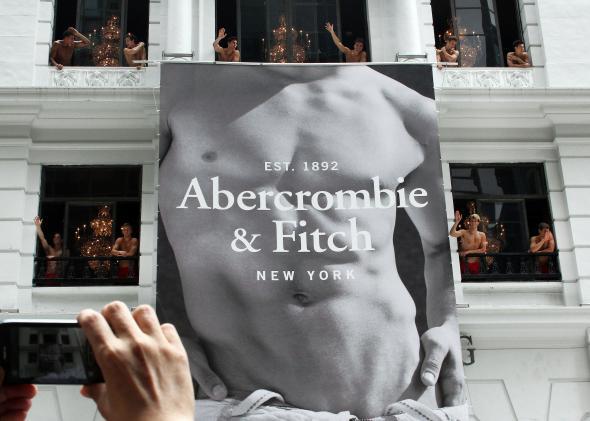

On Tuesday, news broke that Mike Jeffries, CEO of cool-kids fashion retailer Abercrombie & Fitch, was stepping down after more than 20 years leading the company. A gay man, Jeffries was credited with reinvigorating the brand, after he took over the company in the 1990s, by foregrounding a vision of effortless (and yet extremely gym-facilitated) masculinity—think images of shirtless, well-muscled (usually white) frat bros horsing around with the garden hose. The youthful marketing worked, at least for a while—A&F boasted profits well into the aughts—but in recent years, sales have flagged due to changing tastes that now disdain logos on garments and favor more affordable “fast fashion” purveyors like H&M.

Much of the coverage of Jeffries’ departure has focused on his eccentricities, and for good reason. The man was widely considered creepy for the strict dress and grooming practices he required of his handsome male employees, and, as Benoit Denizet-Lewis reported in a 2006 Salon profile, Jeffries was thought to exhibit OCD-like tendencies by many who knew him. It’s no secret that Jeffries had very specific ideas about beauty, which did not seem to offer much space to people of color or to a range of body shapes and gender expressions. Denizet-Lewis described the aesthetic thusly:

Much more than just a brand, Abercrombie & Fitch successfully resuscitated a 1990s version of a 1950s ideal—the white, masculine “beefcake”—during a time of political correctness and rejection of ’50s orthodoxy. But it did so with profound and significant differences. A&F aged the masculine ideal downward, celebrating young men in their teens and early 20s with smooth, gym-toned bodies and perfectly coifed hair. While feigning casualness (many of its clothes look like they’ve spent years in the washing machine, then a hamper), Abercrombie actually celebrates the vain, highly constructed male.

Shifts in the company’s strategy seem designed to correct some of this exclusiveness, particularly in the inclusion of larger sizes. Additionally, customers will apparently no longer be greeted by shirtless models at store entrances, and I would not be surprised if the famously homoerotic bag designs became more muted in 2015.

Is it wrong to be somewhat sad about that? While I have no personal feelings regarding Jeffries’ corporate leadership, I do want to briefly acknowledge just how important having a font of gay imagery in every American mall was to gay men of my cohort. As a colleague aptly put it, “The Abercrombie catalog taught me to be gay.” If the brand’s homoeroticism is toned down in the wake of Jeffries’ departure, gays of a certain generation will see a touchstone of their sexual youth fade into the past—so let’s remember it fondly for a moment.

Back in middle school and high school, A&F’s images—most of them produced by photographer of male nudes Bruce Weber—felt like sharply rendered external projections of desires that still felt very unfocused in my mind. I designate images specifically, because the clothes didn’t matter so much; I’m not sure I ever owned more than perhaps a T-shirt. But I recall a mixed feeling of excitement and fear when I, shopping with my family or friends, would approach the booming, heavily scented store. It was as if the toned-torso ads (or, occasionally, the toned-torso humans) that decorated the doorways would somehow implicate me in something I didn’t quite yet understand but secretly sensed that I liked. While I knew that the brand wasn’t really meant for me—a husky, straight-A band geek who thought little about clothes—as a consumer, something felt completely right about it on the level of sensibility.

Beyond the mall, encountering an Abercrombie bag in some stranger’s hand on the street was (and continues to be) a startling experience. Though the world is increasingly tolerant of the idea of gay people, actual same-sex desire continues to be a risky thing to express in public. And yet, each of the erotically charged images of young men, suffused as they were with a gay male gaze, felt like a tiny explosion of queerness in an otherwise straight environment. It’s chic to be down on capitalism these days, but this example of brand loyalty weirdly overcoming bigotry is a limited argument in its favor.

Of course, Jeffries wouldn’t agree with any of this. As Denizet-Lewis reported, the CEO saw nothing “gay” about his company’s image: “I think that what we represent sexually is healthy,” he said. “It’s playful. It’s not dark. It’s not degrading! And it’s not gay, and it’s not straight, and it’s not black, and it’s not white. It’s not about any labels. That would be cynical, and we’re not cynical! It’s all depicting this wonderful playfulness that exists in this generation.”

Regardless of Jeffries’ protestations on the subject, A&F’s homoerotic golden age was important to many gay men. But the truth may be that, like the garment plastered in logos, the time of the secret, coded gay thrill may be coming to an end. There’s obviously a lot to celebrate in not needing that sort of thing as much anymore—but then again, life’s less explicit pleasures are sometimes the most charming.