The concept of animus has proved critical to the resolution of the same-sex marriage issue. Indeed, animus was the centerpiece of last year’s decision in United States v. Windsor, in which the Supreme Court struck down the federal prohibition against recognizing legal same-sex marriages. Judges and commentators alike thought the reasoning in Windsor would dictate a similar outcome in the pending challenges to state-level marriage bans. But instead, at least two federal judges have managed to conclude that there is no animus present in these cases.

I was at first pleased to see my work cited in one of these opinions, Judge Jerome Holmes’ concurring opinion in Bishop v. Smith. But I was disheartened because the opinion had nonetheless ignored my central argument. It was discouraging yet again to then see Judge Martin Feldman citing Holmes’ reasoning to uphold Louisiana’s gay marriage ban. Given the increasing importance of animus in gay rights jurisprudence, I think it’s worth clarifying what does and doesn’t qualify as unconstitutional animus.

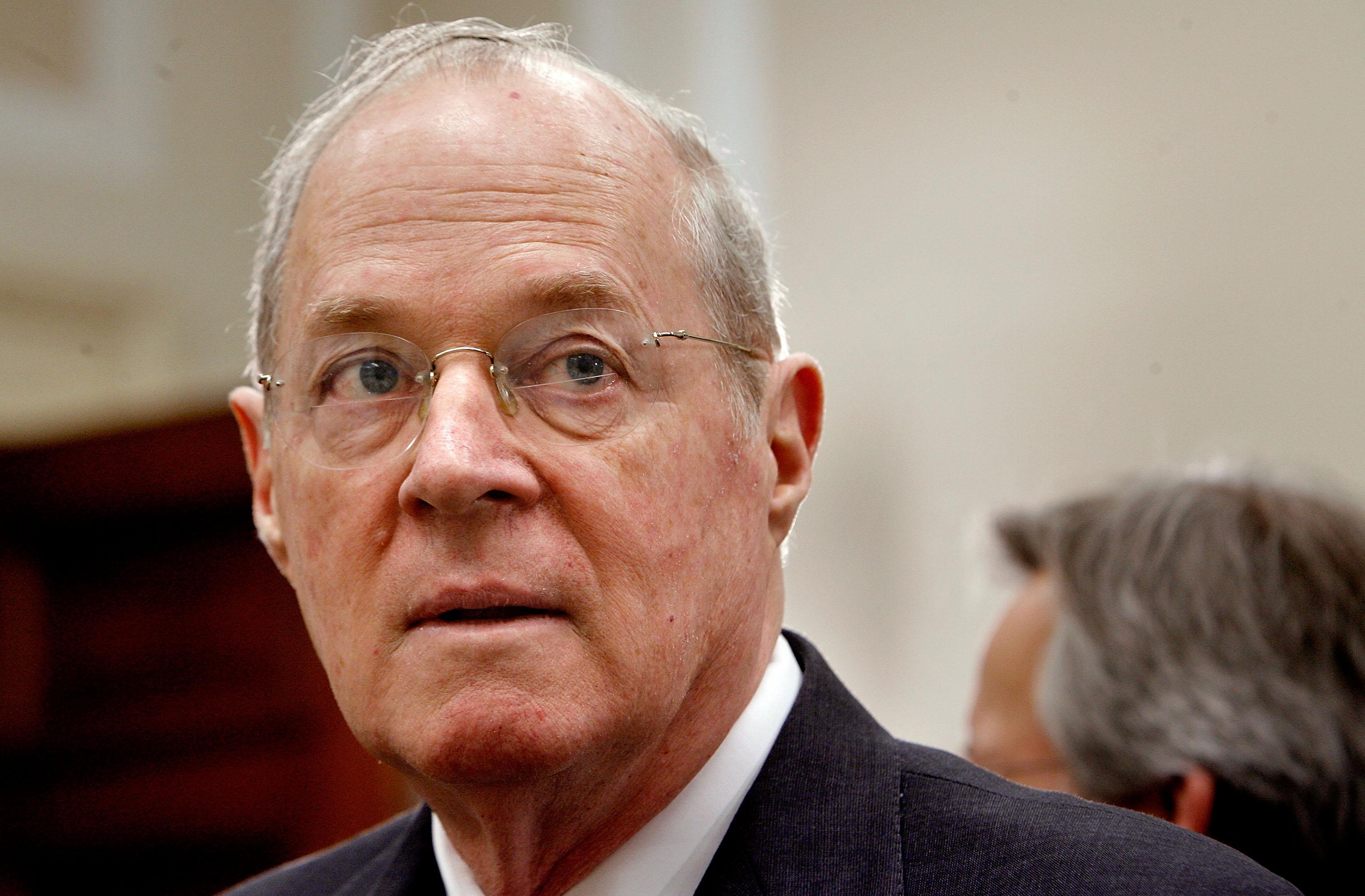

In his decision, Judge Feldman upheld Louisiana’s prohibition against same-sex marriage in part because he was hesitant to adopt “the notion that the state’s choice could only be inspired by hate and intolerance.” Judge Feldman reasoned further that the laws could not possibly be based in animus because they were the product of “a statewide deliberative process.”

This logic flies in the face of established Supreme Court precedent. First, Judge Feldman was wrong to equate animus with “hate and intolerance.” It is true that when the Supreme Court first addressed the issue in a 1973 decision called Moreno, it characterized animus as “a bare congressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group.” But this is only one example of what may constitute impermissible animus.

When we think of animus, we think of its most common meaning, which is hostility. But in broader terms, animus also means simply impetus—the force that makes something happen. It is this understanding of animus that the Supreme Court employs. In so doing, the court has held that there are several forms of animus that are impermissible from a constitutional perspective. For example, a law based on private bias, fear, stereotype, or mere negative attitudes should trigger concern that impermissible animus may be afoot.

Second, Judge Feldman makes the faulty assumption that laws subject to a “deliberative process” cannot at the same time be based in animus. This directly contradicts the premise of perhaps the most important equal protection decision of all time, Carolene Products. In that case, the Supreme Court carefully explained that the very purpose of the equal protection clause was to protect demographic minorities from the tyranny of the majority—a tyranny that is a necessary risk of our majoritarian political process. The deliberative process contains no safeguards against disadvantaging an unpopular minority. Rather, such an outcome is a routine possibility in a system where the majority always prevails.

Third, Judge Feldman characterized animus as a form of impermissible subjective intent held by the proponents of a law. In supporting this theory, he quoted at great length Judge Holmes’ concurring opinion in Bishop. In that opinion, Holmes held that state-level gay marriage bans do not exhibit animus, insisting that “the hallmark of animus jurisprudence is its focus on actual legislative motive.” In support of this argument, Holmes cited my 2012 article on the subject of animus.

But Holmes misunderstands the core of my argument—and ignores critical precedent. In two important animus decisions—Palmore v. Sidoti and City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center—the court found impermissible animus even though there was no evidence that the governmental actors in those cases themselves held bias against the targeted group. Rather, the laws at issue were deemed invalid because government actors were responding to prevailing biases in society.

The court in Palmore famously stated:

The Constitution cannot control such prejudices, but neither can it tolerate them. Private biases may be outside the reach of the law, but the law cannot, directly or indirectly, give them effect.

This is the question courts should be asking when they examine the constitutionality of state-level marriage bans. Not whether state legislators or the electorate acted out of hatred or bigotry, but whether the function of such laws is to express private bias against same-sex couples. A bare preference for opposite-sex couples over same-sex couples, absent any credible, logical, and independent public purpose, cannot justify a law in the face of an equal protection challenge.

Defining animus as a sort of impermissible subjective intent on the part of proponents of a law is also problematic from an evidentiary standpoint. It is extremely difficult to prove the subjective intent of a single individual, much less an entire legislative body or an electorate. Far better for the court to look at the deleterious effects of the law than to scrutinize the hearts and minds of a given law’s supporters.

If courts define animus as a “fit of spite” and require evidence of subjective ill will to prove its presence, they will render the doctrine virtually useless. Instead, courts—including the Supreme Court—should carefully examine all of the animus cases: not just Romer v. Evans and Windsor, but also Moreno, Cleburne, Palmore and the other related cases discussed in my 2012 article. The totality of this body of law presents a much more nuanced and complete portrait of the doctrine.

At a bare minimum, the courts have an intellectual and ethical obligation to address this full body of precedent and confront the notion that animus is something more nuanced and more constitutionally important than blunt hatred or bigotry. To date—and certainly in the opinions of Feldman and Holmes—this obligation remains unfulfilled.