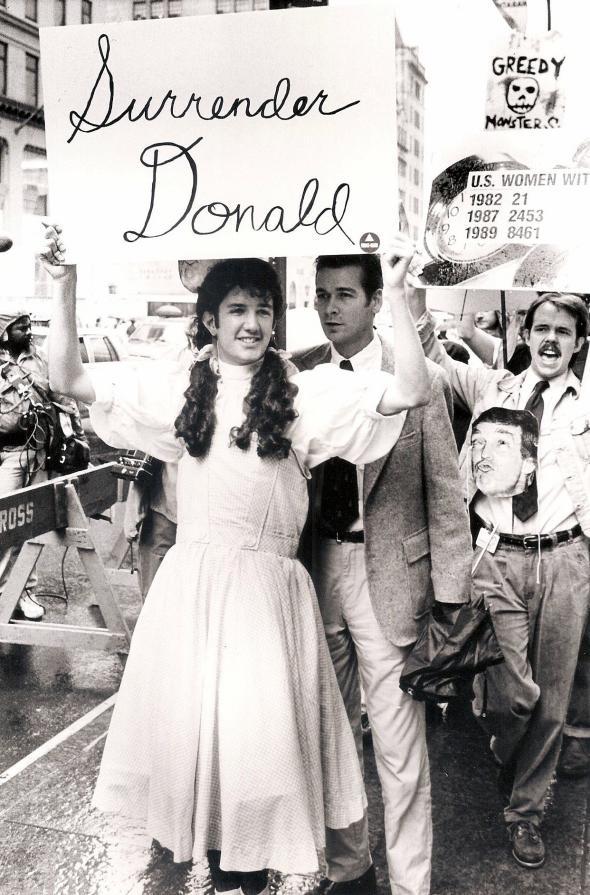

On Oct. 31, 1989, roughly 100 protesters from the AIDS activist group ACT UP New York descended on Trump Tower at 5th Avenue and 56th Street. One protester, dressed as Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, waved a sign demanding, “Surrender Donald.” ACT UP was in a fight for the lives of people with HIV and AIDS, striking out against government indifference and corporate greed. And they saw Trump for what he was: a monster in the making.

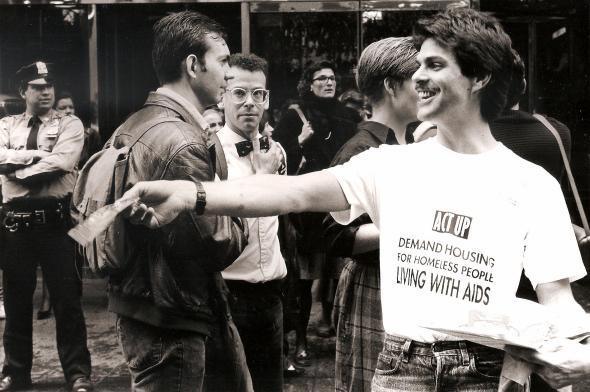

ACT UP, short for AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, had been formed two-and-a-half years earlier, out of mounting anger over inadequate city, state, and federal government responses to rising numbers of HIV/AIDS cases and related deaths. The group quickly became known for their disruptive, theatrical demonstrations, calling for expanded and faster drug research, more affordable medications, and greater AIDS education. The Trump Tower protest was organized by ACT UP’s Housing Committee, which hoped to draw attention to the lack of housing for homeless people with AIDS.

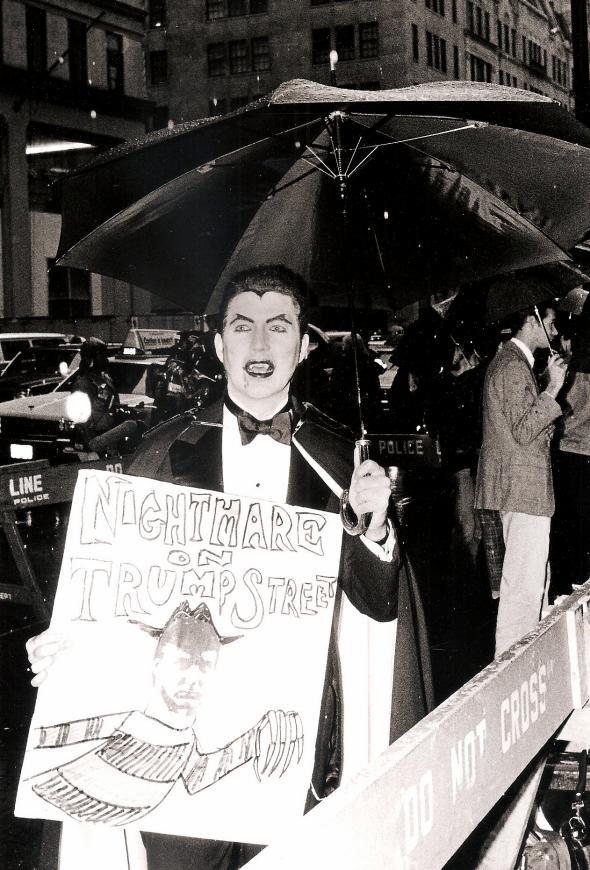

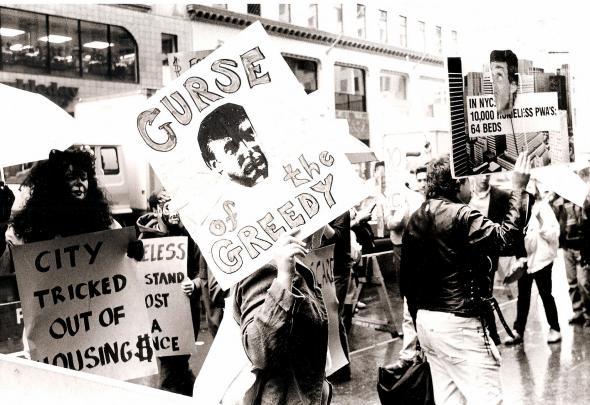

Photographs from the October 1989 Trump Tower demonstration give a sense both of its boldness and its humor. They were taken by photographer Lee Snider, who had been documenting LGBTQ life and politics in New York for the gay press since the 1970s. Through the rain, protesters maintained a picket line, carrying a range of printed and handmade signs: “Silence Equals Death,” “In NYC 10,000 Homeless PWAs, 64 Beds,” “Money For AIDS Not For Malls.” Two participants hung a banner, “10,000 Homeless With AIDS,” from the windows across the street.

It was Halloween, and the protest took on a special, sometimes ghoulish campiness. A flier featured the headlines, “New York Tricked Out of AIDS Care, Trump Treated to Tax Abatements,” and “Don’t Let New York Become a Ghost Town.” One participant wore a vampire costume and held a sign depicting Trump as Freddy Krueger, with the words, “Nightmare on Trump Street.” Others wore paper masks featuring Trump with his lips pursed. Eventually some protesters went inside Trump Tower where they threw fliers from the escalators, eluding security guards. In the end, the police put a stop to the protest and arrested six people on charges of illegal trespass, disorderly conduct, and resisting arrest.

Lee Snider

But 24-year-old Ronny Viggiani—the activist dressed as Dorothy—escaped capture. As the gay magazine Outweek reported at the time, police stopped the escalators with Viggiani at the top. Viggiani shouted, “You’ve got to turn it on, because I can’t walk [down] in these heels.” The police eventually relented, turning the escalator back on, and Dorothy floated down, like Glenda the Good Witch, as other protesters cheered.

* * *

I first came across Snider’s photographs of Dorothy and the 1989 Trump Tower protest a few weeks ago, around Halloween of this year, while doing research on ACT UP’s housing activism at New York University’s Fales Library. I smiled when I saw the images; I could not imagine at the time that Trump might actually win the election. I should have recognized the threat, and heard the urgency in the words “Surrender Donald,” as ACT UP protesters did in 1989.

Lee Snider

ACT UP saw in Donald Trump a symbol of a flawed system, where government policies empowered the wealthy at the expense of the poor and marginalized. They saw, as one poster put it, a “greedy monster,” and were among the few prescient and bold enough to draw their swords—not only for the sake of queer people but for a wider community of people living with HIV and AIDS, disregarded and disempowered by their government.

The group had first targeted Trump Tower a year earlier, on Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving, when wealthy shoppers could be expected to flock to the luxury stores in the building’s atrium. For ACT UP, Trump Tower was a garish symbol of the disparity between rich and poor in New York. Trump had received a $6.2 million tax abatement to construct the building. It was money, ACT UP argued, that might have been used to turn vacant city-owned buildings into housing facilities. As a flier succinctly put it, “Donald Trump gets richer while homeless people get sicker.” The 1989 protest at Trump Tower repeated many of the key points—a signal of how little had changed—how little except the rising estimates of homelessness among people with AIDS: 5000 in 1988, 10,000 in 1989, and a projected 30,000 by 1991.

Trump was hardly alone in benefiting from city policies that privileged wealthy developers. As the fliers, printed in English and Spanish, explained, “The city’s tax abatement policy is shamelessly political. … It favors the projects of the rich and powerful campaign contributors—the Zeckendorfs, the Helmsleys, the Chase Manhattan Bank—over those of grass roots service organizations.” But Trump was a canny choice: Trump Tower was completed in 1983, but by 1989, Trump had gained a new level of national prominence.

Lee Snider

On Jan. 16, 1989, Time featured Trump on the cover with a story titled, “Young, handsome and ridiculously rich, Donald Trump loves making deals and money, loathes losing and has an ego as big as the Ritz — er, Plaza”—a reference to his latest hotel purchase. The essay featured many choice (and tweet-length) quotes: “Who has done as much as I have? No one has done more in New York than me,” “I love to have enemies. I fight my enemies. I like beating my enemies to the ground.” It pointed to his many unethical, racist, and often illegal real estate practices; the construction of his three-story, onyx and gold-embellished home atop Trump Tower; as well as colorful insults lobbed at journalists who criticized him and politicians who blocked his construction plans.

By 1989, there were also hints that Trump had his eye on politics. In an interview on the Oprah Winfrey Show in 1988, he critiqued U.S. foreign policy and free trade agreements, in terms nearly identical to those he would use three decades later in his presidential run: “We are a debtor nation …and I think people are tired of seeing the United States ripped off.” And in the summer of 1989, Trump waged a campaign against the Central Park Five—five young black and Latino men wrongfully accused of raping a white woman—placing an ad in the New York Times calling for the death penalty to be reinstated. Their sentences were later vacated, but Trump, as late as October 2016, has stood by his actions despite DNA evidence. In other words, Trump in 1989 was already the man who would run for president in 2015—and ACT UP was already calling him out.

In the two weeks since Trump’s win, activists have organized demonstrations at Trump Tower and across the country, even as others have questioned the purpose of protest after the election. Commentators from the right and the left have dismissed the protests as hapless, ineffectual, or mere “whining.” Chicago Sun-Times columnist Mark Brown has suggested leftists forgo demonstrations until Trump takes office and a “clear issue” emerges: “Better now to stand down and stay alert and follow the sound guidance of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton to respect our democratic traditions and give Trump a chance to lead.” But the dangers posed by Trump and his supporters—to Muslims, undocumented immigrants, women, people of color, LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, people who are poor—are already clear. As ACT UP knew in 1989, the danger of bad government is not abstract or immaterial, but life or death.

Lee Snider

* * *

This week I tracked down Ronny Viggiani—Dorothy from the photograph—and we spoke on the phone. Back in the late 1980s, Viggiani was working at the library at the Fashion Institute of Technology, when a friend invited him to attend one of ACT UP’s regular Monday night meetings at the LGBT Center on 13th Street. When the Halloween protest was planned for Trump Tower, Viggiani thought of the beautiful Dorothy costume a friend had designed, either for Halloween or for a stage production—he couldn’t now recall—and decided to wear it to the demonstration. He created the sign by hand, “Surrender Donald.” The words were a reference to a scene in The Wizard of Oz, when the Wicked Witch of the West rides her broomstick over the Emerald City, and writes with smoke in the sky, “Surrender Dorothy.” Viggiani explained: “I did love The Wizard of Oz when I was a kid. I used to watch it all the time, and I have very vivid memories of watching it, some not so pleasant. When I was really young, I saw it, I was terrified of the scary parts, the witch, the flying monkeys.” In dressing as Dorothy and taking on Trump, you might say Viggiani was conquering his demons.

In the years after the protest, Viggiani continued to take part in ACT UP actions, but he also began working at the HIV clinic of the Community Health Project at the Center. And in 1992 he decided to go to medical school—eventually working in St. Vincent’s Hospital, and today, in medical education. Looking back, Viggiani marvels still at the creativity and intelligence of so many of ACT UP’s members, and its impact. As Viggiani told me, “It called attention to this epidemic in lots of different ways, it accomplished changes in public policy, and in drug treatment, and in identifying or recognizing that HIV existed in lots of different populations and not just one population.”

ACT UP was, in fact, a model of queer intersectional activism. As historian Tamar Carroll documents in her 2015 book, Mobilizing New York: AIDS, Antipoverty, and Feminist Action, ACT UP New York consisted largely of white gay men, but women and people of color quickly organized to be heard within the group. In its first year, ACT UP New York organized a separate Women’s Caucus, as well as a collective for people of color called the Majority Action Committee—a name recognizing that racial minorities, in fact, made up the majority of people living with HIV and AIDS. By the end of 1989, ACT UP New York also began collaborating with Women’s Health Action and Mobilization, most famously at a massive demonstration at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Since the election, both Donald Trump as well as Democrats like Bernie Sanders have criticized the Left for focusing too heavily on “identity politics” at the expense of the white working class. But the leadership of activist groups from ACT UP to Black Lives Matter (another queer-led movement) demonstrate that racial, gender, and sexual oppression cannot be separated from economic injustice. The housing crisis that ACT UP decried in 1989 at the door and on the escalators of Trump Tower was not the simple result of financial policies but of deeper prejudices against women, LGBTQ people, people of color, people who used intravenous drugs, and the poor—prejudices that rendered their struggles less important and less visible. There are clear parallels between ACT UP and Black Lives Matter: These are not movements about “political correctness” but about survival. Despite some recent claims the left is all rhetoric, Black Lives Matter, like ACT UP, has made clear and actionable demands, rooted in a fundamental understanding that poverty is most dangerous for people whose lives have been valued less.

I’ve felt and seen so much sadness these weeks since the election, but I also have a feeling Trump does not know the force and creativity of the movement building in response to his coming administration. The photographs of the Trump Tower protest in 1989 give me a sense of hope in the power of activism to make injustice visible and make change imaginable. In the humor, humanity, and courage of ACT UP, in the fantastic reversal of Ronny Viggiani’s 1989 poster, “Surrender Donald,” I hear a queer call to action: to team up in recognition of difference and make Donald Trump miserable. I see a hashtag #surrenderdonald when he tries to deport immigrants and their children, register Muslims, renew stop-and-frisk, roll back protections for women and LGBTQ people, or dress down a dissenting journalist. I hear a movement, “Surrender Donald,” demanding Trump stand down, give up the presidency, and return to reality television. I see a thousand Dorothys with signs in front of Trump Tower, and I hear cries at the steps of the White House. Surrender Donald. Surrender Donald. Surrender.