Stephen Lam/Getty Images

Apple wants everyone to have their heads lodged in their own personal clouds.

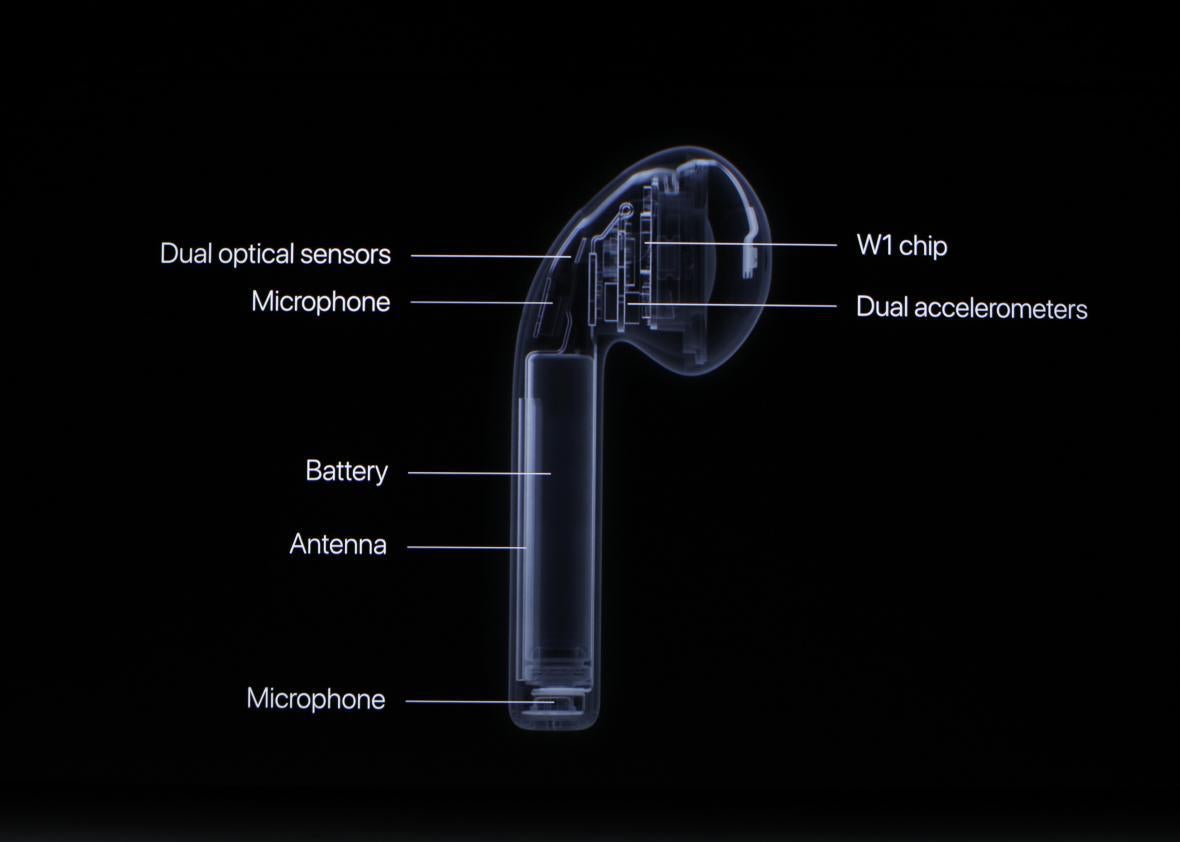

From the wireless AirPod headphones the company released last year to the iPhone and the Watch, Apple has been building wearable and pocket-size products that, when networked together, turn each user into a kind of internet of one, with various devices that patch into the user’s own cloud. Think of it like a mini-intranet that walks around with you: your phone talking to your watch, which is sending information to the small pods in your ears, all tethered to the same storage vault. On Tuesday, at its annual product rollout in Cupertino, California, Apple is expected to unveil even more ways to bring information into your cloud.

The Apple Watch, according to Bloomberg, will get an update that allows it to connect directly to cellular networks without needing to be tethered to an iPhone. And a new iPhone is expected to include wireless charging capabilities.

Between the AirPods and iPhone and Watch, one can listen to a favorite podcast, count their steps and heart rate, send reminders, participate in meetings, play games, read the news, tweet, and text, all while leaving their hands free to do other things. These devices share data between each other—linked to the user’s account in iCloud, which stores photos, documents, and other information that can be summoned down to any appropriate Apple-compatible device as needed. It suggests a future of completely cloud-based personal computing, where no matter what device you’re using—TV, laptop, smartwatch, tablet, iphone—you can always pick something up right where you left off.

It’s a relief, if anything, for those of us who remember the days of forgetting our USB drives or emailing documents to ourselves or starting the day off on the wrong foot because we forgot to download music to our mp3 player or phones. It’s also not a huge leap from how many of us use, say, Google Docs now. But something about being stuck in your own personal cloud—or to be more precise, the cloud Apple is lending you a slice of—is also alienating.

Who hasn’t walked down the street with headphones on, staring at their phone or smartwatch, completely tuned out? Cloistered in our own personal media environment, where all our preferences are at our fingertips, we no longer notice the couple having a fight on the corner or the kid barreling down the sidewalk on a tricycle. Of course, we’re also tuning out catcalls and cars honking, and I’ll admit that’s something I love about getting stuck in my personal cloud.

Yet I still find myself—as hyper-connected to my friends and my own tastes as I’ve ever been—alone. And not just alone, but alone with Apple, a company I’m expected to trust by dint of its success or superior design or relatable ads—or just because I feel I really don’t have a choice. Sure, Apple has defended user privacy, like when it pushed back against the FBI’s demand to unlock a phone tied to a suspect in the San Bernardino, California, terrorist investigations, and its CEO has spoken out against President Trump’s anti-immigrant and transphobic policies. But Apple is also the company that has more than $100 billion stashed in offshore accounts that it doesn’t want to pay taxes on. And it’s the company that deleted more than 60 apps from its App Store in China last month, bowing to Chinese censors. (These apps were Virtual Private Networks, or VPNs, a type of service that allows users to route around China’s internet filters that block people from accessing foreign news and social media, as well as information about democracy activism or dissent in the country.) And its flagship iPhone has for years been assembled at Foxconn plants in Shenzhen, where in 2010 workers were so unhappy that they started killing themselves. When we choose to have that intimate relationship with a company, as Apple’s increasingly interwoven products demand that we do, we need to remind ourselves of its baggage, too.

It certainly is exciting to consider the possibilities of my own personal cloud, my internet of one, with my favorite podcasts and health data and friends on social networks in my ears and at my fingertips in a kind of aurora of data that follows me wherever I go. But we’ll all have to remember to look up once in a while, to take out our AirPods and hop off our clouds. If we don’t we might forget that all the data swirling around us isn’t necessarily our own; it’s held at a private company that’s making more money than any other company in the world. And what is actually ours, our experiences and memories and connections with friends and neighbors, might escape us.

Tom Gruber, one of the co-inventors of Apple’s Siri said at Ted this year that one day he’s certain that artificial intelligence will be used to upload and access our memories. If that’s a direction Apple wants to go in—storing our most intimate and haunting thoughts in its cloud—then perhaps now is the time, before the inertia of technological progress simply takes us there, to think deeply about whether having a personal cloud that follows us everywhere we go is actually a future we want.