The design of software underpins almost every facet of the way we live now, from the interactive bus timetable on your smartphone to the Excel spreadsheet you use at work, but design museums like the Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt in New York are struggling to find ways to preserve it.

While the museum owns tangible examples of America’s technological design history, an app named Planetary is its first foray into the world of digital design that has no physical form. It has, in fact, collected its first piece of living code.

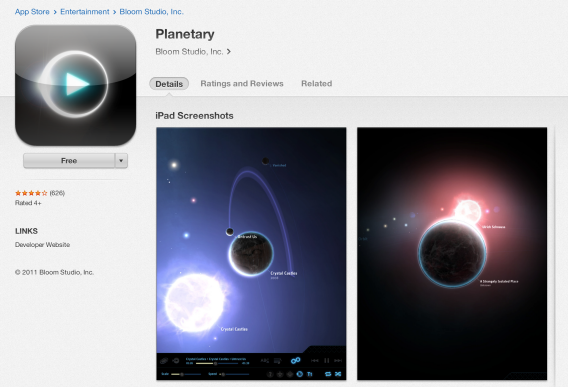

Planetary is an iPad app created by San Francisco startup Bloom in 2011. The app visualizes a user’s iTunes library as a 3-D galaxy of planets, stars, and moons. The interactive celestial objects each represent an artist, album, and individual songs, all in an immersive, logical flow.

But rather than keeping the original software on a shelf in its archive, the Cooper-Hewitt is trying something new: The museum is making the underlying code publicly accessible for download. It’s hoping that enterprising coders will use it to display other sets of data on new platforms in endless design iterations. It’s also hoping that the code will eventually be used to visualize the Cooper-Hewitt’s own vast collection.

By documenting the code’s design process and releasing images, screenshots, notes, and drafts that were made during the creation of the software, the museum is trying to take a snapshot of the way America designs now. “The impetus for the acquisition is that software has become one of the most significant arenas of design,” Sebastian Chan, Cooper-Hewitt’s director of digital and emerging media, told Clive Thompson in Smithsonian magazine.

The Planetary app is one way Cooper-Hewitt and many of its museum counterparts are experimenting with how best to preserve our most significant examples of digital design while addressing the challenges of rapid technological obsolescence. The Museum of Modern Art in New York is collecting video games like Pac-Man and The Sims, but they’re also contending with the issues of collecting and interacting with software that was developed on obsolete computers. While the Doomsday Book, written on sheepskin in 1086, is still well-preserved and readable at the U.K.’s National Archives, the BBC’s project of the same name was an ironic failure: They recorded information about the state of Britain in 1986 on two 12-inch videodisks—technology that became almost immediately obsolete and was accessible in 2000 by only the rare hobbyist with a surviving laser-disk player. Even Bloom, the startup that created Planetary, no longer exists.

Projects like Keeping Emulation Environments Portable, or KEEP, are one emerging option for design historians. KEEP is an emulation service that attempts to future-proof digital design environments so that long-term access is guaranteed. Olive, a similar collaboration between IBM and Carnegie Mellon University, proposes to archive the digital environments of the codes that produce software, games, and simulations, so that the code and its result is easily replicable in contemporary browsers.

But just in case, Cooper-Hewitt is also printing out the Planetary code on paper.