About 15 years ago, an independent bookseller in Texas went to battle against the specter of mega-bookstore invasion. His weapon of choice was something a purveyor of books knew best: a word. And the word was weird.

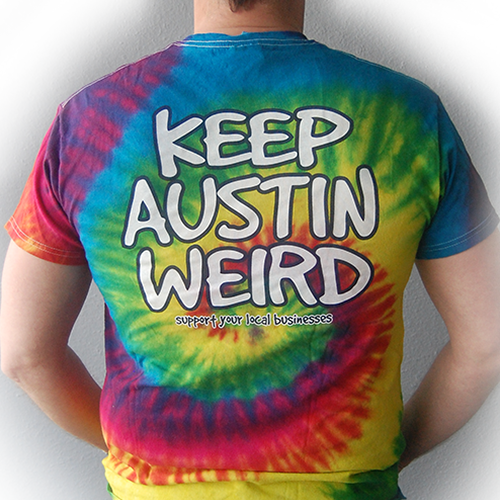

KEEP AUSTIN WEIRD was coined by the librarian Red Wassenich while on the phone with a local radio station. But the phrase was adopted when Steve Bercu, owner of the Austin, Texas, bookstore Book People, needed a slogan to rally objection to a planned Borders store a few blocks away. Bercu convinced John Kunz, the owner of nearby Waterloo Records, to join the keep-it-local cause. They printed 5,000 bumper stickers urging citizens to KEEP AUSTIN WEIRD and flanked the message with their business logos. The stickers flew off the shelves. And the Borders bookstore was never built in downtown Austin.

“WEIRD resonated really well here,” said Bercu. “The point was to support local businesses. Everyone got it immediately.” Today, Bercu estimates that he’s given away more than 300,000 stickers. Indeed, the success of KEEP AUSTIN WEIRD inspired independent business communities from Oregon to California and beyond. Why has weird spread so far?

Terry Currier, the owner of Portland, Oregon’s Music Millennium store, was a frequent visitor to Austin and a longtime friend of Kunz’s. As he worried about the future of his city, the weird war in Austin struck a chord. “I wanted some kind of campaign to champion local businesses,” said Currier. “Portland has always been an entrepreneur’s town with a lot of open-minded and creative people.”

He started off with 1,000 KEEP PORTLAND WEIRD bumper stickers and ran a newspaper ad with a simple image of the sticker—no business logo, no explanatory message. “Then the thing just kept growing and growing, to the point where news commentators used the motto and it showed up in the papers and pictures,” he said. Now it’s entrenched in the local culture and immortalized in Portlandia.

Seven hundred plus miles to the south—and just a little left—Bookshop Santa Cruz owner Neal Coonerty printed KEEP SANTA CRUZ WEIRD stickers after meeting Bercu at a booksellers’ conference. “We don’t want to become just another gentrified suburb of Silicon Valley,” said Coonerty. “The main street of our downtown is more than just an exchange of goods, it’s where the community expresses itself with street artists, political tabling, and one-of-a-kind parades. We want to make sure it stays that way.”

Not everyone wants to be weird, though. Santa Cruz city supervisor Ryan Coonerty, Neal’s son, says he regularly hears complaints that promoting weird is akin to encouraging criminal or antisocial activity. Some local business owners prefer to be known as “safe and sane.”

Across the river from the weirdness in Portland, the locals have lobbied to KEEP VANCOUVER NORMAL. In the flatlands of West Texas there’s a call to KEEP ABILENE BORING. Just north of Austin, the Dell Computer headquarters wants to KEEP ROUND ROCK MILDLY UNUSUAL. On the other hand, in the home of two infamous shootouts, natives recognize their destiny is to KEEP WACO WACKO. And there’s a KEEP IT QUERQUE crusade in New Mexico.

Weird campaigns have spread to communities in more than a dozen states. What do they all have in common? The cities have fewer than 1 million people, but most are growing. Many are state capitals or county seats and most have a vibrant arts scene. They all seem to have a strong sense of what makes them unique, and a grassroots urge to stay that way.

That cities cast their lot with weird has an uncanny connection back to the word’s origin. The Old English wyrd has roots in the base wer (meaning “to become” or “to turn”) and was once connected to the idea of destiny. In Norse mythology, Wyrd (Urðr) is one of the three female fates who shape the lives of every child. But wyrd was going extinct when Shakespeare cast the Three Wyrd Sisters in the role of the fates who prophesied that Macbeth would murder Scotland’s king. To provide context for audiences unfamiliar with the word, the Bard created “double, double toil and trouble” sorts of activities for the sisters; that link to the supernatural followed wyrd thereafter.

Poets like Shelley and Keats reinterpreted weird to describe the odd or strange. And then weird went into hibernation through much of the 20th century, until popular culture revived it yet again. In the 1980s, the likes of “Weird Al” Yankovic and the movie Weird Science imbued the word with a quirkier, goofier meaning. Mark Moran and Mark Sceurman have tracked weirdness for 20 years, with published guides to weird attractions and a History Channel series called Weird U.S.

Despite its countercultural bona fides, weird has economic power. From indie booksellers to microbrews and real estate, leveraging quirkiness is good for business. Weird isn’t just a way of being, it’s an economic strategy, one that has the rough-hewn, indie-rock air of an anti-strategy. Marketing specialist Seth Godin promotes weirdness as a way to celebrate choice and push back against mass production and consumption in his book We Are All Weird. “The opportunity of our time is to support the weird, to sell to the weird and, if you wish, to become weird,” he writes.

Underneath it all, the affinity for weirdness harkens back to the oldest origins of wyrd, which conjured mastery over the fates. From booksellers in Austin to hippies in Portland to squares in Abilene, we all want to control our own destinies. Is that so weird?