Over the weekend, the New York Times managed to publish one of the most confused op-eds on the price of higher education that I’ve ever had the displeasure of reading. Paul Campos, a law professor at the University of Colorado, would like us all to believe that college deans who say they have to raise tuition because of government funding cuts are just fibbing. “In fact, public investment in higher education in America is vastly larger today, in inflation-adjusted dollars, than it was during the supposed golden age of public funding in the 1960s,” he writes. According to Campos, the idea that a degree costs more because states have pulled back their help “flies directly in the face of the facts.”

Not really. There are a great number of complicated, interlocking reasons that a bachelor’s degree costs so much more today than it used to. And dwindling government subsidies are one of the key issues.

Overall, public spending on higher education has, as Campos argues, risen dramatically over the long term. But so have the number of Americans attending college. When administrators say that government support is shrinking, what they usually mean is that per student appropriations have fallen. This is a crucial point. Someone has to foot the bill for each and every undergraduate’s education. If taxpayers don’t do it, then families have to pick up the slack themselves.

Campos halfway understands this. “While state legislative appropriations for higher education have risen much faster than inflation, total state appropriations per student are somewhat lower than they were at their peak in 1990,” the professor writes. But he attempts to scoot around that fact with a rather poorly constructed analogy.

It is disingenuous to call a large increase in public spending a “cut,” as some university administrators do, because a huge programmatic expansion features somewhat lower per capita subsidies. Suppose that since 1990 the government had doubled the number of military bases, while spending slightly less per base. A claim that funding for military bases was down, even though in fact such funding had nearly doubled, would properly be met with derision.

The military base comparison is weak for a couple of reasons. First, it obscures more than it reveals. We worry about per-student funding in higher ed because students pay tuition. Service members, of course, do not pay tuition, though they do draw a salary and would probably be quite unhappy were their paychecks slashed. If that happened, some might reasonably be tempted to accuse the Pentagon of cutting service member compensation, even while defense spending rose overall. Likewise, it’s fair to worry about declining student subsidies, even while total education spending heads higher. But Campos’ point fails on a more basic level, too. If the U.S. government wanted to run its military bases using slightly fewer personnel to save money, it might be able to do so. Sadly, nobody has yet figured out a way to run a university using drastically fewer professors without sacrificing some educational quality (and no, the Internet has not changed that). While schools have managed to restrain their spending by paying masses of part-time adjunct faculty a pittance, the cost of instruction is still going up. Until someone comes up with a brilliant strategy for making teaching a more efficient endeavor, the fact that states provide colleges with a smaller sum of cash per student than they did 25 years ago will mean that, for all intents and purposes, education subsidies have been cut. Academia is simply not prepared to do more with less.*

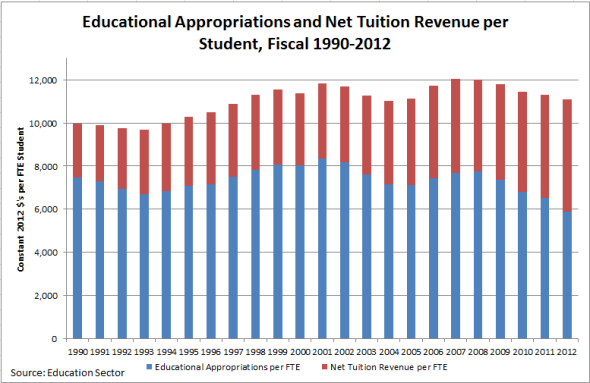

To his credit, Campos is at least gesturing towards an important point. Even in years when states increased their per-student education spending, public colleges still raised their prices faster than inflation. And while schools tend to up tuition when legislators cut their budgets, they don’t usually lower it when the subsidies get restored (see the graph below1). Instead, they lock in the extra revenue so that they can spend more per undergrad. Where has that money gone? Here, Campos is more on point. As he writes, universities are spending an increasing share of their budgets on administration. In other words, the bloat really has grown in higher ed, and it’s costing students.

But that doesn’t change the fact that government cutbacks have contributed to the problem. There have been moments when university profligacy has been the major driver of tuition increases. At others, contracting state support has played a critical role. This has especially been the case in these days of post-recession budget austerity. Depending on who’s calculating, states are giving schools somewhere around 25 to 30 percent fewer dollars per student than they were 15 years ago. And someone has had to make up the difference. Namely, college kids.

1You might notice that, contra Campos’ article, the graph I’ve included shows per-student subsidies peaking in 2001, not 1990. I’m not really sure where he got that 1990 was the high point. I’m using a graph by Education Sector that adjusts for inflation using the Consumer Price Index. Some people rely on numbers from the State Higher Education Executive Officers, which use a idiosyncratic inflation index specifically designed for universities, but they also put the peak at 2001. The College Board reaches a little further back and puts the high point in the mid 1980s.

*Update, April 6, 2015, 12:42 p.m.: I updated this paragraph to better spell out why Campos’ military analogy doesn’t really work. Frankly, the original version was also too glib.