What if George Zimmerman had been poor? What if his legal case hadn’t attracted national attention and raised over $300,000?

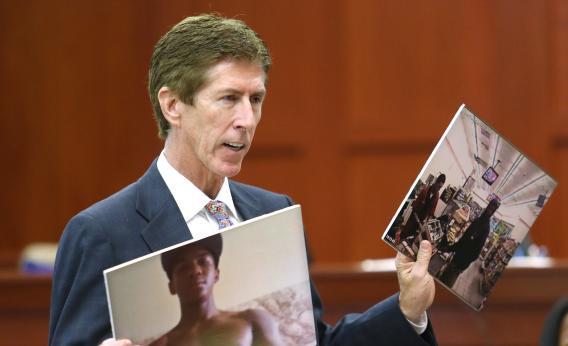

In the wake of Trayvon Martin’s death and Zimmerman’s non-arrest and then arrest and then trial and aquittal most of the counterfactual scenarios I’ve seen have dealt with race. Zimmerman’s attorney Mark O’Mara says Zimmerman would never have been arrested had he been black, in which case the race angle never would have led to national pressure on the local police to second-guess their initial decision to believe his story. Others have raised the question of whether a young black man who shot and killed the only eyewitness to a fistfight he provoked would ever have gotten the benefit of the doubt from a white jury and I think the answer is no.

But looking back at it I do think the best question to ask is what if Zimmerman hadn’t had the resources to hire O’Mara in the first place? What if Zimmerman, like most criminal defendants in the United States, was relying on a public defender with little emotional or financial investment in winning the case and no resources with which to pursue a robust defense even if he’d been inclined to do so. Wouldn’t that defender have told Zimmerman that the smart way to avoid a second-degree murder sentence was to plead guilty to manslaughter and work out terms of incarceration that would be less onerous than what he’d end up with if he fought and lost. And of course the last thing any sensible person wants to do is go to trial with his entire life on the line in a situation where his own attorney has just plainly said he’s not enthusiastic about running the case.

And in this instance, maybe that would have meant justice would be done. But it’s a disturbing reality of the criminal justice system in the United States. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is a very difficult evidentiary burden to meet if the state is facing off against a competent, well-financed, and highly motivated defense team. But all these people sitting in America’s prisons—and there are an awful lot of them—aren’t losing at trial. Instead 97 percent of federal cases and 94 percent of state ones end in plea bargains. People ask me sometimes why nobody’s gone to jail for crimes related to the financial crisis. It’s a complicated question, but obviously part of the answer is that you’re not going to resolve a criminal fraud case against a multi-millionaire by railroading him into a plea agreement. O’Mara and his team are much more capable and expensive than your typical criminal defendant can afford, but they’re a joke compared to what a truly rich person would throw into a case. Up against the big fish, it’s the prosecutors who’d be outgunned and outresourced and forced to ask themselves if it’s really worth the time and energy when there’s a deal on the table. It’s much more cost-effective to punch down and prosecute the guys you can beat.

For better or for worse, Zimmerman got his full day in court. The weaknesses in the prosecution’s case were thoroughly probed and the real meaning of the burden of proof was tested. Most people don’t get that. Could Zimmerman have possibly won with the public defender? Would he have even gotten a trial? And what kind of country makes the size of the checks you can cut the difference between going free and going to jail?