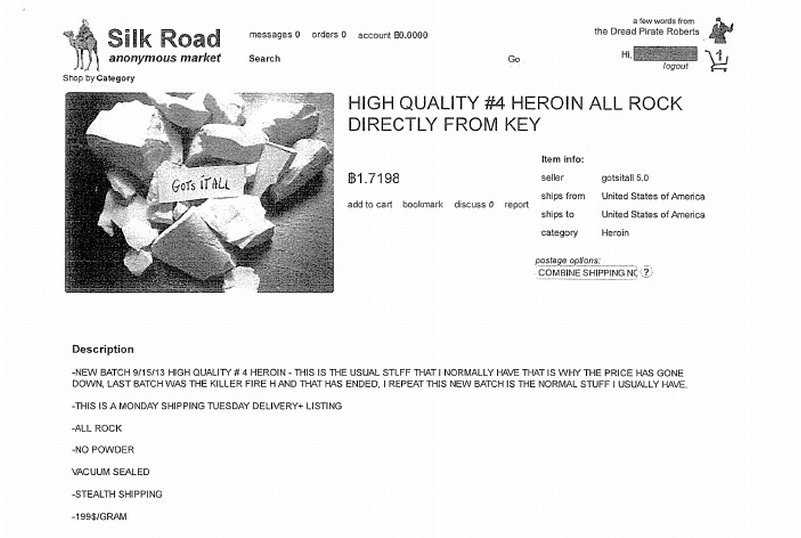

Silk Road, a prominent online marketplace for illegal goods and services, has been seized and shuttered by the FBI, and its alleged proprietor arrested. Ross William Ulbricht, a 29-year-old San Francisco resident who went by the name “Dread Pirate Roberts,” was charged with operating a site that made buying illegal drugs almost as easy as ordering a book from Amazon. The criminal complaint against Ulbricht called Silk Road “the most sophisticated and extensive criminal marketplace on the Internet today,” which sounds about right, given that the site was a clearinghouse for drugs, fake IDs, and other things you can’t buy at Walmart. The site was accessible only by Tor, an anonymizing network that helps facilitate secure online communications; all business was transacted in Bitcoin, the relatively anonymous online currency, thus providing Silk Road’s users another level of security.

In a major story for Forbes earlier this year, Andy Greenberg characterized Dread Pirate Roberts as “a radical libertarian revolutionary carving out an anarchic digital space beyond the reach of the taxation and regulatory powers of the state—Julian Assange with a hypodermic needle.” (The story also estimated that Silk Road saw about 60,000 visitors per day and did about $30 million to $45 million in annual revenue.) The criminal complaint against Ulbricht, which is worth reading in full, makes the case that, revolutionary or otherwise, he was a fellow who didn’t do a great job covering his tracks.

The complaint alleges that not only did Ulbricht manage and maintain a site that facilitated more than $1.2 billion worth of mostly illegal transactions in its two and a half years of operation, he also solicited a hit man to murder someone who was threatening to reveal the names of several thousand Silk Road users. (While Ulbricht apparently paid the assassin, the FBI can find no evidence that the hit ever took place.) The feds caught Ulbricht’s scent after Canadian authorities randomly intercepted a package of fake IDs that was en route to Ulbricht’s San Francisco address. From there, they were able to accumulate enough circumstantial evidence to convince them that Ulbricht was Dread Pirate Roberts.

The government has been after Silk Road for a while, and it’s interesting to note that the site was brought down not by some great feat of hacking, but by old-fashioned investigative work. The idea behind Silk Road was that, if you followed the proper security protocols, you could conduct illegal transactions right out in the open and the government would be powerless to stop them. As far as I can tell, nothing in the criminal complaint disproves this notion. Ulbricht was arrested not because Tor failed, but because it is risky to send illegal goods through the mail. Further, agents were able to corroborate their suspicion that Ulbricht was Dread Pirate Roberts not by defeating Tor, but by noting that some of the earliest message board postings touting Silk Road were linked to an email address in Ulbricht’s name. And as Slate’s Will Oremus already reported, the criminal complaint also indicates that Ulbricht stupidly used his real name to ask an in-retrospect-suspicious question on an online coding forum. The security failures here were human, not technological.

You read a lot these days about how online privacy doesn’t really exist, and how the government can crack most encryptions. And while this is undoubtedly true, the best online privacy measures are still pretty good—or, at least, good enough to stymie the FBI. Silk Road isn’t the only black-market website out there, and if the others ever get busted, I’m guessing it’ll be thanks to a similar human slip-up.