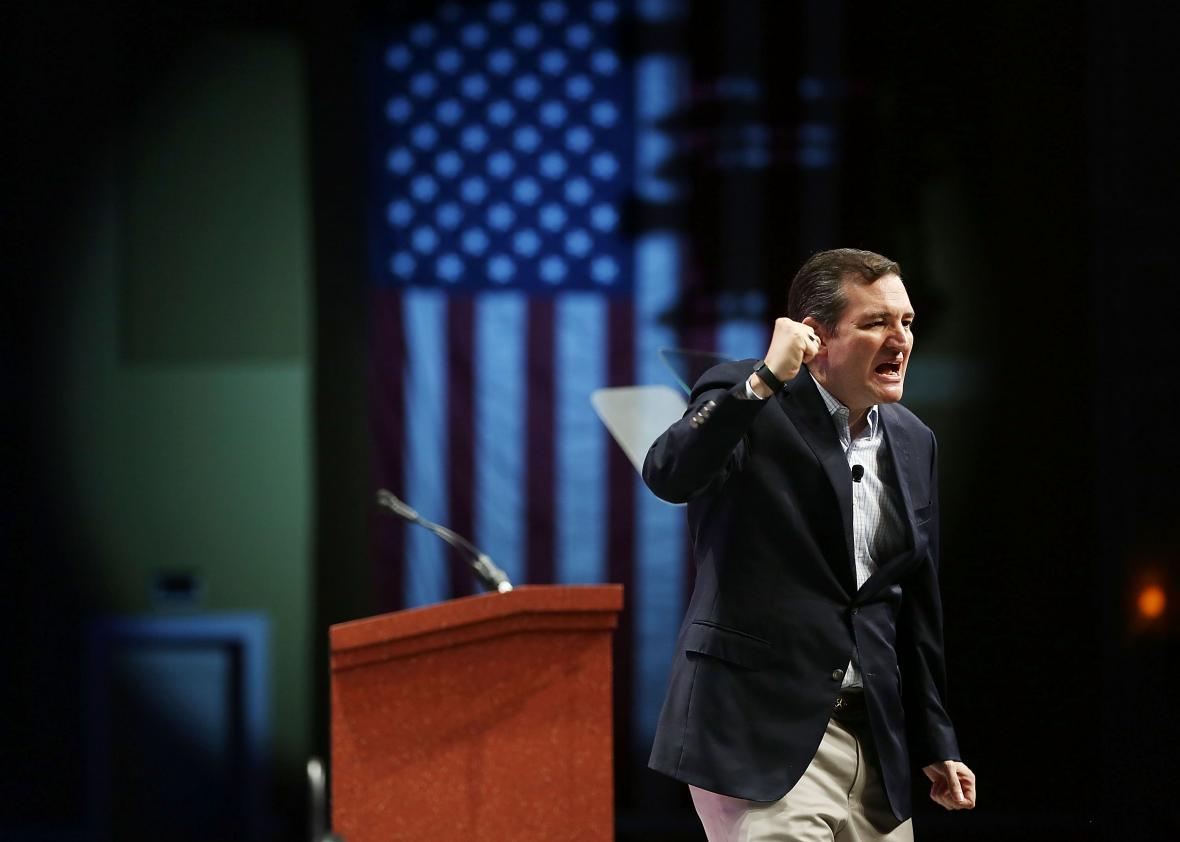

Sen. Ted Cruz has promised to abolish the Internal Revenue Service if he’s ever elected president, so you might fairly assume that his tax plan would be nothing but bleeding red meat for the political right. And yet the man’s proposal—which, depending on whom you ask, could cost the government anywhere from $3.7 trillion to $16.2 trillion over a decade1—has managed to spark a pretty lively argument among conservative policy thinkers, some of whom worry that it might accidentally set the stage for much, much higher taxes in the future should Democrats ever take back control of Washington.

Why the agita? Cruz would like to shred much of the existing tax code, eliminating the corporate income tax, the payroll tax, and the estate tax, while replacing today’s seven personal income tax brackets with a single, 10 percent flat tax. Unfortunately, even in the laissez-faire Candyland of the Republican imagination, the government would still need a bit of cash to keep Capitol Hill’s lights on. And so, in order to avoid bankrupting the United States entirely, Cruz would impose a new, roughly 19 percent “business flat tax.”2 This is his campaign’s creative rebranding of what the rest of the world typically calls a “value-added tax,” or VAT. And rationally or not, it scares the living hell out of some conservatives.

A VAT is basically a national sales tax. To make sure that the government gets all the money it’s owed, the tax it’s levied on companies at each stage in the chain of production. So a hog farmer in Iowa would pay the VAT on the pigs it sells to Hormel; Hormel would pay it on the bacon it sells to Walmart; and Walmart would pay it on the bacon it sells to its customers. The important thing is that, in the end, the full cost of the tax gets passed along until it’s finally paid by consumers. While exotic to us Americans, VATs are commonplace around the globe. According to the accounting firm KPMG, 160 countries currently use a version of one; the United States is the only major developed nation the doesn’t.

Some economists like the VAT in concept because, as a consumption tax, it shouldn’t discourage saving or investment. Unlike a corporate income tax, it also doesn’t push companies to hide their profits offshore. But for Cruz—and for Rand Paul, who, while basically a nonentity in the race at this point, would similarly like to combine a VAT and flat income tax—the main appeal is that it could theoretically raise a lot of money to finance tax cuts elsewhere, which, in the scheme of his larger plan, would probably have the effect of shifting much of the nation’s remaining tax burden from high earners onto middle-class shoppers.3

How much could Cruz’s proposal net the government? The conservative-leaning Tax Foundation thinks $25.4 trillion over 10 years.3 Not enough to make up for all of Cruz’s cuts elsewhere, but not nothing either.

Cruz and Paul aren’t the first major Republican figures to embrace a VAT. Paul Ryan, for instance, actually included one in his 2010 budget plan. But the idea of a VAT has always made some conservatives deeply uncomfortable, because they worry that in the hands of a Democratic president, it could become a hidden money-making machine for the government. Passing a national sales tax would be hard, they say. But once it’s in place, slowly ratcheting it up to pay for additional spending would be relatively easy. “To be blunt, unless there’s a magic guarantee that principled conservatives such as Rand Paul and Ted Cruz (and their philosophical clones) would always hold the presidency, a VAT would be a very risky gamble,” Daniel Mitchell, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, wrote recently. His Cato colleague Chris Edwards frets that subbing out income taxes for a VAT would create “a mirage of cheap government.”

And they might sort of have a point. If you’ve ever been on a European vacation, you’ve probably noticed that your receipts have a little line for the VAT tax on each of your purchases. So the idea that the French and Italians are walking around blissfully unaware of the sales taxes they pay each day to fund their welfare state seems a little silly on its face. But Cruz’s plan in particular seems designed to be especially invisible to the public. Whereas most VATs function on something called a “credit invoice” system that helps make the fact that the VAT is a sales tax deeply obvious, Cruz’s borrows an approach from Japan called the “subtraction method,” which is a bit more oblique. In it, companies simply pay a levy on their total revenues minus the goods and services they buy from other companies (essentially, the government taxes the money that goes to salaries and profits). Economically, it works out the same as the invoice approach, but administratively it looks a little bit more like a regular corporate income tax, and it might make companies less likely to let shoppers know how much of their purchase is going to the government.

Of course, there would be nothing stopping Walmart from letting you know that 19 percent of the cost of your bacon is heading to Washington. My guess is that they would. But that still might not assuage worried conservatives, since most people don’t carefully track their receipts and would therefore have little idea of how much total tax they’d be paying. And, as a rule, Republicans like the process of paying taxes to be as excruciating and intrusive as possible so people will not only understand but resent how much of their paycheck they’re losing.

The ironic thing here is that Ted Cruz, anti-tax preacher, may be doing his best to craft a tax plan that leaves Americans in the dark about the actual cost of running their government. Simultaneously, he might be making political room for Democrats to start talking about a VAT tax of their own, since the subject is now fair game in Republican circles.

But, when push comes to shove, I’m pretty sure most on the right would be perfectly happy if the Cruz plan passed into law. A multitrillion-dollar tax cut is a multitrillion-dollar tax cut, after all.

1 Yes, I’m quoting the Tax Foundation’s static estimate on the low end. Its dynamic estimate, which factors in assumptions about tax cut-driven economic growth, says it would only add $768 billion to the deficit.

2 Cruz has pitched his plan as a 16 percent tax. That’s, at best, half-true. In his system, if you spent $119 on a very nice sweater, $19 of that would go towards the VAT. Most of us would think of that as a $19 sales tax on a $100 product. But because $19 is only 16 percent of $119, Cruz is citing the “tax-inclusive” rate of 16 percent. Which, I mean, come on.

3 For various reasons, it’s probably best to think of this as a high-end guess. Citizens for Tax Justice, which produced the $16.2 trillion cost estimate for Cruz’s plan, thinks his VAT would probably raise far less. If the public demands it, I might just write a post getting into why their estimates are so wildly different.

*Correction, Nov. 19, 2015: In the original version of this article, I stated that some economists like consumption taxes because they don’t discourage work (or saving and investment). That was wrong—as Harvard’s Greg Mankiw lays out in this old blog post, both consumption taxes and income taxes could, theoretically, dissuade people from working, since their earnings will still buy them less. (You can find a longer version of the argument from Robert Carroll and Alan Viard here). That said, the extent to which any taxes actually discourage labor is somewhat controversial.