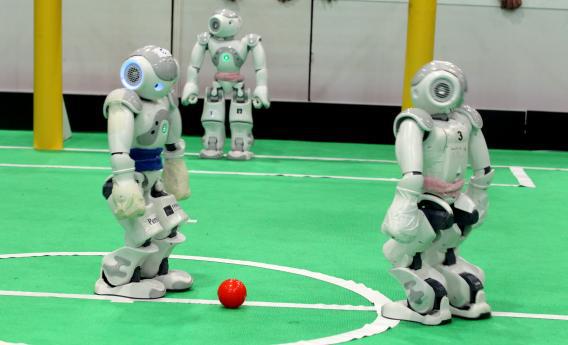

Scientists dream of building soccer robots good enough to compete against a World Cup-winning human team by the year 2050. If that target doesn’t strike you as ambitious, you clearly haven’t seen the hilarious exercise in ineptitude that is robot soccer today.

But if a Brazilian scientist at Duke University has its way, we could see a different kind of robotic soccer kick at the World Cup as soon as 2014. In Scientific American, Miguel Nicolelis proposes to outfit a paralyzed teenager with a robotic body suit—a sort of artificial exoskeleton. Controlling his mechanized limbs with his brain waves, the teen will walk out onto the pitch for the ceremonial first kick.

Then, on approaching the ball, the kicker will visualize placing a foot in contact with it. Three hundred milliseconds later brain signals will instruct the exoskeleton’s robotic foot to hook under the leather sphere, Brazilian style, and boot it aloft.

Nicolelis admits that his team, which includes collaborators in Germany and Brzail, will have to surmount “still formidable challenges” to make this a reality. Some of these challenges are technological. His team has succeeded in using a monkey’s brain waves to make two mechanical legs walk, but has not yet pulled off the more complex feat of helping a human paraplegic to boot a soccer ball. Other challenges are bureaucratic. The idea of a robotic first kick has won tentative support from the Brazilian government, but would still require approval from FIFA, the sport’s governing body.

If it doesn’t happen in 2014, though, Nicolelis hopes it will in 2016, at the Paralympic games in Rio de Janeiro. (The dazzling, bizarre opening ceremony of this year’s Paralympics made clear the games’ support for human enhancement.) And soccer aside, Nicolelis writes, these types of technologies will have plenty of real-world impact:

We are on our way, perhaps by the next decade, to technology that links the brain with mechanical, electronic or virtual machines. This development will restore mobility, not only to accident and war victims but also to patients with ALS (also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease), Parkinson’s and other disorders that disrupt motor behaviors that impede arm reaching, hand grasping, locomotion and speech production.

And the non-paralyzed needn’t feel left out. Nicolelis says similar technologies could augment healthy humans’ sensory and motor skills as well. If he’s right, it could be even harder for robots to beat humans in soccer by 2050—because the humans will be partially robotic too.