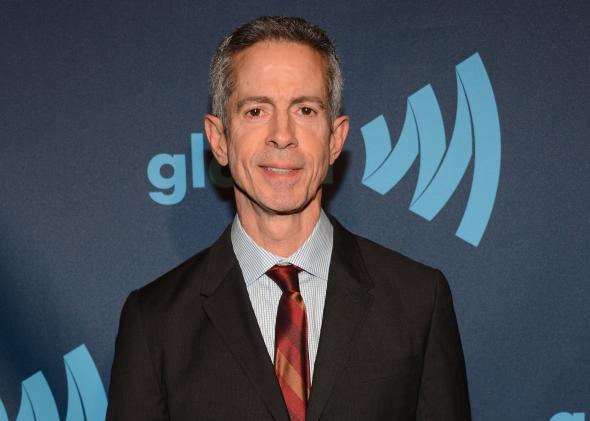

Truvada, the CDC-endorsed HIV-preventing miracle drug that nobody’s taking, has recently become a flashpoint in the gay community. While the medical community has largely supported the treatment, some gay rights advocates—including Dan Savage—have disparaged it as unsafe, idiotic, and even poisonous. On Wednesday morning, I spoke with Peter Staley, an early champion of HIV/AIDS activism and one of the heroes of the documentary How to Survive a Plague, about his views on the drug.

Mark Joseph Stern: Good morning. You’ve been a defender of—

Peter Staley: Did you see that interview with Larry Kramer in the New York Times?

Stern: No, I haven’t seen it yet.

Staley: He says taking Truvada is cowardly. [Sighs.]

Stern: Well, let’s start there. What are your views on Kramer?

Staley: I love him. I view him as a father figure. I have since he sparked ACT UP, which saved my life and millions of other lives. But I do worry that he’s stuck on a very kind of 1992 message around AIDS, and I worry how that’s going to resonate with today’s younger activists. Or just with today’s gay youth. I don’t think it speaks to the crisis as we face it today. Activism always has to change with the times and the circumstances.

Because we don’t have the death and dying that forced a drastic change in sexual behavior among gay men in the mid-’80s, which was largely sustained until the early ’90s, the safe-sex condom code that we created then has collapsed. And that’s the reality we live in today. Just talking about it, telling people that they’re cowards for not wearing condoms—I don’t think that’s going to create a mass movement of putting condoms on.

Stern: Why not?

Staley: I just don’t think it resonates. It’s a message that will be dismissed. And therefore not have an effect. I think it’s the challenge of today’s activists to lower HIV infections. That’s our challenge. The goal is not condoms on dicks. The goal is fewer HIV infections. So how do we get there? What’s the quickest path? What’s the path that takes human nature where it is today? And takes our culture for where it is today? And adapts to that and saves lives?

If somebody from my generation, the safe sex generation, can show me the cultural and advocacy path to getting gay men to return to the condom code that was developed in the ’80s, I’m all ears. But none of them have spelled that out. All they do is preach. None of them have a plan. A feasible plan, that leads us back to those norms. In the absence of the death and dying that changed our behaviors back then, there is no plan.

And so my strong response is: Well then, what the hell do we do now? And we have answers. We have biomedical tools. We can have honest discussions about risk-taking. And we can continue to strongly defend and promote those who use condoms. We have test and treat. We have treatment as prevention. We have PrEP, we have PEP, and we have a much more powerful community with which to engage all these issues. And we can engage public health officials on the task of implementing all these ideas.

Stern: Are you concerned that once gay men start taking PrEP, they’ll simply stop using condoms?

Staley: First off, there’s no evidence of that yet. Certainly there’s a possibility that it will feed into the trend that is well on its way. Almost a majority of gay men had abandoned condoms prior to PrEP hitting the market. None of this addresses them. How can we save them? What can we give them? And so to advocate for withholding PrEP from that 50 percent because it might play a role in enlarging that group to 55 percent is just lousy public health.

Stern: Why do you think PrEP remains so unpopular?

Staley: It’s a single reason in my mind. Everybody looks at costs of Truvada, fears of toxicity—those are all the challenges and questions facing the person who has already decided to look at this option. That’s not the underlying problem. The problem is that very few people even consider the option. And the reason for that is HIV-related stigma. Today’s younger gay men have decided that the way to avoid becoming HIV-positive is to believe that HIV is not their problem. And they’ve constructed some very false beliefs that it’s an older generation’s issue, that as long as they’re looking for HIV-negative men to sleep with, they’ll be safe.

And so the idea of considering the reality of their HIV risk, and the fact that some other gay men actually do that—that puts them in a category of, well then, you must be very, very slutty. Because that’s the only reason you’d have to think like that.

It’s all about the stigma. As long as I’m only being sexual to find my next boyfriend, I’m not that guy that’s sleeping around, and I really am not at much of an HIV risk. It’s such a sad story. It’s such an ’80s story. Nobody wants to go there mentally. You can’t consider Truvada unless you think about HIV/AIDS—and no one wants to think about it anymore.

Maybe I’m too cynical now and a lot of younger people do consciously think about this. But I don’t know. I think it’s something a lot of people have an unwillingness to consider. There’s this impulse to push it out of their minds, to not have those discussions, to not think deeply about it, to not think of it as their generation’s problem. And all of that thwarts the next steps, which is—OK, well, what kind of prevention techniques do I want to adopt that make sense?

Stern: What can activists do to encourage gay men to take Truvada?

Staley: It’s going to have to come from within the younger generation. And frankly, it starts with the Truvada whores. What a beautiful movement. Here are the guys who are coming out. Coming out has been the secret ammo for the LGBT movement from Day 1. Whether it was coming out as gay or lesbian, or HIV positive, or having AIDS, or now just announcing how you’re protecting yourself against HIV/AIDS. All of that courage is what ultimately can change hearts and minds and gets a discussion going. When there’s a critical mass of young gay men willing to discuss this publicly and keep that discussion going amongst their peers, it will become increasingly hard for the other 95 percent to keep their heads in the sand. I don’t know when we’re going to get to that point or if we’re going get to that point. I have learned not to underestimate the stigma. It gets worse every year among gay men. and I’ve become very cynical about our prospects at being able to reverse that. So my dirty little secret is that I’ve been incredibly vocal about being pro-PrEP, but I have no illusions that it’s going to become a widely adopted prevention mechanism because of the stigma.

I’m disgusted by the anti-PrEP rhetoric. And if that rhetoric had won the day, we would be completely lost in this fight. It remains so anti-science—including Larry’s comment, calling Truvada poison—and should be called out as such. I think we’re winning now. The anti-PrEP side sounds so hysterical that I really think we’re beginning to at least win the argument with the AIDs establishment, the medical community, and government policy—and in our online debates. But I still remain very skeptical that we’re going to break through HIV stigma. I almost spit out my tea when I saw the New York Times predict that there could be 500,000 prescriptions for this soon. It’s not going to happen. Or it’s not going to happen quickly until we can somehow break through the stigma.

Stern: Are you optimistic that Truvada will become more popular?

Staley: No. I’m banking more on test-and-treat, treatment as prevention, than I am on PrEP. We should be dramatically ramping up treatment and flattening the treatment cascade. With fourth-generation HIV tests, we can catch HIV earlier after infection, create programs that make it very easy for anyone who tests positive to get into care, to get hooked up with a good doctor or clinic, to get them on treatment and undetectable. And if we get a high percentage of Americans who are HIV-positive but undetectable, we’ll dramatically lower the rate of HIV infections. You’re fixing it from the back end rather than the front end. You fix it by really concentrating on those who are HIV-positive, including those that don’t know it and those who are newly positive, while not abandoning the efforts to reach those who are HIV-negative and at risk.

It’s something we always have to keep working on. The stigma has made the front end work frustratingly inefficient. It always comes down to the stigma.