On tonight’s Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, police shoot and kill an unarmed black man. In the other episodes that have aired so far this season, a sometimes-cross-dressing killer was caught on video talking to himself about the murder; a white transgender teenager died at the hands of a group of black kids, one of whom was tried as an adult for the hate crime; and New York City child protective services workers were driven to deception to hide the fact that they were too overworked to protect vulnerable kids from neglect and abuse. This mixture of sex crimes, social justice, institutional failures, racial tensions, and ripped-from-the-headlines news stories is what SVU is known for, but in its 17th season, the show is a throwback. Not only is it the last of the Law & Order spin-offs still on the air, it’s also one of the last network shows to focus squarely on the real world.

It’s gripping television that grapples with important issues, but does the focus on sex crimes—which, as the narration famously informs us, are “considered especially heinous”—mean that it’s inevitably exploitative and fear-mongering? Showrunner Warren Leight, now in his fifth season on the show, doesn’t think so. The show sometimes “runs the risk of being—or seeming—exploitative,” he admitted when we chatted on the phone, but “the flipside of that is that a lot of the time it’s informative. A lot of parents have come up to me and said, ‘Thank God you did that episode; I watched it with my 15-year-old daughter, and it allowed us to talk about things we had never said.’ ” Leight himself has a daughter heading off to college next year, and after viewing episodes about sexual abuse on campus, they talked about drinking, frat parties, and other touchy topics. “I think we’re probably the only show talking about any of these issues,” Leight told me.

That’s pretty convincing, but some story lines get downright creepy—like the arc involving sadist and serial rapist/murderer William Lewis, which ran over six episodes between May 2013 and April 2014. SVU was pretty explicit about the horrific things Lewis, played by Pablo Schreiber, did to the women he kidnapped and abused. “Some people were legitimately disturbed by those episodes,” Leight admitted. They were also “by far the most popular” of the nearly 100 episodes in the Leight era. “I will say, unequivocally, the audience prefers the more overtly dangerous ones,” he says. It’s impossible to diagnose exactly why, of course, though Leight speculates that it could be that the mostly female audience finds it cathartic to watch “these disturbing guys get caught, as opposed to real life, where they often aren’t.”

The least successful episodes—which Leight measures by looking at how the audience grows or declines after the half-hour mark—tend to come when the fictional story is too close to the real incident that inspired it, or “episodes that I would call more politically correct, in the sense that we were more sensitive to not offending anyone. Those don’t hold the audience’s interest quite as much, it seems,” he says. Given that storylines almost always involve topics like rape or marginalized groups like transgender people, the producers have to employ more sensitivity than the average writers room—and Leight admits that he feels “a much bigger responsibility” at SVU than he did at the other shows he’s worked on, such as Law & Order: Criminal Intent.

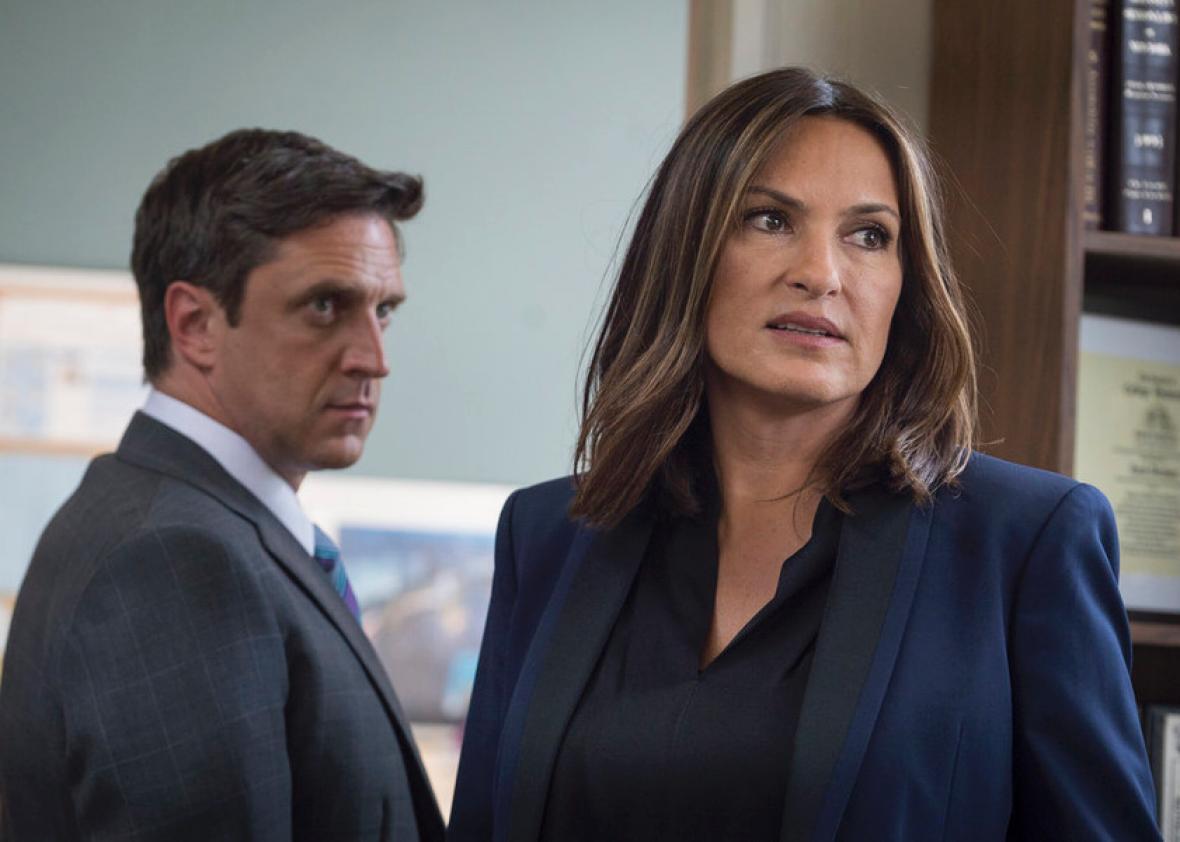

Photo by June Thomas

Of course, this means that SVU hears from more aggrieved parties than most shows do. Typically, they receive both praise and complaints from the groups they portray. “Transgender Bridge,” this season’s second episode, about the death of a trans teen, “got a lot of nice response … and some people were very upset within the transgender community,” Leight says. That mixed response is partly because “none of these communities are monolithic” and also because Leight and his team like to complicate issues: “If a show is purely educational, it ceases to be entertaining; it feels didactic or preachy. You may have an episode that everyone in a special-interest group approves of, but nobody watches.”

The producers’ biggest challenges are avoiding repetition—after more than 370 episodes, that’s getting harder every week—and keeping up with the times. They can return to a topic that’s been covered in the past as long as attitudes or awareness have changed. That was the case with “Transgender Bridge,” which was “a response to the number of transgender teens who have been bullied or killed.” In 2015, “our cops are more aware of it and more understanding about a kid having made these choices. Some of the kid’s friends are understanding, and her parents are understanding, which is something that would not have happened in 2003, I don’t think. … That was an episode that would not have made sense 12 years ago, or eight years ago, or maybe even six years ago.”

Another area where Leight was keen to stress that the show’s attitudes have changed is male rape. “That even trusted police [officers] would use the threat of male rape to get guys to confess—as if that was acceptable—was disturbing to me. That was always the macho cop move in the first several years of the show. Imagine saying that in any other context!”

In general, though, network politics cause more headaches than sex and violence. Although Leight did an episode involving a dentist who drugged and raped his patients that was a thinly veiled take on the Bill Cosby case, he says, “I don’t think I could have done a pure Cosby episode; that would have been complicated for NBC.” (Incidentally, that was a rare week where no one complained, because, Leight speculates, “dentists are not a threatened interest group, so they didn’t feel singled out.”) The NFL is another touchy area “There is no bigger moneymaker for all network television, and we went there twice since I’ve been here”—an episode about concussions causing dementia and a domestic violence case. “Nobody’s asked me to do a lot more of those, though.”