British antivirus company AVG offers many of its products for free. That’s Internet-speak for not free, but not directly paid for with money. A new iteration of the company’s privacy policy spells out more clearly what types of user data it collects and explains that it reserves the right to sell this data for actual money. It’s an arrangement that would sound more familiar coming from a social network than a cybersecurity company, yet here we are.

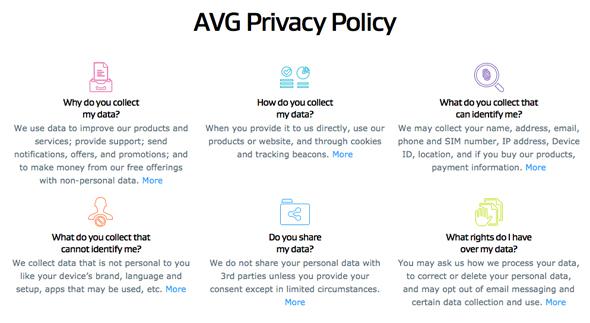

The terms of service seem straightforward at first. AVG says that it wants its products to act as reliable cybersecurity tools, and the company collects some user data so it can offer things like customer support and promotions. But it also aggregates data “to make money from our free offerings so that we can continue to offer them for free.” The document explains, “We use data that does not identify you, called non-personal data, for lots of purposes, including to improve our products and services and to help keep our free offerings free.”

AVG seems to want things like search queries, anonymized location data, and browsing history, but don’t worry! “You can be assured that we protect the information we collect.” We’ve all heard that before. An AVG representatives told Wired:

Those users who do not want us to use non-personal data in this way will be able to turn it off, without any decrease in the functionality our apps will provide. … While AVG has not utilised data models to date, we may, in the future, provided that it is anonymous, non-personal data, and we are confident that our users have sufficient information and control to make an informed choice.

The situation is concerning, though, because customers looking for a cybersecurity solution may not in fact receive “sufficient information” to understand that a product marketed to help them protect their privacy might also be surveilling them. Essentially the same product that is protecting people from adware, spyware, and malware might be exactly that. And your anti-virus probably isn’t going to alert you about itself. This is one reason that cybersecurity professionals are often skeptical of anti-virus products.

AVG claims to have more than 200 million active users, so this is potentially a significant point. The situation is reminiscent of what happened when Lenovo pre-installed Superfish adware on millions of PCs. People trust that laptops come out of the box clean and only acquire malicious software later—they’re not thinking about what the device maker itself might be implanting.

Of the Superfish incident, David Auerbach wrote on Slate in February that Lenovo “betrayed its customers and sold out their security.” At least AVG is being more upfront about what it might do with user data, but that doesn’t mean the business model isn’t creepy.