In the aftermath of a massive lake-effect snowfall event in western New York state on Tuesday, it’s worth asking: Is climate change playing a role here? Because, I mean, come on. Seventy—seven zero—inches, people. And another huge round is forecast for Thursday, by the way. Buffalo deserves answers.

The short answer is: yes. Global warming is probably juicing lake-effect snows, and we’ve had the data to prove it for quite some time.

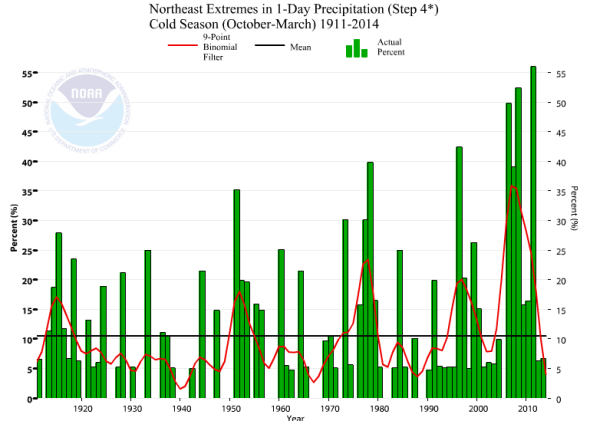

Courtesy of NOAA

Here are the details:

Truly extreme lake-effect snows gather their energy from a wide temperature differential between the lake temperature and the air temperature. That temperature contrast produces atmospheric instability—the warm air immediately over the lake wants to surge upward through the colder air on top, bringing with it heaps of evaporated moisture. That moisture is quickly converted to snowfall in massive quantities, and deposited squarely on the hills and towns at the far end of the lake. As the Great Lakes warm due to climate change, there’s now more evaporation, and more of an opportunity for that drastic water-air temperature difference to manifest itself, especially during the kinds of intense cold air outbreaks that we’ve been seeing seemingly more of over the last few years.

In Tuesday’s storm, that difference approached a whopping 50 degrees Fahrenheit—with a pool of warmer-than-average water in Lake Erie joining forces with near-record-low temperatures in the lower part of the atmosphere.

The result was a highly unstable atmosphere, in which thundersnow flourished and snow totals skyrocketed.

Another massive early-season lake-effect event occurred in Buffalo back in October 2006, when Lake Erie water temperatures were even warmer than they were this week. Almost a million people lost power.

Lake Erie is warming (along with the rest of the planet) by a steady but measurable amount. Since 1960 that trend has been about a half of a degree Fahrenheit per decade. More important than this, though, Lake Erie has been losing its ability to freeze over in the winter, with a decline of about one sub-freezing day per year in recent decades.

Courtesy of the EPA

In places such as Syracuse (downwind of Lake Ontario) and Buffalo, for the time being, that’s translated into more total snow each year. But it won’t always be this way. Several decades from now, the warming part of global warming will catch up, and total snowfall should begin a permanent decline. But for now, extreme snowfall events are winning out.

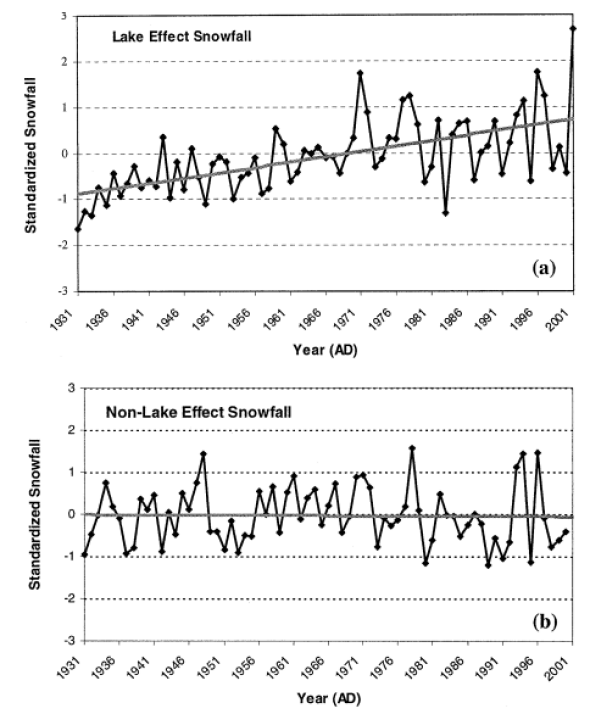

During our lifetimes, that means big lake-effect snowfall events like Tuesday’s are becoming more common, at least as a fraction of total snowfall. A 2003 study that used oxygen isotopes to distinguish local lake-effect snow from snow formed outside the region showed a sharp increase in lake-effect events over the last few decades. Follow-up research, including this study published last year, generally supports this conclusion.

Courtesy of Burnett, et al.

Earlier this year, New York state updated its assessment of statewide climate change impacts, essentially giving a forecast of the future of lake-effect snowfall in the state:

Annual ice cover has decreased 71 percent on the Great Lakes since 1973; models suggest this decrease will lead to increased lake-effect snow in the next couple of decades through greater moisture availability (Burnett et al. 2003). By mid-century, lake-effect snow will generally decrease as temperatures below freezing become less frequent (Kunkel et al. 2002). The high ice extent of the 2013-2014 winter highlights the fact that natural variability is expected to continue, even as long-term trends gradually shift the statistics in favor of low-ice winters.

All this is to say, if Slate suddenly transferred me to the Buffalo bureau, I’d be investing in a snow-blower.