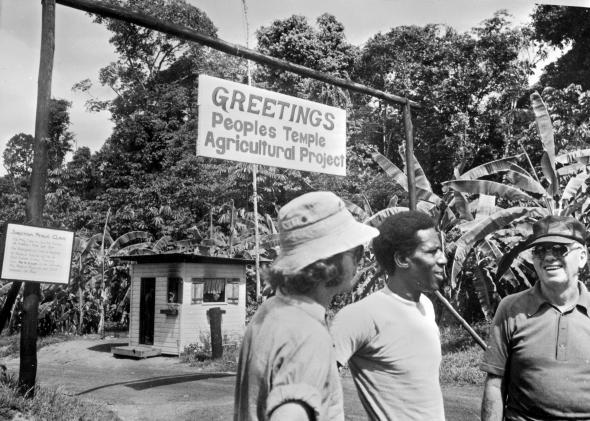

On Nov. 18, 1978, 35 years ago today, more than 900 people died after drinking poison at a failed utopian settlement in Guyana, in an incident that has come to be known as the Jonestown massacre. The deceased were followers of a deranged cult leader named Jim Jones, who had led his followers to Jonestown with promises of a better life, and had kept them there through violence and intimidation. In her 2011 book about Jonestown, A Thousand Lives, Julia Scheeres argued convincingly that Jones compelled the settlers to drink the poisoned beverage, and that the Jonestown massacre was not a case of mass suicide, but mass murder.

Jones probably would have poisoned his followers at one point or another anyway—People’s Temple defectors had reported that Jones had led his followers through mass-suicide rehearsals. But the incident was likely hastened by the unwelcome visit of a U.S. congressman, Leo Ryan, who had come to Jonestown the day before the massacre to investigate rumors that people were being held there against their will. The Jonestown poisonings still loom large in national memory—for one thing, that’s where we got the expression “drinking the Kool-Aid” (though packets of both Kool-Aid and a rival brand, Flavor Aid, were reportedly found at the scene.) However, relatively few people remember that Rep. Ryan was killed that day, too, shot dead on a Guyanese airstrip by Jones’ followers in an insane attempt to silence him. Thirty-five years later, Ryan remains the only U.S. representative to be killed in the line of duty.

Leo Ryan was a liberal legislator from northern California who had become famous for what his supporters called fact-finding missions and his detractors called publicity stunts. As a California state assemblyman, Ryan briefly worked as a substitute teacher in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles after the riots there, as a way to check on the state of the local schools. In 1970, while serving on a prison reform committee, he adopted a pseudonym and got himself locked up in Folsom Prison for 10 days. So it was within character when Ryan decided to visit Jonestown in 1978. In a letter to the chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee requesting permission to visit Guyana, Ryan wrote:

It has come to my attention that a community of some 1,400 Americans are presently living in Guyana under somewhat bizarre conditions. There is conflicting information regarding whether or not the U.S. citizens are being held there against their will. If you agree, I would like to travel to Guyana during the week of November 12-18 to review the situation first-hand.

Approval was given, and Ryan left for Guyana on Nov. 14, 1978, accompanied by two congressional staffers, nine journalists, and 18 relatives of Jonestown residents. Though the State Department had said that the trip was unlikely to be dangerous, Ryan’s staffers felt differently; before leaving for Guyana, one of them, Jackie Speier, took the time to make out her last will and testament.

The delegation first landed in Georgetown, the capital of Guyana. For a while, it seemed like they might not get any farther than that. Suspicious of the visitors’ intentions and anxious to prevent them from learning about the settlement’s dire conditions, Jones and People’s Temple officials would not initially allow the delegation to visit Jonestown. After a couple days of stalling, Ryan announced that he was chartering a flight to Jonestown, whether or not he was welcome. Jones finally relented, and allowed Ryan, his colleagues, and several media members and relatives to enter the settlement.

They arrived on Nov. 17, and were treated to dinner and some music as part of Jones’ attempt to convince the delegation that all was well in Jonestown. The illusion was unconvincing: Throughout that night, the visitors were approached by Jonestown residents “seeking protection and a way out of their tropical nightmare,” as Speier would later write in a piece for the San Francisco Chronicle. When the Ryan group departed Jonestown the next day, they were accompanied by approximately 15 defectors, and were making plans to go back for more. Jones’ attempt to deceive the visitors had failed. It was time for his backup plan: killing the messengers.

On the afternoon of Nov. 18, the group headed for the Port Kaituma airstrip, where two planes had been chartered. Around 5:20 p.m., as a plane filled with defectors was about to take off, one of the passengers—Larry Layton, a Jones loyalist posing as a defector—pulled a gun and started shooting. “I heard screams and the unfamiliar sound of gunshots as, inside one of the aircraft, Layton opened fire,” Speier later wrote. Speier, Ryan, and several others were standing on the airstrip at the time, waiting to board another, larger plane. They didn’t get the chance.

“Within seconds, gunmen leaped from a nearby tractor and leveled their weapons at us,” Speier wrote. “I dived to the ground behind an airplane wheel and pretended to be dead.” Speier survived. Ryan, a defector named Patricia Parks, and three journalists—NBC reporter Don Harris, NBC photographer Bob Brown, and San Francisco Examiner photographer Greg Robinson—were killed. This happened around 5:20 p.m. Twenty minutes earlier, the settlers had begun taking poison back in Jonestown.

The 900-some poisonings became the story, understandably, and the deaths of Leo Ryan and the other shooting victims were overshadowed. But the congressman was not entirely forgotten. Five years later, President Ronald Reagan gave Ryan the Congressional Gold Medal. Thirty years later, his staffer, Jackie Speier, was elected to Ryan’s old congressional seat. She said that her old boss remained an inspiration.