Uber is famously unafraid of clashing with government regulators. But it might just be terrified of taking on its own drivers.

While Uber has brashly forged ahead with its ride-sharing service in the face of stiff opposition from German authorities (not to mention other protests across Europe), the company on Friday abruptly backed down from recent policy changes that had stirred protests and strikes among as many as 1,000 drivers in New York City. Uber infuriated workers on Labor Day when it said that drivers of its higher-end “Black” and “SUV” services would be sent UberX and UberXL fares as well. “Starting now, all BLACK and SUV partners will automatically receive uberX / uberXL requests,” the company wrote in an email on Sept. 1. Some drivers chose to decline those requests; over the next two weeks, they were told by Uber that declining too many rides could risk deactivating their accounts.

[Update, Sept. 12, 2 p.m.: Here’s a bit more background on these various tiers of Uber service. UberX and UberXL are the cheapest services Uber offers in New York City, billed as “the low cost Uber” and “low-cost rides for groups,” respectively. The fare minimum for UberX rides is $8 and it’s $12 on UberXL, while rides on UberBlack and UberSUV—the company’s higher-end car services—start at $15 and $25. The more upscale services also have higher base fares and charge riders more per minute and per mile.]

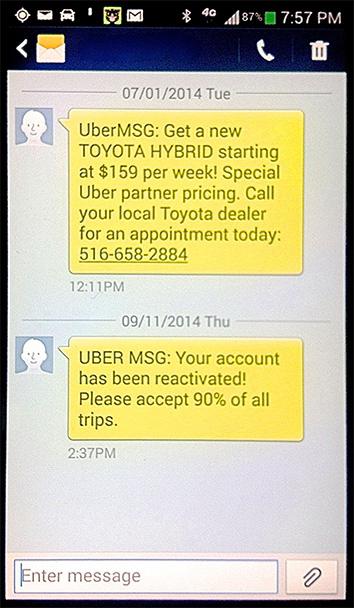

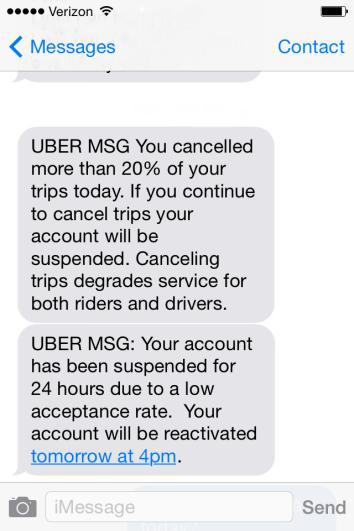

Chakib Seddiki, an Uber SUV driver who has worked with the company in New York for two and a half years, said he knows several people who had their accounts shut down for 24-hour periods over the last week after they declined too many UberX requests. Seddiki’s own account was deactivated from 4 p.m. on Monday until 4 p.m. on Tuesday, and he was told that if his ride acceptance rate fell below 90 percent it would be turned off again. Ifram Chaudri, an Uber SUV driver of eight months, said Uber shut down his account from Wednesday afternoon until Thursday afternoon for a similar reason. Chaudri and Seddiki provided Slate with the messages that Uber sent them upon deactivating and reactivating their accounts:

Photo by Abi Diaz.

Screenshot.

Late on Friday morning, Uber abruptly backtracked. “Effective immediately, UberBLACK and UberSUV partners can choose when and where to receive UberX requests,” the company wrote in an email blast sent to drivers. Further down in the message, it showed an option on the Uber app that allows drivers to switch between accepting UberX rides and limiting requests to only Black and SUV customers. When asked for comment, Uber pointed to that email.

Drivers say Uber’s brief decision to make them accept UberX fares was the latest in a string of shifts that have made working for the company steadily less profitable. Over the summer, Uber slashed fares on UberX by 20 percent to make it “cheaper than a New York City taxi.” At the same time, it has increased the share it takes from drivers. Uber now collects 20 percent of UberX fares (up from 10 percent), 25 percent on Uber Black fares (up from 20 percent), and the same 28 percent on Uber SUV fares.

Uber defends its price cuts and push for drivers to use UberX by arguing that servicing more frequent, albeit cheaper, fares actually leads to increased income for drivers. “[U]berX demand has grown dramatically over the last year, to the point where uberX partners have actually been earning MORE per hour than UberBLACK drivers, after all deductions and expenses,” a company representative wrote in an email to Seddiki. “To address this and help boost BLACK and SUV partner earnings, we allowed partners to opt-in to accepting uberX/XL trips over the summer. The results were dramatic: drivers who accepted X and XL trips earned 35-50% more per hour on average than those who did not. While partners sometimes had slightly higher gas and operating costs from doing more trips, our summer test showed that drivers’ increased earnings more than covered this cost.”

Seddiki contests this math. His own experience shows that it takes, on average, 10 minutes to drive to get an UberX fare and then another five to 10 minutes for that person to come out for the ride. From there, it takes about 10 minutes to complete the usually short rides UberX passengers take. Altogether, that’s 30 minutes for which Seddiki typically gets the $8 minimum. Uber’s 20 percent commission deducts $1.60 and sales tax and black car fees take out another $0.80. Because Uber drivers are contractors and not employees, they also have to cover any expenses they incur while working. For half an hour of driving, Seddiki expects his SUV to consume about $2 worth of gas—much more than the hybrid vehicles used by most UberX drivers will eat up in the same period. “That means before car depreciation and insurance, I end up with $3.60 from $8,” he says. “If we look at it by the hour, that will be $7.20.”

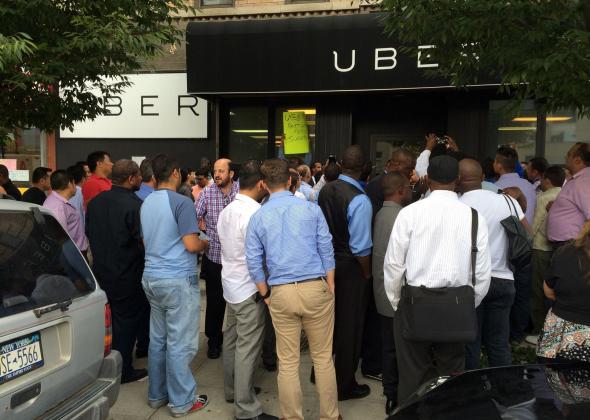

Protests against Uber over wages have already broken out in other parts of the country. On Sept. 2, around 50 Los Angeles–based Uber drivers gathered in a North Hollywood parking lot to rail against recent fare cuts. Earlier this week, 200 drivers assembled outside Uber’s office in Santa Monica to further protest the pay cuts and their treatment by the company. Uber has also been hit with several class actions over its practice of including tips in the commission it collects from drivers. By conceding to drivers on the UberX policy—admittedly a rare step for Uber to take—the company is likely preventing days of bad press and protests that could draw consumers attention to the unrest and accusations of bad labor practices.

Despite Uber’s reversal, organizers said on the Uber Drivers Network NYC Facebook page that the strikes planned for Friday will continue and that a meeting scheduled for 4 p.m. in Queens will still take place. “This is a victory for us,” the network posted on its page. “However our fight MUST continue, because we’ve won a battle but the war is not over.”

Uber is of course interested in keeping rates low to provide its customers with the cheapest fares and most efficient service possible. But riders are only one half of Uber’s platform. And in a market brimming with competition, aggravated drivers have other companies they can choose to work with. Already, Chaudri and Seddiki say they have seen colleagues abandon Uber for its main competitor, Lyft. “In the beginning Uber was very nice with us. Now when you go to the office they treat you like a slave,” says Chaudri, who has also started taking rides for Lyft’s platform. “When Lyft asked me if I had any questions, I said only one: You will be smiley and nice with us all the time or just for a few months, like Uber?”