This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. On Thursday, Dec. 3, Future Tense will host “Afrofuturism: Imagining the Future of Black Identity” in New York. For more information and to RSVP, visit the New America website.

Humans have always been interested in the nature of the universe. In 1977, NASA advanced that interest when it launched Voyager 1, the first human-made object to enter interstellar space and gather plasma wave data. This data has been converted into sounds, and more recently, into geometric figures depicting the cosmos such as time and space. Motivated by the first black president’s call for Americans to enter orbit around Mars by 2030, black artists—like me—have been inspired to explore these phenomena. Some of these works are in keeping with Afrofuturism, an emerging cultural practice that navigates past, present, and future simultaneously. A theme I’ve explored through Afrofuturism is navigation, or ascertaining one’s position in the world and following a route toward the future. This journeying has led me to discover new conventions of data representation, access, and art through digital technologies.

Image courtesy the author

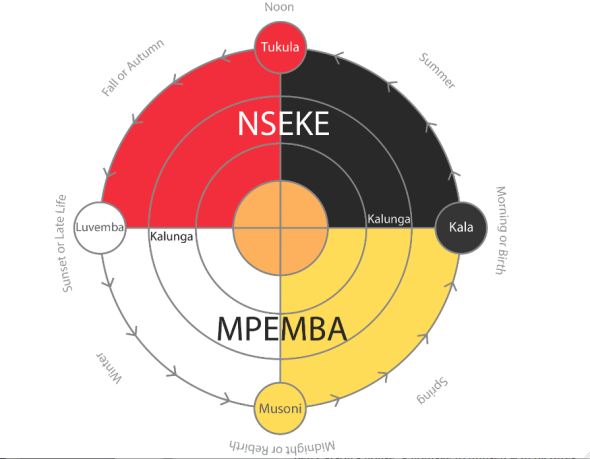

Humans have also always been interested in making maps of their world, and these maps, like star charts, suggest a way of navigating space. The cosmogram—a cultural map of the universe—centralizes practitioners in specific rituals. The Kongo cosmogram emerged as a point of contact and communication between worlds. Cosmograms such as Haitian veve or the sacred ground drawings of Umbanda called pontos riscados have a foundation in African cosmology, indicating a connection to the spirituality of African representational space. As a cultural or ritualistic device, the cosmogram drives the Coltrane Matrix, which musicians use to create jazz harmonies; the drawing John Coltrane created for 1960’s Giant Steps; and similar designs such as mandalas found in other cultures around the world. Jean Michel-Basquiat’s 1983 painting King Alphonso also features a cosmogram.

Image courtesy the author.

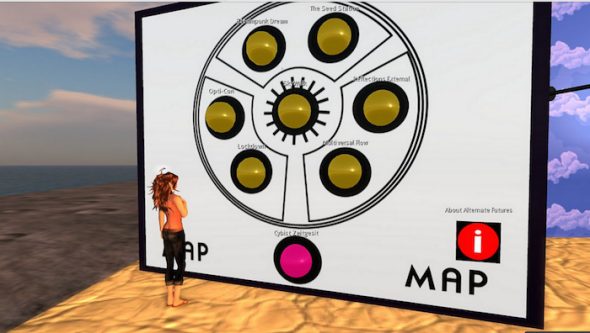

From 2006 until 2010, IBM was heavily invested in Second Life as a platform to replace face-to-face telecommunications. The IBM Exhibition Space granted artist residencies in Second Life to simulate different types of creative production. This included my 2010 exhibition Alternate Futures: Afrofuturist Multiverses & Beyond, which presented several virtual 3-D simulations and themes. What prompted this show was my growing interest in Afrofuturism. Cultural artifacts such as the cosmogram were used as navigational guides to help visitors get to different parts of the IBM Second Life exhibition. The guide was an interactive map with embedded content, as well as buttons programmed with coordinates to the installations. Sound was an important part of the IBM SL exhibition, especially afrofuturistic, electro-funk music such as Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew (1970) and Funkadelic’s Cosmic Slop (1973). I created a cosmogramlike scepter with a spinning Eye of Horus, an ancient Egyptian symbol of protection, above which towered Sun Ra, the late black American jazz composer, musician, and proto-Afrofuturist.

Sun Ra was among the very first to own something called the Outer Space Visual Communicator that enabled his music to be turned into colors reflected on a wall, creating a kind of synesthetic effect. I’m interested exploring how creative expression with computers can take what Ra was doing in the 1970s to the next level. I used Linden Scripting Language to give behavior to objects such as the interactivity in the Alternate Futures cosmogram maps. I use open graphics language to generate dynamic music visualizations based on NASA plasma wave data and sound conversions, jazz and electronic music with interstellar space themes. These works are based on two-dimensional cosmogram-based designs that visually express how pioneers such as Sun Ra breathed life into his music. I use small computers called microcontrollers and sensors that can be sewn into fabric or embedded in physical objects. These microcontrollers connect to sensors that respond to sound, light, and movement.

What I call Afrofuturism 3.0 or the coming wave of this movement is grounded in cyberpunk or postmodern sci-fi, DIY culture, electronic music, and data visualization. This includes deeper engagements with information and new media technologies. The Afrofuturist aspects of Ra, Coltrane and others’ work—their use of science, technology, and science-fictional media—inspire me (as a scholar and artist) to go into areas that, historically, have been inaccessible to black Americans and other marginalized ethnic groups. Like Sun Ra, my work remixes audio, video, images, and augmented reality projects that are driven by Afrofuturist production. This includes cosmographic art that, according to Amiri Baraka, can be touched, heard, or carried like a constantly communicating charm. These works serve as guideposts for black creative expression in the future that show black people ways to keep in or beyond the pace of society.