Since March, Facebook has been testing software in the United States designed to detect when users may be at risk of hurting themselves, so that its trained human specialists can then intervene and offer them help. The company announced Monday that it’s expanding that effort and taking it worldwide.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg is already presenting the program as a big win for the machines. “Here’s a good use of AI: helping prevent suicide,” he wrote Monday in a post on his Facebook page. Zuckerberg continued:

Starting today we’re upgrading our AI tools to identify when someone is expressing thoughts about suicide on Facebook so we can help get them the support they need quickly. In the last month alone, these AI tools have helped us connect with first responders quickly more than 100 times.

With all the fear about how AI may be harmful in the future, it’s good to remind ourselves how AI is actually helping save people’s lives today.

Press coverage of the news echoed this reverent tone. “This is software to save lives,” begins TechCrunch’s post, which appears to have been published even before Zuckerberg’s. “Facebook’s new ‘proactive detection’ artificial intelligence technology will scan all posts for patterns of suicidal thoughts, and when necessary send mental health resources to the user at risk or their friends, or contact local first-responders.”

To the extent the project really is saving lives, that’s certainly worth celebrating. But without credible research into how well it’s working, the victory lap feels unearned. And Zuckerberg doesn’t help by framing the project more as an image-booster for A.I. than as a humble attempt to grapple with a complex and deadly problem.

This is not to disparage Facebook’s approach or its intentions. It’s good to see the company taking on a project that appears motivated more by a desire to look out for its users than to bolster its bottom line. Facebook notes that it developed its methods in partnership with third-party experts and help lines, which suggests it’s not just making things up as it goes along (historically, a common pitfall in Menlo Park).

The company’s reputation for capitalizing on every morsel of data means that even its life-saving efforts are bound to draw alarmed responses from some quarters. But at this point there’s no reason to suspect a larger or more nefarious plan at work here. If you want a cynical take, suffice it to say that the company understands it’s not in its best interest to have people broadcasting their own suicides on Facebook Live. This, sadly, is not a hypothetical problem.

In any case, the technology here sounds rather less impressive (or worrisome) than one might expect from the headlines about “A.I..” Facebook says it’s using “pattern recognition” to help identify posts and live streams that might be “expressing thoughts of suicide.” So what patterns is the software recognizing? All Facebook has said so far is that it picks up on signals in the text of post and comments: “For example,” it explains, “comments like ‘Are you ok?’ and ‘Can I help?’ can be strong indicators.” Perhaps there’s more to it than that that the company isn’t disclosing. But technically, it sounds like pretty basic stuff—hardly Minority Report-style intelligence.

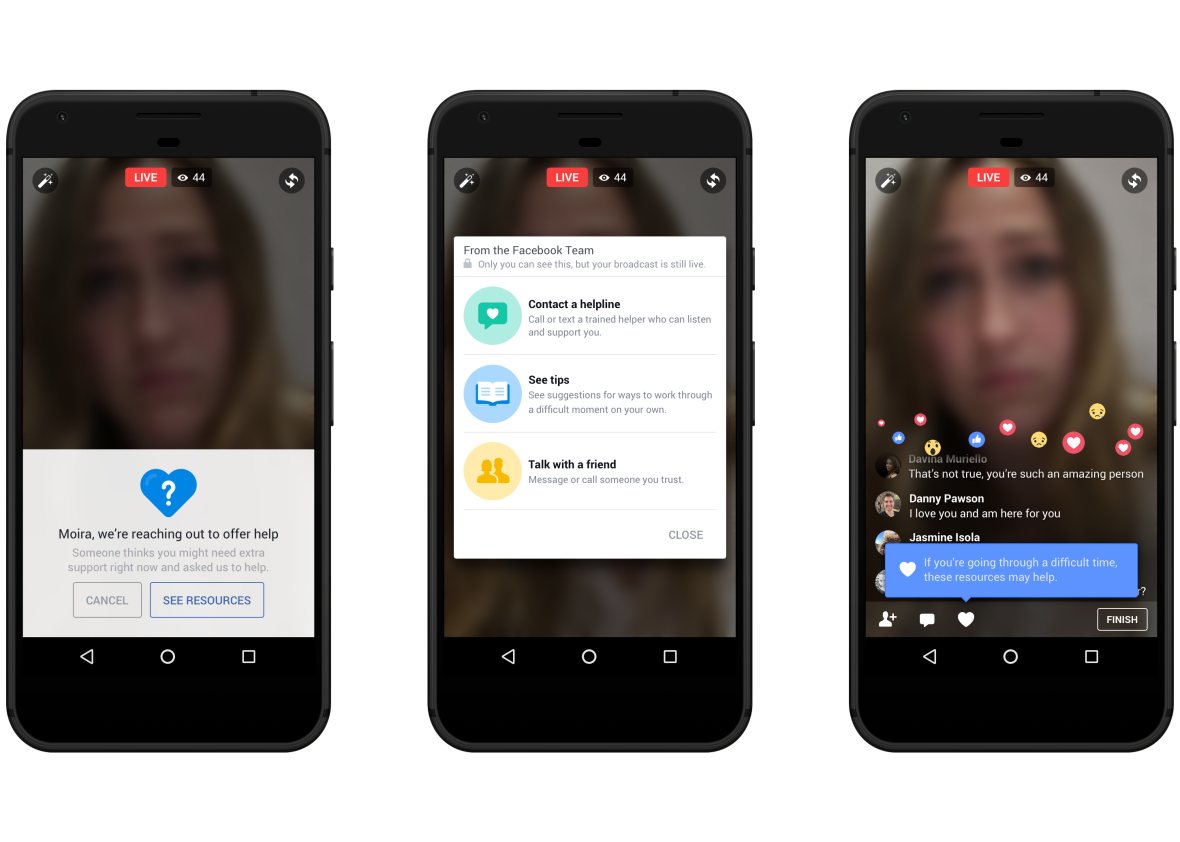

That’s OK in a case like this, because Facebook doesn’t need the A.I. to identify people at risk with anything close to perfect accuracy. All it needs the software to do is flag posts (and live streams) that might indicate there’s a problem. At that point, Facebook’s trained human employees can investigate and see whether there’s cause for real concern. This is the same process that Facebook was already using when its users manually flagged someone’s post as worrisome. In other words, the A.I. is just generating leads, not making the actual call as to whether an intervention is warranted. It’s probably especially useful in cases such as live-streaming, where the speed of the intervention could mean the difference between life and death.

The clear human oversight is reassuring, insofar as “A.I.” tends to go wrong when it takes a lead role rather than a supporting one. But it’s a little disingenuous for Zuckerberg to imply that it should assuage our fears about the potential downsides of artificial intelligence, either now or in the future. Of course machine-learning software can be put to noble uses. It’s the harm it can do when misused that worries people.

Zuckerberg’s crowing feels especially empty given that Facebook provides relatively little support for the claim that the program is, in fact, saving lives—aside from the single anecdote in the video above, which is genuinely heartwarming.

Intervening with mental health resources when someone is seriously considering suicide is obviously a worthy endeavor, provided it’s done thoughtfully. Its success, however, depends on how well-targeted, well-timed, and effective those interventions prove to be. So far, Facebook hasn’t really told us those things. Perhaps it will, in some forthcoming study—but the company has a poor track record when it comes to sharing data with independent researchers. (Of course, there are legitimate privacy concerns when it comes to information about people’s mental health.)

It’s great that Facebook has connected more than 100 users with first responders in the past month, as Zuckerberg writes. And saving even a few people who would have otherwise committed suicide would redeem a lot of flaws. Still, if it’s aiming most of its interventions at the wrong people—or even, potentially, the right people at the wrong time—they might not be as beneficial as one would hope. At worst, they could be mostly clogging crisis hotlines and diverting resources from others who need them more.

It’s good to see Facebook putting some of its technology to use for the wellbeing of its users. It’s just that it would be easier to congratulate the company if it didn’t seem to be in quite such a hurry to congratulate itself.