Conservatives like to argue that if we trim the social safety net, private charities will step in and tend to the needy. Paul Ryan—he of the soup kitchen photo-op—especially loves to extol the virtues of volunteers and philanthropy.

So I was pleased to see this new piece in Democracy by Roosevelt Institute fellow and Rortybomb blogger Mike Konczal, who lays out precisely why private giving has never been able to fully substitute for government aid in the U.S.—and why it never will. Konczal makes a nuanced, multilayered argument, and I want to draw attention to one particular aspect of it. The problem with charity is that, unlike government programs, it is most likely to fail when the poor need it most: during recessions.

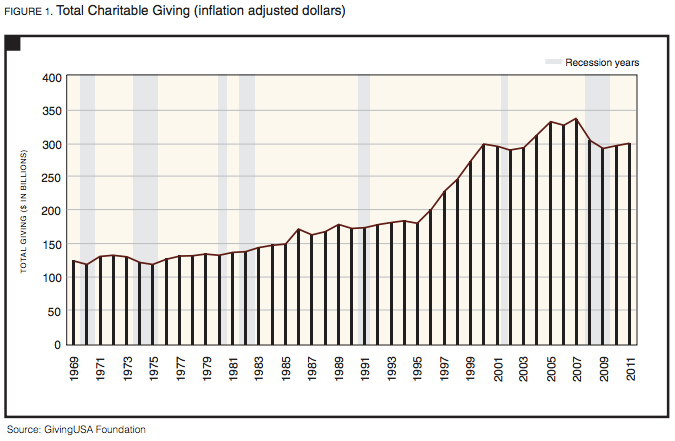

Consider our last economic meltdown. Stanford University’s Rob Reich and Christopher Wimer found that in 2008, charitable giving fell 7 percent (as shown in their graph below). It dropped another 6.2 percent in 2009, as Americans flooded the unemployment rolls. Donors did seem to target more of their money to the poor; giving to food banks, for instance, rose 31.9 percent in 2009, to about $1.6 billion. But even that money was only a tiny fraction of the support provided by food stamps, which automatically surged as the job market withered.

That is the key difference between government and charity: Where private giving might dry up in a particularly nasty recession, federal safety net programs like unemployment insurance and food stamps act as what economists call “automatic stabilizers,” meaning the worse the economy gets, the more money they pump out. Konczal writes:

During 2009, while private charity collapsed, automatic stabilizers expanded rapidly, from 0.1 percent of GDP to 2.2 percent of GDP—or a number roughly akin to all charitable giving in the United States. This was directly targeted at areas that suffered from the most unemployment, and helped those most in need—efforts that, as we’ve seen, private charity does only partially. As Goldman Sachs economists concluded, this shift made a crucial difference, and, alongside the government’s efforts to prevent the collapse of the banking sector and the Federal Reserve’s expansion of monetary policy, was a core reason the Great Recession didn’t become a second Great Depression.

Would Americans have given more if they knew the safety net wasn’t there to catch the jobless? Perhaps. But, as Konczal writes, the Great Depression already demonstrated that private charity isn’t a reliable backstop in a true crisis. Before the New Deal and the modern welfare state, Americans relied much more heavily upon volunteer groups, fraternal societies, and other sorts of private aid (government played some role too). The help these organizations provided could be spotty, but it was better than nothing. Then came the crash. Again, per Konczal:

Informal networks of local support, from churches to ethnic affiliations, were all overrun in the Great Depression. Ethnic benefit societies, building and loan associations, fraternal insurance policies, bank accounts, and credit arrangements all had major failure rates. All of the fraternal insurance societies that had served as anchors of their communities in the 1920s either collapsed or had to pull back on their services due to high demand and dwindling resources. Beyond the fact that insurance wasn’t available, this had major implications for spending, as moneylending as well as benefits for sickness and injuries were reduced.

In short, when conservatives imagine their utopia of less government and more charity, they’re picturing a movie we’ve seen before. And it has a very gruesome ending.