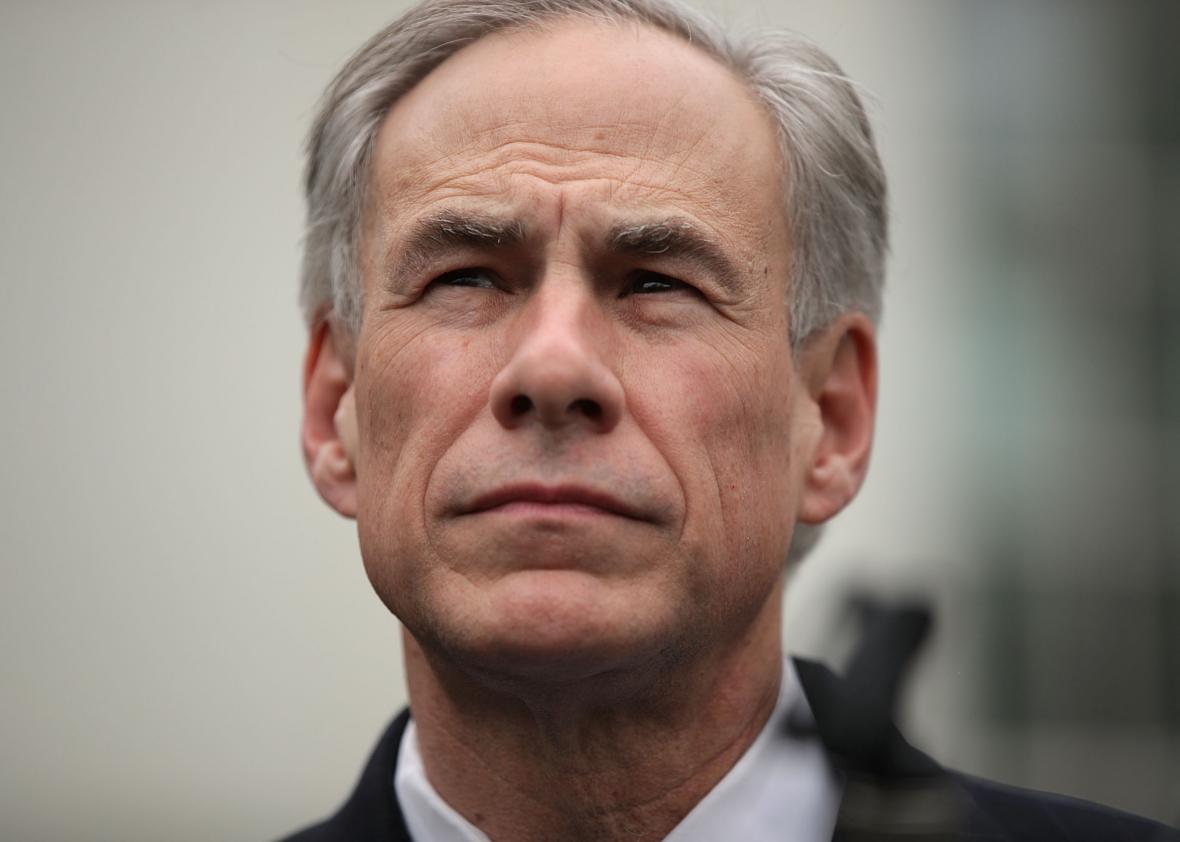

On Tuesday, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed SB8, enacting a slew of new abortion restrictions in the state. SB8 outlaws second-trimester abortions and bars anyone from helping a woman obtain certain abortions—including, for instance, driving her to a clinic. Moreover, the law mandates that abortion providers dispose of fetal tissue by cremating, burying, or “entomb[ing]” it. Hospitals will also be required to cremate or inter miscarried fetuses.

If this “fetal funerals” provision sounds familiar, that’s because Texas enacted it once before. It never took effect, however, as a federal court blocked the rule as unconstitutional. That injunction remains in effect. By reinstating the same basic regulation in a slightly different form, Texas is treading dangerously close to a conflict with a federal court order.

The history of Texas’ fetal burial rule is straightforward. Shortly after the Supreme Court struck down the state’s draconian restrictions on abortion clinics, the Texas Department of Health and Human Services proposed a new rule compelling clinics to bury or cremate fetal remains from abortions and miscarriages. Abortion providers promptly sued, alleging that this regulation imposed an undue burden on a woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy. The rule, these providers explained, would significantly increase operation costs for the clinic—expenses that would be passed down to patients. Texas, for its part, insisted that it envisioned fetuses being buried in a mass grave at a cost of just $2 each. (The state’s justification for the regulation? “Protecting the dignity of the unborn.”)

In January, U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks ruled for the plaintiffs, concluding that the regulation imposed burdens that “substantially outweigh” its benefits in violation of the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause. Sparks also found that the requirement was so vague that clinics could not be sure exactly what conduct it prohibited, another due process infirmity. He therefore enjoined the rule, forbidding Texas from enforcing it.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton appealed Sparks’ decision in late May. Just a few days later, however, Abbott signed SB8, which contains a provision that is nearly identical to the Health and Human Services rule. Yes, the regulation was enacted legislatively rather than through an agency, but that makes no difference to the constitutional analysis. The basic fact remains that, with SB8, Texas passed a law that has already been blocked by a judge.

Technically, SB8 does not directly conflict with Sparks’ injunction, which only prevents the state from implementing the Health and Human Services rule. In practice, though, the law looks a lot like defiance of a federal court order. By way of analogy, imagine if a court struck down Texas’ constitutional amendment outlawing same-sex marriage and the legislature simply replaced it with an identical statute. That game of whack-a-mole might be hypothetically legal, but it would also be constitutionally indefensible.

On Thursday, I asked the Center for Reproductive Rights, which represents the clinic plaintiffs, whether it would ask Sparks to expand his injunction to cover SB8. Although the group declined to comment on its “litigation strategy,” a senior staff attorney noted that Sparks’ January decision would seem to clearly proscribe a law like SB8. That suggests the Center for Reproductive Rights will soon return to Sparks’ courtroom to request yet another order, one that forces Texas to explain why it is once again targeting women’s constitutional rights with such a bizarre and burdensome regulation.