Jeb Bush announced that he is running for president today. You know, officially. Not just in a dining room with some donors. He gave a big public speech and everything. And for a man who is supposed to be the sober, policy-minded establishment candidate, it didn’t take long before he detoured into economic nonsense:

So many challenges could be overcome if we just get this economy growing at full strength. There is not a reason in the world why we cannot grow at a rate of four percent a year.

And that will be my goal as president—four percent growth, and the 19 million new jobs that come with it.

See, the thing is, there are lots of reasons that the economy is probably not going to grow at 4 percent per year in the near future. The fact that Bush suggests otherwise doesn’t bode well for anybody hoping that his economic vision will be any more tethered to reality than his competitors’.

But before we get into all that, you may be wondering: Why 4 percent? “It’s a nice round number,” Bush explained to Reuters last month. “It’s double the growth that we are growing at. It’s not just an aspiration. It’s doable.” To get a little more specific, the figure apparently originated during a conference call several years ago, during which Bush and several other advisers were brainstorming potential economic programs for the George W. Bush Institute, the Texas think tank named for Jeb’s famously cerebral older brother. During the talk, Jeb casually tossed out the idea of 4 percent growth, which everybody loved, even though it was kind of arbitrary. The center now has a “4% Growth Project.” It does stuff like publish fact sheets about all the wonderful things that would happen to our country if we could ever manage 4 percent growth year after year.

To be fair, it’s not as if 4 percent growth is impossible, at least intermittently. The U.S. pulled it off a few times during the Reagan era and in the heat of the dot-com boom. The U.S. averaged 4.3 percent growth during most of its post–World War II economic expansions. But then the 21st century arrived. Between 2001 and the end of 2007, gross domestic product grew at an average rate of 2.8 percent per year. (Which makes the presence of a 4% Growth Project at the George W. Bush Institute more than a bit ironic, even if you forget that whole financial crash.) During the Obama years, the economy has expanded even more slowly.

And nobody really expects growth to rapidly shoot back up, at least unless we experience a technological revolution even more impressive than what the Internet delivered. Here’s why. In the end, potential economic growth boils down to a pretty basic formula. It’s productivity growth plus workforce growth. You can certainly break it down into smaller components if you want to get granular about things, but that’s the big picture: productivity plus labor supply. And right now, neither of those forces is working in America’s favor. Because the Baby Boomers are aging into retirement, the Bureau of Labor Statistics expects the labor force to grow by 0.5 percent per year in the near future, down from the 0.7 rate we enjoyed from 2002 to 2012. To simplify a bit1, that means productivity is going to have to jump up by 3.5 percent per year if we want to hit the magic 4.0.

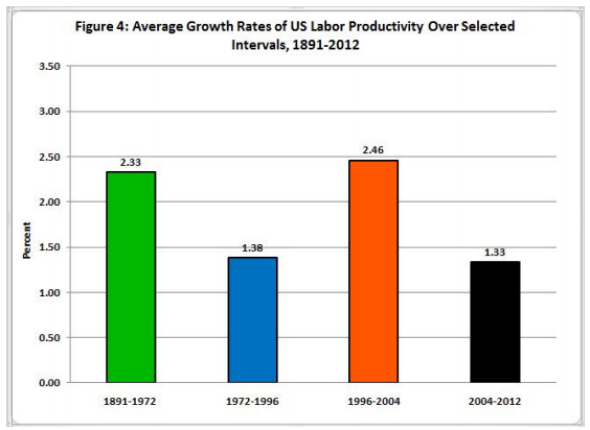

That just doesn’t really happen. Even during the prime years of the tech boom, workers only became about 2.5 percent more productive each year, on average. Unless artificial intelligence is about to catapult us into the Player Piano–esque future economists and tech types love to theorize about, it seems pretty unlikely that the United States is about to match that sort of progress in the coming years.

In Bush’s defense, he is willing to do certain things that would have salubrious effects on growth. Namely, he’s pro-immigration reform. If nothing else, bringing more young workers into the country would help boost our labor supply. But any reform that Bush could realistically achieve with a (presumably) Republican Congress isn’t going to increase our annual immigration flows enough to overcome the demographic headwinds we’re facing today.

So Bush is too optimistic about our economic prospects. What’s the big deal? My guess is that the overconfidence will be baked into his policy proposals. Don’t be surprised to see white papers promising that with the right mix of tax cuts, deregulation, and tweaks to immigration, we’ll suddenly be riding high on a new period of growth, which will allow for all sorts of heroic predictions about tax revenue and the future of the deficit. Sober and serious won’t be on the menu.

1Slightly more nuanced version: Economic growth = increase in output per hour of work (aka productivity growth) x increase in total hours worked. So, theoretically, even if we’re not adding a lot more workers to the economy, growth could rise quickly if everybody started pulling longer hours on the job. But as Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon has noted, hours per worker have typically been on the decline in recent decades.