Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau conquered the internet last Friday when a video of him answering a reporter’s question about quantum computing went viral. But that victory may have come a little too easily.

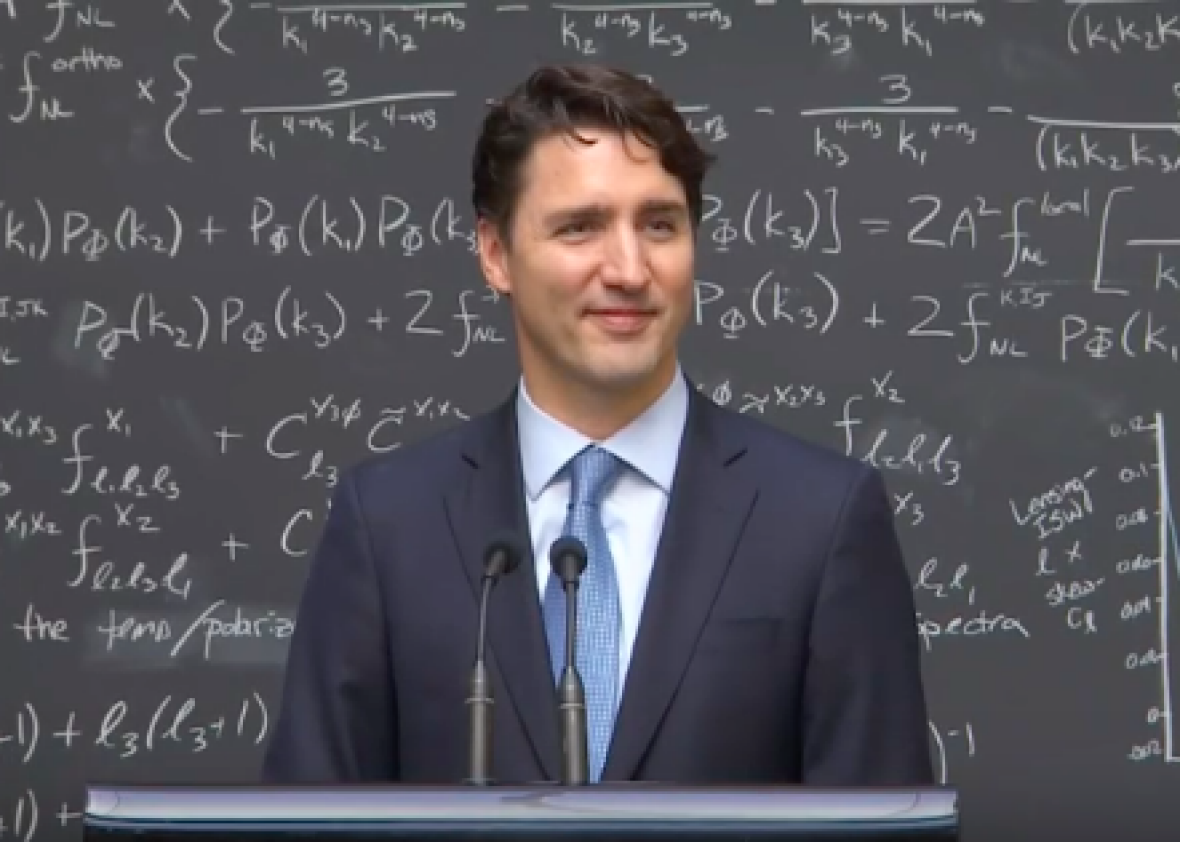

The optics could not have been more perfect for a young head of government* whose intellect is often overshadowed by his head of hair. Holding a press conference after he toured a theoretical physics institute, Trudeau stood in front of a blackboard full of intimidating equations as a reporter jokingly asked him to explain quantum computing—and he proceeded to do just that. “Very simply, normal computers work by … ,” he began, before the crowd’s laughter drowned him out. “No, no, no, don’t interrupt me,” he broke in, with the sort of patient smile one flashes when called at the card table while holding the nut flush. “When you walk out of here, you will know more.”

Trudeau proceeded to deliver a brief yet authoritative-sounding riff on the difference between bits and qubits that seemed plausible enough to draw cheers from the audience and smiles and nods from the scientists flanking him. And it was all captured in a video ready-made for liking and sharing.

The media did not need to be told what to do with this video. The Facebook-optimized headlines practically wrote themselves. And so the Internet of Takes whirred into action, each outlet driven like one of John Herrman’s eerie automaton GIFs to crank out its own variant on the narrative that would inevitably engulf social media and rain viral traffic on all involved:

- “Justin Trudeau Gives Snarky Reporter a Lesson in Quantum Computing”—the Huffington Post

- “Canadian Prime Minister Schools Journalist in How Quantum Computing Works”—the Verge

- “A Reporter Tried to Stump Justin Trudeau With a Question About Quantum Computing, and Got Royally Trud-Owned”—Fusion

As is customary when partaking in such social-media feeding frenzies, each blogger added to the story a dash of his or her own speculation, thereby nominally differentiating it from rivals’ offerings, and from the bare facts at hand. The video proved that the handsome PM was “more than a pretty face,” one observed. “Everyone should be able to explain quantum computing like Justin Trudeau,” another opined. The Verge take, ironically, began with the line, “As a journalist, I’ve learned never to assume anything.” (Next lesson: Never say never.) Yes, Slate partook too, and I’ll admit that I may be biased when I say I found my colleague’s post suitably breezy and charming in a way most others were not. (“Passable” is certainly a more accurate assessment of the quality of Trudeau’s explanation than “perfect” or “brilliant,” as Konstantin Kakaes points out at the Washington Post.)

In any case, it wasn’t just the Blogs. CNN, Reuters, CBC News, and others posted their own versions of the video, their headlines all hewing to the prevailing framing.

You can probably guess where this is going. Over the weekend, even as latecomers continued to dine on the story’s rapidly decaying scraps, a somewhat different picture began to emerge. A Canadian blogger pointed out that Trudeau himself had suggested to reporters at the event that they lob him a question about quantum computing so that he could knock it out of the park with the newfound knowledge he had gleaned on his tour. And so Monday brought the countertake parade—smaller and less pompous, if no less righteous—led by Gawker with the headline, “Justin Trudeau’s Quantum Computing Explanation Was Likely Staged for Publicity.”

But few of us in the media today are immune to the forces that incentivize timeliness and catchiness over subtlety, and even Gawker’s valuable corrective ended up meriting a corrective of its own. Author J.K. Trotter soon updated his post with comments from Trudeau’s press secretary, who maintained (rather convincingly, I think) that nothing in the episode was “staged”—at least, not in the sinister way that the word implies. Rather, Trudeau had joked that he was looking forward to someone asking him about quantum computing; a reporter at the press conference jokingly complied, without really expecting a response (he quickly moved on to his real question before Trudeau could answer); Trudeau responded anyway, because he really did want to show off his knowledge.

Trotter deserves credit, regardless, for following up and getting a fuller picture of what transpired. He did what those who initially jumped on the story did not, which was to contact the principals for context and comment.

But my point here is not to criticize any particular writer or publication. The too-tidy Trudeau narrative was not the deliberate work of any bad actor or fabricator. Rather, it was the inevitable product of today’s inexorable social-media machine, in which shareable content fuels the traffic-referral engines that pay online media’s bills.

What’s remarkable is just how readily and unwittingly we bend reality to that machine’s imperatives. The laws of shareable content dictated that the interviewer be “sarcastic,” that the hunky prime minister be tired of not being taken seriously, that his answer be the Perfect Shutdown Response. We in online media have internalized these dictates to such an extent that we no longer even realize we’re applying them. (“As a journalist, I’ve learned never to assume anything.”) The Trudeau story is a perfect, gleaming artifact of a system in which truth is that which gets the most Facebook shares.

Not that journalistic truth has ever been altogether innocent of media economics. For Hearst, it was that which sold the most newspapers; for investigative journalists, it might be that which wins Pulitzers; for the nightly news, it’s what bleeds. False and faulty narratives today just move faster, farther, and with what seems like a little less human agency along the way.

*Correction, April 19, 2016: This post originally misidentified Trudeau as head of state. In Canada, the head of state is the monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. The prime minister is the head of government.