president could assert privilege he had to know specifically what he was asserting it for. Of course, these questions were first raised in Senate hearings in June and some of them were repeated to Sessions by Whitehouse on Wednesday. Sessions also invented a new rule about executive privilege seemingly on the spot and out of whole cloth.

“He also has a right to be informed as to why his privilege—[it] is of high value—and why it should be waived in exchange for the request and the reason the request is made,” the attorney general said in one of the least coherent answers of the entire session.

The reason the president is able to get away with preventing the truth about his possible obstruction of justice from becoming a matter public record—these issues have been reported in numerous anonymously sourced press accounts that Trump has deemed “fake news”—is also simple. Republicans control the Senate and Republican committee chairmen such as Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley and North Carolina Sen. Richard Burr control these committee hearings. Without them issuing subpoenas for this information and threatening to hold those who refuse to answer in contempt of Congress, President Trump can stall indefinitely without ever actually asserting an executive privilege that might be struck down in court.

As the New York Times noted in June, he wouldn’t be the first president to do this: The CIA refused to turn over the potentially privileged communications of President George W. Bush during the Obama administration, and Congress just ended up letting it go. As the Times also pointed out, it has been executive branch policy since 1989 that “only when … a subpoena is issued does it become necessary for the president to consider asserting executive privilege.”

As long as Burr is in charge of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Grassley is in charge of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and the Republicans control the United States Senate, the American people may never get these answers.